Mike Leigh on Hard Truths, Losing Dick Pope, and the Duty of an Artist

The British cinema––indeed an entire strand of understanding around modern drama––does not exist without Mike Leigh. When it was learned some years ago that Leigh was struggling to obtain financing for a new film, the outrage among cineastes was commensurate with little else, I think in large part for how much he alone represents the […] The post Mike Leigh on Hard Truths, Losing Dick Pope, and the Duty of an Artist first appeared on The Film Stage.

The British cinema––indeed an entire strand of understanding around modern drama––does not exist without Mike Leigh. When it was learned some years ago that Leigh was struggling to obtain financing for a new film, the outrage among cineastes was commensurate with little else, I think in large part for how much he alone represents the fabled, ever-threatened “movies for adults,” to say nothing of how distinctly they’re created, how distinct their effects.

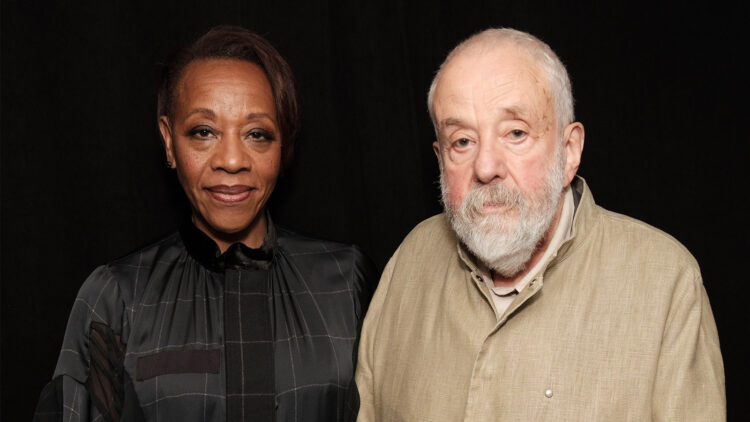

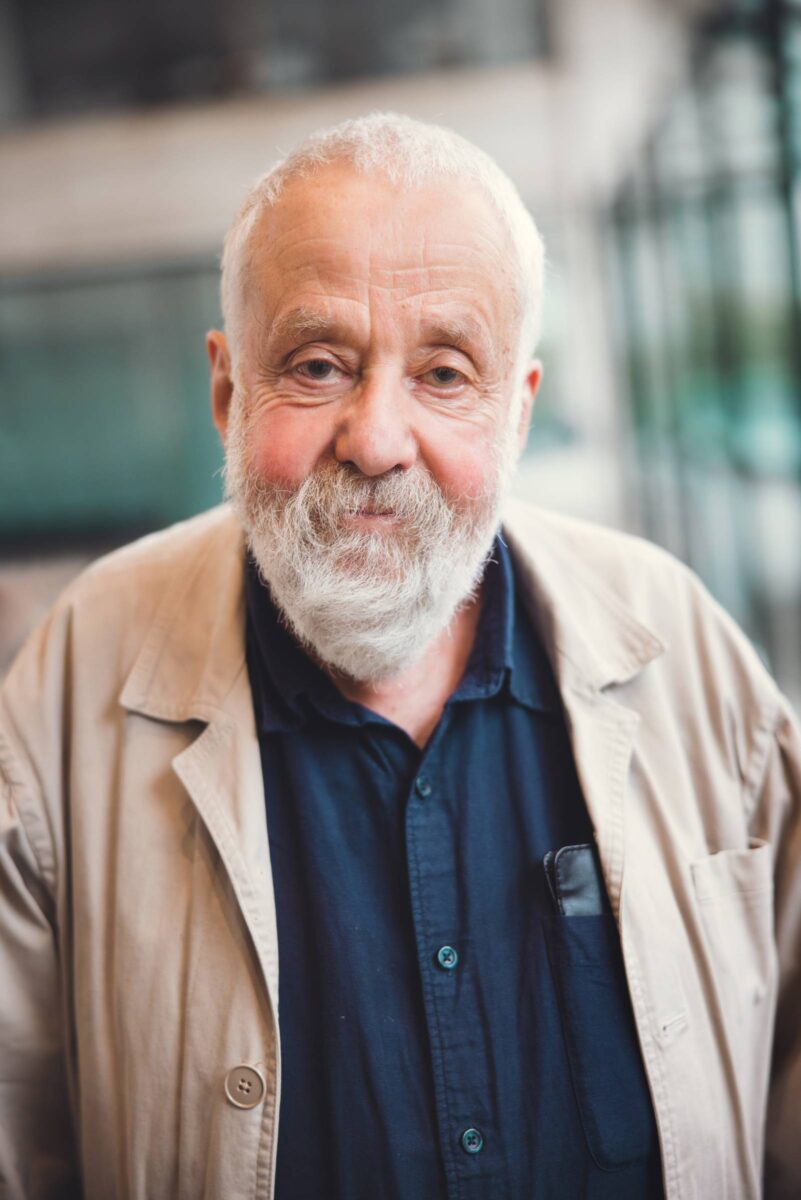

There’s thus an occasion around today’s release of Hard Truths, which debuted on the fall-festival circuit and receives a proper opening after last month’s Oscar-qualifying run. Leigh was in town to present both the film and Marianne Jean-Baptiste’s deserved win for Best Actress at this year’s NYFCC gala. Meeting in a large, sterile hotel room the likes of which aren’t often seen in his films, we sat to discuss Hard Truths, his recently departed cinematographer Dick Pope, and an artist’s duties. Even (or especially) when Leigh found a question worth contending, he made an invigoration conversation partner.

The Film Stage: Surely you don’t remember this, but we had met several years ago in an elevator at Cameraimage. I had in my hand a copy of Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night.

Mike Leigh: Oh, yeah.

And you got very excited about what a great book it is, fitting all these enthusiasm about Céline into like the eight seconds that we were in the elevator together. I’ve always cherished that experience.

I mean, he’s fascinating, isn’t he? Because he was a terrible fascist. And yet what he writes is so compulsive, isn’t it? Yeah, it’s interesting––you know, speaking as a non-fascist. [Laughs] As one does. Interesting. I’d forgotten that but now you remind me.

I also had talked to Dick Pope at that festival––the second time I had spoken to him––and though I wouldn’t say I knew him, I was very sad about his passing.

Terrible. Devastating. He was very ill, and indeed he shot Hard Truths, but for the first time and only time he didn’t operate the camera himself. You know, he did it in the other room with a monitor and our long-time colleague, Lucy Bristow, operated. But the good news––for what it’s worth––is that he knew the film was being successful just before he died. But it’s tragic, really.

This film in particular really got to me, and I think part of why is that you’ve put onscreen certain family dynamics that I don’t see represented in film a lot.

Sure.

In particular, the dynamic of a kind of overbearing, oppressive adult and their long-put-upon spouse and the child who suffers from that. It’s something that I’ve seen a lot in my own life; it’s unbearable to be around for five seconds. And there are certain moments in Hard Truths that felt so one-to-one with things I’ve seen––even like the ways people decide to sit in rooms and not look at each other––and I’m wondering if there were particular dynamics that you’ve observed in people in those sorts of domestic settings that you were kind of pulling from for this?

Yeah. I mean, it’s not a straightforward thing to answer. What I haven’t done in any identifiable way is to draw consciously and specifically from actual sources or experiences. Having said that: of course, what you’re talking about––what’s in the film––absolutely resonates with experiences that people and stuff I’ve known about. But I didn’t think at any point, consciously, “This is X, Y, or Z.” You know. I suppose it’s a hard question to answer in a sort of easily black-and-white term. Because I make the work in most of the films––which is to say probably, apart from the historical ones that I’ve made––because I unearth what it’s about through the process of actually doing it, the way other artists in other media do; I tap into a whole bunch of ongoing preoccupations and ideas and experiences and so on in a… not an unconscious way, but I suppose a subconscious way. The short answer to your question is: it’s not a direct portrait of anybody in particular, but it resonates with all sorts of experiences and people.

That kind of leads into something I’ve been wanting to ask ever since I saw the film, or a thought that occurred to me watching the film. A decade ago, a good friend interviewed you about Mr. Turner. He asked if you saw yourself in J.M.W. Turner, and your response to that question has long stuck with me.

What?

“That’s a fairly silly question.”

[Laughs] Well, I don’t know why I said that. It’s not a silly question.

I don’t want to repeat that mistake by asking yet another fairly silly question, but I had to wonder how much of Pansy’s attitudes could stem from your own lived feelings, real reactions, even if––to us, the viewer––we can assume this place of superiority.

[Laughs] I would have to say, that compared with asking me about whether I thought myself as J.M.W. Turner, that is a sillier question.

Great.

No. The answer is no, actually. It’s not for me to celebrate myself, but I’m a pretty compassionate, good-humored, generous, etc., etc. kind of person. If I wasn’t, I couldn’t do what I do apart from anything else. In fact, by this time, even in this conversation, you’d have had a hard time with it, really, if I was a Pansy. But, you know, to be serious about this––if we have to be––it’s kind of not really… I don’t really know what the question is about or where it comes from. As an observer of life, of people––as an artist, as a distiller of what I see into coherent, dramatic, cinematic, digestible form––an artist has to be, whilst at the same time compassionate and motivated by his or her feelings, objective and, you know, look at everybody clearly.

[Pause] I actually don’t know, in real terms, how one would make a “self-portrait,” or whatever you call it, with the kind of integrity and… see, it’s a combination, isn’t it, of what us, we artists do. We are depicters of humanity. It’s a combination of being of objective detachment and an emotional empathy and all of that. Apart from storytelling and all the rest of it. So that’s trying to deal with what you’re asking me as comprehensively as I can, but on the whole, it’s not really… the proposition of what you and your colleague are asking me, it’s kind of not really relevant, strictly speaking.

To go back to what you said, the thought of asking something like that: I think partly it’s because I felt like I understand the character very well in terms of… I’ve never blown up at a stranger the way that she does.

No.

But I have had those internal monologues. And I’ve had the moments where I feel like I’m starting to crack up.

Make no mistake: we all have. I lose it sometimes. Of course. Apart from anything else, I’ve been married, divorced, I’ve been in relationships, and I’ve got two adult sons. So yeah. [Laughs] I’ve lost my fuse––my rag, whatever you call it. Of course one does. But that’s not behaving like Pansy. That doesn’t come from a running condition, such as she does. Yeah, I don’t know how to say it, but we’ve kind of… I think we’ve talked about this, really.

Sure.

I think the one thing I really want to stress is that it’s the complexity and the––how do I put it without being pompous?––duty of an artist is to be objective and detached and compassionate and subjective.

Photo by Arin Sang-urai, courtesy of Film at Lincoln Center

This is your first contemporary film since Another Year from 2010, and I think it’s fair to say that the world has changed a lot in the last 14 years. When I talk to filmmakers, they say they have something of a hard time depicting the modern world because people are just constantly, you know, doing [Picks up and looks at phone] this.

Yeah.

And I thought it was interesting in the film how there’s not such a preponderance of screens or devices.

[Laughs] Well, actually, the only time in any of my previous films you see an early version of a mobile telephone is in Naked, where the landlord character’s got what, at that time, was called a field phone––which is about [Expands hands] this big––in his car. Here it figures when Chantelle calls her and she’s in the supermarket. I’m conscious of that. [Pause] I haven’t had to work really at all hard to avoid that because, you know, it’s about people communicating in all the ways that human beings communicate. I haven’t had to sort of deliberately avoid it. But I’m aware of it. I mean, it’s interesting. What you’re actually talking about on a sort of, I suppose, more fundamental level… I mean, people have said about this film, “Oh, well, it’s obviously post-COVID.”

Right.

“Obviously, you know, this is a result.” Well, I never thought about that and I don’t really see it as such. It is post-COVID because it’s plainly set in the 2020s and that, by definition, is post-COVID. COVID is referred to about one-and-a-half times in the film in passing. But in terms of what the film is actually about––I’m sure you will agree––we could have made the film 10, 20 or 30 years ago.

Of course.

In terms of what it’s actually about, basically. And to me that’s the bottom line––the long and the short of it––quite frankly. So yeah: of course it’s from the world that was extant in 2010. In all kinds of ways, sure, the world has changed, but at the same time it’s constantly, consistently the way human beings are. And as an aside to what we’re talking about: the interesting thing about having made three actual period films––four, actually, including Vera Drake, which is set in 1950. Or even four-and-a-half. Have you seen Career Girls?

I have.

Where, plainly, we’re looking at the mid-90s and mid-80s at the same time. But just to stick to the Victorian film, the 19th-century films: obviously we’ve gone to great lengths and bent over backwards to research and be as accurate as possible within the limitations of the fact that we are 20th- and 21st-century filmmakers. In the end, the reason why I was able to do that was because people are people and society is society, and the mechanics of things––the surface stuff––is transitory, really. Transient.

Moses playing with his flight simulator––I think it’s interesting that that’s one of the only times in the film we see a character kind of locked into a device.

A device. Apart from the mobiles, the cells.

I wanted to ask about having Lucy Bristow move from B operator, which she had done on some previous films, to main operator, and how you found that transition.

We didn’t even think about it because we were, three of us, communicating as one. I mean, Dick communicates with her and with me and it was very natural, you know. It isn’t absolutely the first time I’ve worked with two people doing it––in the past, long ago––but no, I mean, we’re all on the same wavelength. There’s not a lot I can say about that. Because Dick, his input would be as important as hers and mine; we simply were in a harmonious tandem, really.

I certainly don’t see Hard Truths as having a different visual character.

Yeah. I mean, once you get into it, that’s what we’re doing. And I didn’t keep thinking, “Oh, Dick isn’t doing this.” [Laughs] And also, she worked as a trainee on High Hopes. Which we made a long time ago, which was shot by Roger Pratt––who’s a great cinematographer who also died on the 1st of January. At exactly the same age as Dick Pope, strangely enough. So we’ve known each other a long time. She’s been on. And, as you obviously know, she always comes in if we need a second camera, which is not very often. She’s been a focus-puller.

You’ve said said that you have ambitions to make more films.

I’m going to make another film this next year, yeah.

Obviously I understand if it’s far too soon to be asking this, but I think people see you and Pope as so analogous, working so beautifully together. Do you have any sense of who would be its cinematographer?

No, we’re looking at it. Can’t say anything about that. It’s under investigation. One thing is certain, beyond dispute: that one person who would be appalled if I said, “Oh, well, without Dick Pope I’m not going to make another film” is Dick Pope. He would be up there [Points up] or [Points down] down there, wherever he is, extremely pissed off about it.

Having met him a couple of times, I’ll guess he’s up.

Well, having met him more times than you have, he might be down there. But I jest.

I won’t investigate.

No, no.

I would love to know what the new film is, but if you don’t even tell financiers…

I really don’t; I can’t. Not only won’t I, but I can’t because, until it’s absolutely in place, I’ve always got lots of ideas. So yeah. It’ll be a contemporary film––that I can tell you. I think.

When I had talked to him about Peterloo at Camerimage years ago, he said something that I thought was really interesting: “Sometimes it’s good to create ugly light.” Which is an ethos––inasmuch as it is an ethos––that I love. And I thought about that when I was watching Hard Truths because it’s not set in particularly attractive spaces. Not terrible spaces, but: suburban homes, supermarkets, doctor’s offices. And I wonder what some of the thinking is with photographing the quotidian, making it interesting. Are they inherently compelling to you, or is it about finding something?

This is a funny question. Everywhere is interesting. I mean, people say, “Oh, I make films about people.” Sure. But to me, place is fascinating. When I was an art student, life drawing was very important; I learned a lot in the life drawing class. Nude model or an old guy with old clothes on and then we’d all sit around. But on Saturdays, we used to go out and about around London drawing buildings. That’s what it was about. A great old guy would be the tutor and we’d go and look at all kinds of buildings. You know, I’m a great fan of Vermeer, for example, and so was Dick Pope. And I grew up in Manchester, in an ordinary middle-class home; I lived in a working-class area because my dad was a doctor. I went to school with working-class kids, mostly. I was in and out of other people’s homes. To me, exterior is interior is place. Places that people live. That is the substance of life, you know. Exotic buildings are as interesting and… I mean, I’ve been to Venice a few times. It’s fascinating, but it’s no more or less fascinating than an ordinary suburban living room.

So I don’t really… everywhere, it’s got its own character and it’s interesting to me and is a subject matter. So it’s interesting, what you say, because I don’t really… I mean, obviously, at another level––we’re talking now at a different level––in this film, in Hard Truths, plainly, there’s something very specific about Pansy’s house, which is a function of the character. She’s obsessively sterile. I mean, when I said to Suzie Davies, the production designer, that she would have white carpets, Suzie Davies said, “Oh, but they get dirty.” And Marianne will tell you, her answer was, “Not Pansy’s carpets.” But that in itself is imagery. That is character. That sterile house is character––something that therefore is, for me, interesting in its own right. Just as the parallel pad of Chantelle and her daughters, which is full of life and stuff, flowers on the balcony and all the rest of it. So what I’m saying, obviously, is: it doesn’t matter where it is. Place has character. I’ve never… I don’t remember talking with Dick, hearing Dick talk about “ugly light” as such. I think what he must mean––obviously, when I think about it––is light that is… not sugaring the pill.

Sure.

Light that sexes it up. In other words, he means “honest light” rather than “ugly light” as such. He has never really had the ability to make things ugly. It’s to not sugar the pill.

I like that you mentioned Vermeer; I’ve long remembered Pople telling me that if you have a woman by a window with the light coming in and you set up a camera, “we can all be Vermeers.” That sentiment has stuck with me for a long time.

Yeah. Yeah. My first film, Bleak Moments––he didn’t shoot that. It was shot by somebody else a long time ago. But again: Vermeer was in our minds back then, when we were in our 20s.

I was surprised, looking at the film again, how many of the spaces I had specifically remembered for months. Because I saw it in October.

Yeah.

Chantelle’s apartment in particular, I was surprised at how much I had remembered that. And the little… not the staircase, but the outer entrance to the apartment as well.

I mean, that’s good. Because again, here’s the thing: in dramatizing––in rendering into cinematic terms––the characters and their environment, hopefully one is distilling it to a concentrated image. I mean, that’s what a film should do, obviously. But obviously, of course––I suppose; this is not for me to say––but you’re talking about these things because in some way, implicitly, it means that not all movies do this.

No, they don’t.

But then, not all movies are concerned with depicting real life. To put it as plainly. And that’s all I’m concerned with, really, is distilling real life and having something to say about it. I mean––of course, it goes without saying––a lot of films are movies about movies; I do not make movies about movies. In fact, funnily enough, I’ve been asked quite a few times, in the context of this film, whether I was thinking about other films––particularly Happy-Go-Lucky––while I was making it. “Is this the flip-side of Happy-Go-Lucky?” I mean––that’s bullshit, quite frankly. I’ve never thought about another film of mine––or indeed anybody else’s film––while I’m making a film; I’m thinking about what it’s about and the world we’re depicting. I think that’s got something to do with what you’re talking about.

It might. I mean, I probably remember a stranger’s home that I entered five months ago better than the location from a movie I saw last month. Because it is a place that the person is defined.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

This five-star hotel is not a defined place.

Well, you say that––and I see what you mean, and I don’t actually disagree with you as such––but, and indeed, I’m staying in a room on another floor, and that’s got that same picture. [Points to black-and-white photo of woman’s face on the wall, laughs] Which in itself is remarkable. That’s in the bedroom, obviously, and that means that some lonely businessmen can gaze at that and have a good old wank. It’s fairly outrageous, really. But the point is this: if I were making a film about this room and the characters in it, it would become as interesting as an “interesting” room. Because we’d be looking at it in terms of expressing what it is.

I trust that you would make it interesting.

Well, interesting within the context of whatever… you know. Depends on your definition of “interesting.” [Laughs] But what I’m saying: it doesn’t not qualify as a place, because it is a place and it’s been made by human beings, and it’s, in a particular way, inhabited by human beings.

I had found this quote that you gave about 10 years ago, where you said, “I’ve never made a film where I didn’t think, ‘This is the one. This is the disaster.’” Did you have that feeling before this film?

I don’t think so.

Oh.

I don’t even know what I’ve said is true. [Laughs] I think you should take it with a pinch of salt. Well, I mean, I will say this in the context of the question: we finished the film November before last. And immediately the French distributors said, “Oh, this is a shoo-in for Cannes.” So they made us finish the subtitles––I always work with this guy in Paris––by Christmas before last. Because they wanted to show it to Cannes before Christmas. They did; Cannes turned it down. Then they showed it to Cannes again, and they repeated that they didn’t want it. And the French distributors were outraged and shocked. We were surprised, but there you go.

Then everybody said, “No, it’s okay, though. It’ll be in Venice.” So they showed it to Venice and Venice turned it down. And then, remarkably, Telluride turned it down. So by the end of half a year we then started to think, “Maybe we made a shit film.” Then Toronto saw it and they went wild. And everybody else who’s seen it since––including the festivals: Toronto, London, San Sebastián, New York at least––everyone loves it; it’s great. But that’s not really what you’re asking me. You’re asking me whether I felt it while making the film. Not really.

Just after.

Because nothing was happening. It wasn’t the feeling of self-doubt while making it. It was simply you think, “Hang on a minute. We thought this was…” I mean, I’ve had that experience before. We had it with Topsy-Turvy, for example; we had French backers who actually, literally came over to see it. We finished it and we thought we’d made a pretty good go of it, really––I think we did––and the French backers came over and said, “Zis is a terrible film! No way you’re going to Cannes. If you go to Cannes, the critics will eat you alive.” I quote verbatim what they said. So we took it to Venice and it was very successful. But you just don’t know. But we’re talking about two different things: you’re talking about me being insecure about the film while I’m making it; I’m talking about other people’s reactions.

Right. But one thing plays with another. Having seen a lot of the movies that played in competition at Cannes and Telluride, let’s just say there’s no accounting for taste if they would reject this film.

That’s a… yeah, that’s a reasonable thing for anyone to think. Including me. [Laughs] But you never know. Cannes turned down Peterloo. In a way, Peterloo was a tougher proposition for a lot of people; it’s hard to swallow, more obscure. But hey: we fight the fight.

It worked out. You get to sit face-to-face with me, taking both fairly silly questions and, hopefully, some good questions too.

No, not at all. Not at all. I mean, yeah, the questions are legitimate. But if I say, “Well, it’s not really relevant,” it’s because it sort of isn’t what it’s about.

But I’ve got to ask to find out.

No, it’s your prerogative, and indeed your duty. [Laughs] Very nice to see you; thank you. Have you now read the complete works of Céline?

I haven’t. That’s my fault.

It’s very readable, really. It’s extraordinary.

Do you like Death on the Installment Plan?

Yeah. That’s the first one I read.

Okay. That’s the next one I’ll read.

A mate of mine, who’s dead now and wrote a play, turned me onto him in the first place. He said, “You’ve got to read this.” And I was astonished by it; it’s great. I would not like to have met him, actually. He sounds like a reprehensible character. But hey. [Laughs] There you go.

Hard Truths is now in theaters.

The post Mike Leigh on Hard Truths, Losing Dick Pope, and the Duty of an Artist first appeared on The Film Stage.

What's Your Reaction?