The Artist Turning Bones Into Beautiful Dishware

Tableware has long played an important role in the dining experience. The color, shape, and design of plates and bowls not only impact the presentation of the food and diners’ perception of the meal, but they’re also an expression of the chef’s overall artistic vision. Blue Hill at Stone Barns in Pocantico Hills, New York, is lauded as much for its fine dining as it is for its sustainability practices.* Every aspect of the farm-to-table establishment showcases the relationship between agriculture and gastronomy—from chef Dan Barber’s commitment to locally sourced, seasonal organic ingredients right down to his dishware. More than a canvas for colorful vegetables and perfectly prepared proteins, each seemingly simple setting of plate, bowl, and water cup is the embodiment of Barber’s nose-to-tail philosophy. Handcrafted by Pennsylvania artist Gregg Moore, the dishware is made from the bones of Stone Barns’ own cows. “I think that more than the majority of people don’t realize that bone china is made with real bone,” Moore says. “They think maybe it’s describing the color, that it’s the same shade as bone, or that it has to do with the product’s fragility. But it’s not, and it’s kind of an ‘ah-ha’ moment when you realize that.” Moore, a professor of ceramic art at Arcadia University in the Philadelphia suburb of Glenside, first became interested in working with Barber after reading the chef’s book, The Third Plate: Field Notes on the Future of Food. The son of a butcher and an avid gardener, Moore often uses his work to explore the connection between agriculture and ceramics. “The recontextualization that I’m trying for is very much a story about how humans interact with the environment and our place within that,” he explains. “And where that takes place the most is at the dinner table.” Barber recalls his initial meeting with Moore. “Gregg introduced himself many years ago by suggesting something to me that was at once profound and also crazily obvious: Since I was obsessed with knowing where the food for my menu comes from, how it’s grown and raised, and all the elements that go into a dish, why was I overlooking the origins and materials of what the food at Blue Hill was served on?” he says. After the cow bones are stripped of their meat and marrow—when they no longer have any culinary applications—they are boiled at high temperatures to clean and prepare them for a two-step kiln-firing process. “[This process] takes what was a biological material, the bone, and turns it into a geological material, a mineral,” Moore explains. “Anything that’s carbon based—the fats, liquids, meat—burns away, and the only things that are left in a grass-fed bone are calcium and phosphorus.” The result is a stark white bone. At this point, Moore collects the bones and brings them to his studio where he mills them into a fine powder known as bone ash. He prefers femurs due to their density and the fact that they offer the most material after the process. Moore then adds the bone ash into a liquid clay base that he casts to make bone china. In order for a porcelain to be labeled as bone china, it must contain at least 30 percent bone ash. Moore uses a recipe developed in the late 1700s by Josiah Spode, founder of the eponymous houseware brand and the potter credited with inventing bone china as we know it today. “The bone china that I produce is nearly identical to the bone china that Spode made 250 years ago,” Moore says. Spode’s formulation—25 percent kaolin clay, 25 percent Cornish stone (a high-silica feldspar also known as Cornwall stone), and 50 percent bone ash—remains the standard, although the quality of the finished product varies depending on how the animals were raised. Since beginning the collaboration with Barber, Moore has researched how farming practices affect the quality of bone china. He and a university colleague secured a grant to study three sample sets of cows: grass-fed (Blue Hill has been serving 100 percent grass-fed beef since it opened 20 years ago), grain-fed, and industrially raised or CAFO (concentrated animal feeding operations) where animals are raised in confinement. The farmers they worked with tracked the animals’ diets, exercise, birth rates, and lactation cycles. The bone ash and resulting ceramics were scientifically analyzed for strength, whiteness, and translucency, the three criteria for which bone china is traditionally judged. Moore found that the bones of grass-fed cows are pure hydroxyapatite, a chemical compound of calcium and phosphorus that gives the bone, and thus the bone china, its whiteness and strength. The bones of the factory-farmed and grain-fed cows contained high levels of whitlockite, a marker of metabolic bone disease. This impurity results in bone china that is of lower quality: tinted yellow, less translucent, and more fragile.“The better you treat the animal, the more exercise it gets and access to grass, the better the bone china,” Moore says.

Tableware has long played an important role in the dining experience. The color, shape, and design of plates and bowls not only impact the presentation of the food and diners’ perception of the meal, but they’re also an expression of the chef’s overall artistic vision.

Blue Hill at Stone Barns in Pocantico Hills, New York, is lauded as much for its fine dining as it is for its sustainability practices.* Every aspect of the farm-to-table establishment showcases the relationship between agriculture and gastronomy—from chef Dan Barber’s commitment to locally sourced, seasonal organic ingredients right down to his dishware.

More than a canvas for colorful vegetables and perfectly prepared proteins, each seemingly simple setting of plate, bowl, and water cup is the embodiment of Barber’s nose-to-tail philosophy.

Handcrafted by Pennsylvania artist Gregg Moore, the dishware is made from the bones of Stone Barns’ own cows. “I think that more than the majority of people don’t realize that bone china is made with real bone,” Moore says. “They think maybe it’s describing the color, that it’s the same shade as bone, or that it has to do with the product’s fragility. But it’s not, and it’s kind of an ‘ah-ha’ moment when you realize that.”

Moore, a professor of ceramic art at Arcadia University in the Philadelphia suburb of Glenside, first became interested in working with Barber after reading the chef’s book, The Third Plate: Field Notes on the Future of Food. The son of a butcher and an avid gardener, Moore often uses his work to explore the connection between agriculture and ceramics.

“The recontextualization that I’m trying for is very much a story about how humans interact with the environment and our place within that,” he explains. “And where that takes place the most is at the dinner table.”

Barber recalls his initial meeting with Moore. “Gregg introduced himself many years ago by suggesting something to me that was at once profound and also crazily obvious: Since I was obsessed with knowing where the food for my menu comes from, how it’s grown and raised, and all the elements that go into a dish, why was I overlooking the origins and materials of what the food at Blue Hill was served on?” he says.

After the cow bones are stripped of their meat and marrow—when they no longer have any culinary applications—they are boiled at high temperatures to clean and prepare them for a two-step kiln-firing process.

“[This process] takes what was a biological material, the bone, and turns it into a geological material, a mineral,” Moore explains. “Anything that’s carbon based—the fats, liquids, meat—burns away, and the only things that are left in a grass-fed bone are calcium and phosphorus.” The result is a stark white bone.

At this point, Moore collects the bones and brings them to his studio where he mills them into a fine powder known as bone ash. He prefers femurs due to their density and the fact that they offer the most material after the process.

Moore then adds the bone ash into a liquid clay base that he casts to make bone china. In order for a porcelain to be labeled as bone china, it must contain at least 30 percent bone ash. Moore uses a recipe developed in the late 1700s by Josiah Spode, founder of the eponymous houseware brand and the potter credited with inventing bone china as we know it today.

“The bone china that I produce is nearly identical to the bone china that Spode made 250 years ago,” Moore says. Spode’s formulation—25 percent kaolin clay, 25 percent Cornish stone (a high-silica feldspar also known as Cornwall stone), and 50 percent bone ash—remains the standard, although the quality of the finished product varies depending on how the animals were raised.

Since beginning the collaboration with Barber, Moore has researched how farming practices affect the quality of bone china. He and a university colleague secured a grant to study three sample sets of cows: grass-fed (Blue Hill has been serving 100 percent grass-fed beef since it opened 20 years ago), grain-fed, and industrially raised or CAFO (concentrated animal feeding operations) where animals are raised in confinement. The farmers they worked with tracked the animals’ diets, exercise, birth rates, and lactation cycles.

The bone ash and resulting ceramics were scientifically analyzed for strength, whiteness, and translucency, the three criteria for which bone china is traditionally judged. Moore found that the bones of grass-fed cows are pure hydroxyapatite, a chemical compound of calcium and phosphorus that gives the bone, and thus the bone china, its whiteness and strength. The bones of the factory-farmed and grain-fed cows contained high levels of whitlockite, a marker of metabolic bone disease. This impurity results in bone china that is of lower quality: tinted yellow, less translucent, and more fragile.

“The better you treat the animal, the more exercise it gets and access to grass, the better the bone china,” Moore says.

“Chemically, my bone china has more in common with Spode’s than it does with contemporary bone china because we use grass-fed bones,” Moore adds. “The animals at Stone Barns are raised like they were back then, out in the fields where they’re walking around and eating grass.”

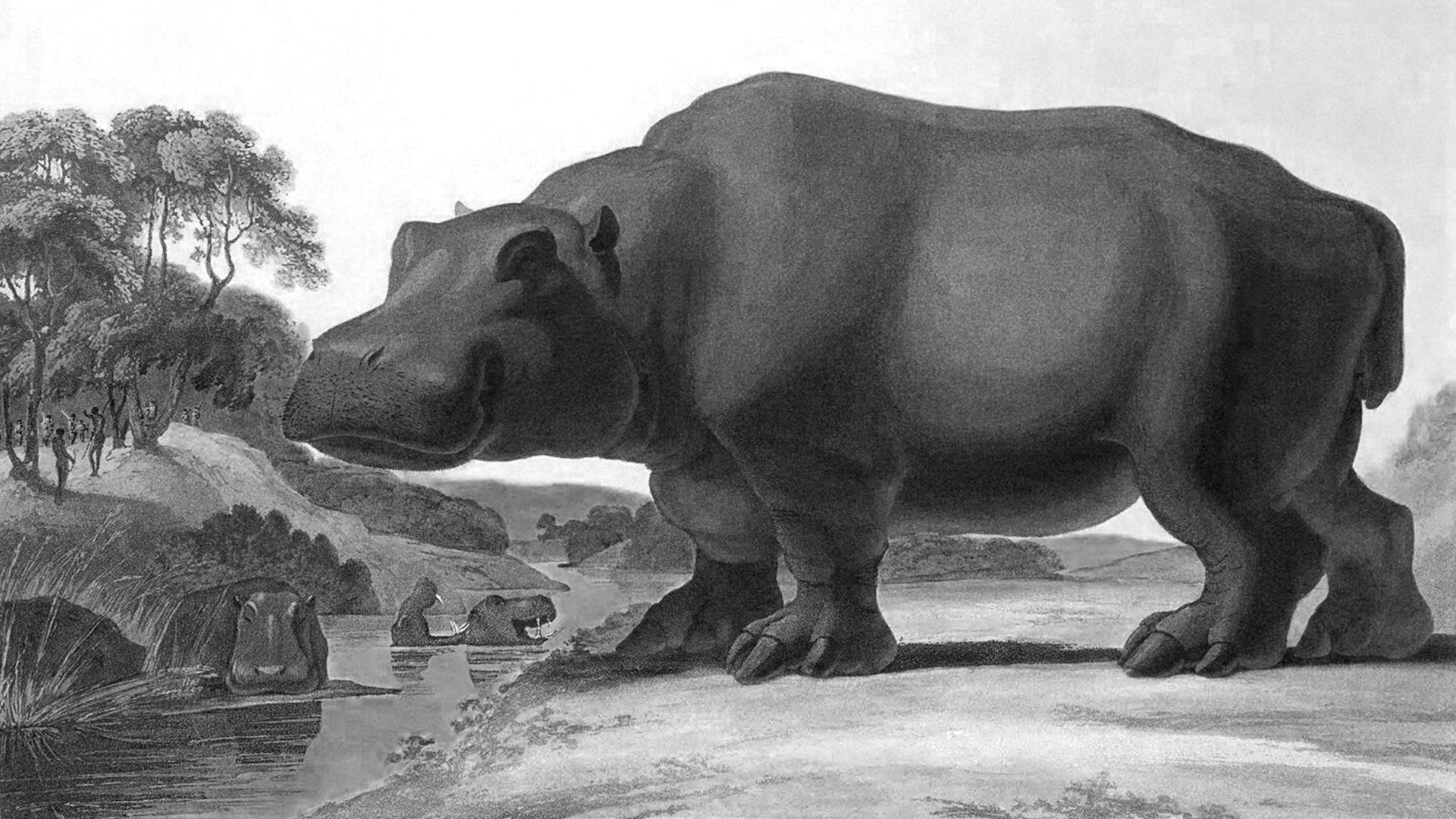

To better understand his process and creations, Moore researched the history of bone china, a type of ceramic developed in England in the mid-18th century when many European countries were seeking to replicate the bright white, translucent porcelain that was being imported from China. Though Spode wasn’t the first to experiment with adding bone ash to clay—that was English potter Thomas Frye—he did perfect the formula for bone china through rigorous testing.

“Spode experimented with several different bone ashes from different animals, the most notable being bones from horses, or equine, and cows, to figure out which one he liked,” says William Carty, a retired ceramic engineering professor at New York’s Alfred University. “He found that horses metabolize the iron that’s in whatever they eat, and so the bone china isn’t white. Cows, on the other hand, don’t do that, so the bone ash is white, and therefore the bone china they generate is also white.”

Like the elegant teacups of the Georgian period, Moore’s pieces are a bright, creamy white and translucent. Slip-cast in molds that the ceramist also makes, they have a quiet aesthetic that allows the restaurant's ingredients to shine. The plate and bowl are relatively conventional in shape (each piece is slightly different due to the artisan slip-casting and firing process), but the standout object in the collection is the water cup: Each weighs only about 4 ounces, with a tissue paper–thin body that shimmers as gently filtered light passes through. Because they are so thin, and because they’re fired at such high temperatures (about 2,400 degrees F), the cups tend to warp, resulting in one-of-kind irregular shapes.

“There’s a sensuousness with the water cup,” Moore says. “The ones that warp a lot have a relationship with the hand that’s really beautiful.”

Moore is one of the only artists in the country—if not the world—who makes his own bone china, starting with the bone. While there are other artists who are known for working in the field, including South Africa’s John Shirley and the U.K.’s Sasha Wardell, they add mass-manufactured bone ash to their clay recipe or use a prepared clay body.

“I haven’t run across very many people who feel a benefit, feel a need to work in bone china,” Carty says. “Artists tend to be acutely aware of the cost of raw materials, and bone ash isn’t cheap because it has to go through a lot of process steps to get to you.”

Lucky for Moore, he has a ready source for bone ash. And recently, he developed what he calls “200-percent bone china.” Because they are not glazed, broken or chipped dishes from the restaurant can be ground up and recycled into new pieces. The name is a play on Barber’s 200-percent whole wheat bread—made with flour milled from a wheat cultivar developed just for him, plus an equal amount of bran and germ from other strains of wheat.

And that’s one of the things that Barber really likes about it. “When Gregg’s bone china breaks, it can be ground up and recycled into new plates and cups, so it can be infinitely upcycled. It truly respects and makes use of every part of the animal—and does so in a way that reflects the land and farming practices that produced it. The plates literally give continued life.”

* As of January 11, 2025, Blue Hill at Stone Barns is temporarily closed due to a small fire. Check their Instagram for updates on repairs and reopening.

What's Your Reaction?

![American Airlines Customers Keep Complaining About Getting Trumped For Upgrades By Pilots [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/pilot-upgrade.jpg?#)