Five Underrated Stephen King Novellas

The novella may be one of the great mysteries of modern literature. Clocking in at an estimated 17,000 to 40,000 words, this unique example of narrative fiction is usually designed to be consumed in one or two extended sittings. The novella’s challenging limitations demand more detail than a traditional short without offering the novel’s opportunity […] The post Five Underrated Stephen King Novellas appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.

The novella may be one of the great mysteries of modern literature. Clocking in at an estimated 17,000 to 40,000 words, this unique example of narrative fiction is usually designed to be consumed in one or two extended sittings. The novella’s challenging limitations demand more detail than a traditional short without offering the novel’s opportunity for indulgence or elaboration. Given these daunting challenges, the novella often feels like a dying art.

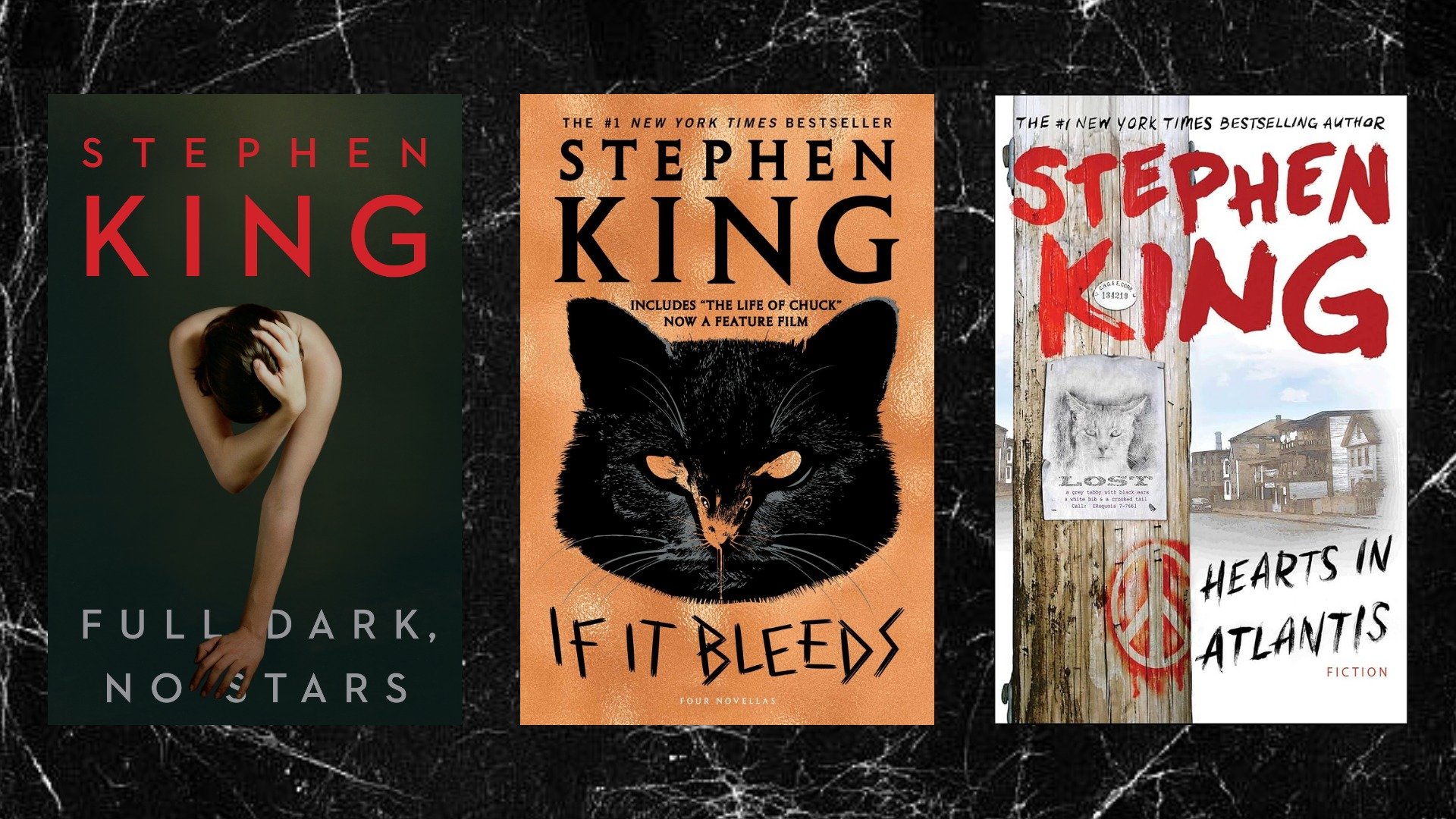

Stephen King’s mastery of this format grows stronger as time goes by, though. Since the 1982 publication of Different Seasons, it’s rare that a decade goes by without a new collection from the Master of Horror. These publications usually collect four novellas united by a particular theme. Though almost always well-received, some have become more prominent than others. Each anthology features a forgotten gem deserving of more literary love.

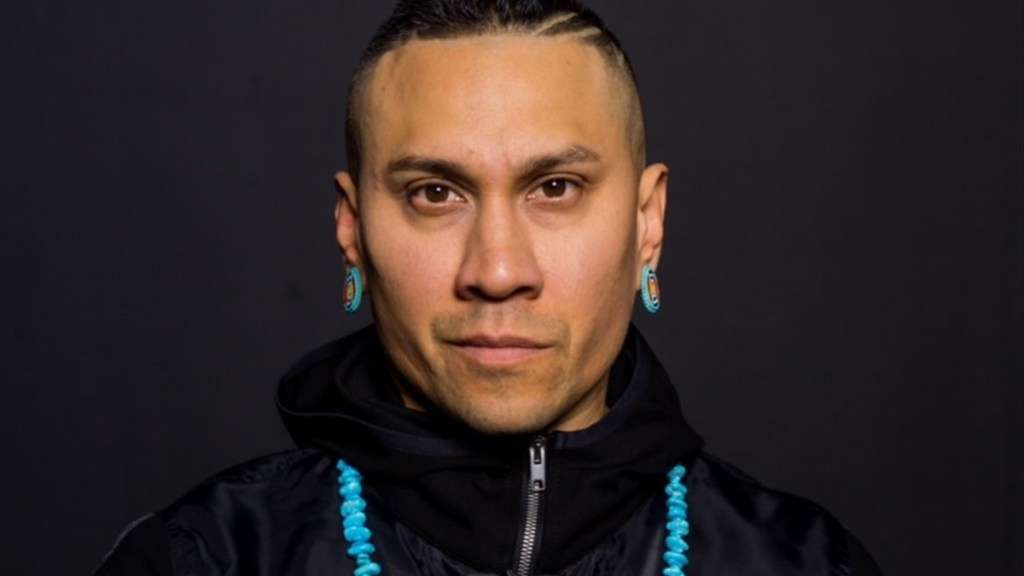

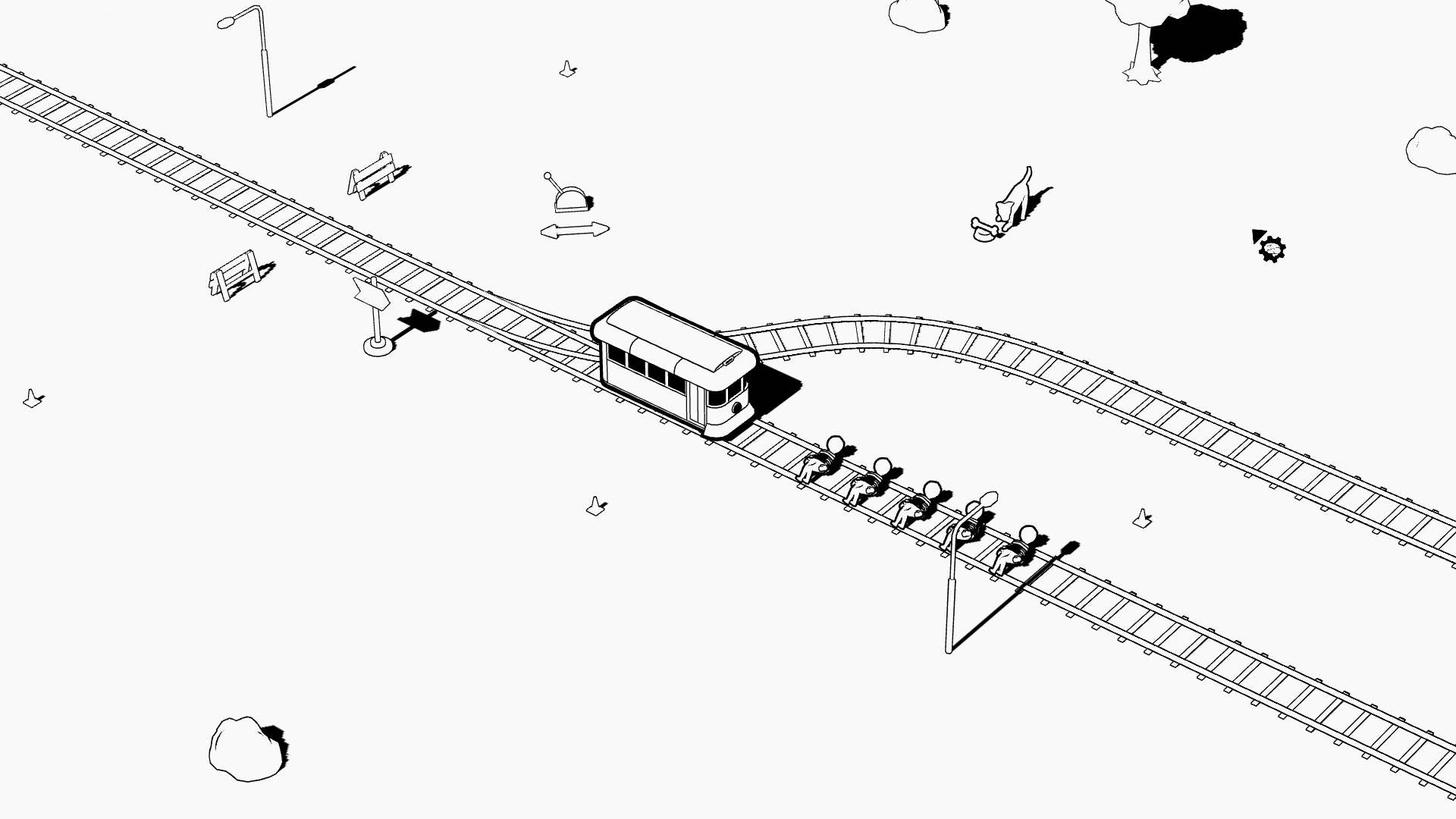

Many of his novellas have led to his best adaptations — The Shawshank Redemption, Stand By Me, come to mind — and this week sees The Life of Chuck following that tradition. Directed by Mike Flanagan, the star-studded feature sees the filmmaker returning to King’s Dominion to adapt another tough-as-nails story for the silver screen. Get your tickets now and read ahead to learn more about Chuck and four other King novellas you may have missed.

The Life of Chuck from If It Bleeds

Nestled in the middle of this quirky collection is King’s most experimental novella to date. The Life of Chuck is a meta-textual examination of impending death told through three distinct chapters delivered in reverse order. The first act, “Thanks, Chuck” hints at post-apocalyptic terror as Marty watches the world around him slowly crumble. Strange signs noting “39 Great Years!” begin appearing in the strangest places. Act 2 introduces us to Chuck himself just months before a devastating diagnosis. A snapshot of unbridled joy, the mild-mannered accountant pauses an aimless lunchtime walk and delights a gathering crowd by dancing to a busker’s infectious rhythms. The first yet final act follows Chuck as a young orphaned boy determined to find joy in his grandparents’ house in spite of the haunted cupola on an upper floor.

The Life of Chuck is the rare King tearjerker that muses on the meaning of life. Act 3 could be interpreted as the prolific author struggling to let go of the many characters populating his own head while admitting that some of their stories will never be written. Act 2 reminds us to embrace the surprising joy we encounter every day while Act 1 serves as a warning against fixating on loss. King has spent decades exploring the horrors of death, but here he leans in to raw emotion and presents a bittersweet depiction of life’s random beauty.

Big Driver from Full Dark, No Stars

Of King’s twelve anthologies of shorter fiction, Full Dark, No Stars may be the most bleak. Published in 2010, all four novellas concern despicable men committing unthinkable acts. “Big Driver” is sandwiched between the parable of a farmer determined to murder his wife and a bitter tale of deceptive marriage inspired by the horrific crimes of Dennis Rader. In the collection’s shocking final entry, a dying man makes a faustian bargain that dooms his best friend to a life of sorrow. But the compendium’s second tale is one of the most disturbing stories of King’s post-millennial career.

Tess is a cozy mystery writer who accepts a last minute speaking engagement in a neighboring town. Returning home via a rural shortcut, she’s waylaid by nails surreptitiously placed in the road. Unfortunately, the man who arrives just moments later has no intention of helping to change her tire. The titular criminal beats and rapes Tess repeatedly before dumping her body in a nearby culvert. Battered, bruised, and left for dead, she manages to find her way back home and begins creating a plan for grisly revenge.

Though isolated by the extreme trauma, Tess finds compassion and strength in imagined conversations with her most famous character. A rare example of literary rape revenge, King takes an unflinching look at sexual assault and the revictimization that comes with choosing the report. Tess must weigh the costs of putting herself through a long and humiliating quest for justice against bloody revenge on her own secret terms.

Hearts In Atlantis from Hearts in Atlantis

King’s 1999 compilation is a bit of an anomaly. Of the five entries of variable length, each narrative stems from events described in the opening tale. “Low Men in Yellow Coats” is a heartwarming story of childhood bravery with surprising connections to King’s Dark Tower series. Thanks to Scott Hicks’ 2001 adaptation, which repurposes the collection’s unrelated title, many forget about the book’s second entry which sees King reevaluate his own college years.

The literary “Hearts in Atlantis” concerns Peter Riley, a student at the University of Maine whose freshman year is derailed by an obsession with Hearts. Marathon sessions of the addictive card game begin sweeping through his dormitory floor, pushing classwork firmly out of his mind. Ordinarily, this distraction would foreshadow the loss of a scholarship or a tense conversation with concerned parents, but King’s 1966 setting adds life or death stakes. Peter has received a draft deferment thanks to his college enrollment.

Should he fail his classes, he might be expelled and find himself on the front lines of battle in Vietnam. This poignant novella may be King’s most personal exploration of political action and the human instinct for self-preservation. Like musicians playing on the deck of the Titanic, Peter and his classmates have created a world of imagined safety and a way to distance themselves from reality. It’s not until anti-war protest infiltrates this unstable utopia that Peter—and King by proxy—must reckon with the cost of this comforting illusion.

The Sun Dog from Four Past Midnight

Four Past Midnight falls in one of King’s most experimental periods and the bizarre nature of each story bears this pattern out. The Langoliers is a strangely terrifying time travel nightmare while The Library Policeman explores addiction through the myth of a fear-eating monster. Secret Window, Secret Garden, the violent account of a world-famous writer confronting his own inspiration, proves to be the most grounded of the collection, but The Sun Dog may spark the most genuine fear.

The owner of a ramshackle curio shop, Pop Merrill cons a boy named Kevin Delevan into selling his malfunctioning Sun 660 Polaroid camera. Though seemingly working in perfect order, the device only produces pictures of a single image: a ferocious dog moving closer to the lens each time the shutter is deployed. This cynical and manipulative old man finds himself compelled to take photo after photo and begins losing track of objective reality. King builds horrifying tension as the slowly mutating beast grows closer and closer to breaking through the analogue barrier between worlds.

Though unique and certainly terrifying, The Sun Dog is not only overshadowed by the other entries in Four Past Midnight, but by King’s additional Castle Rock novels. Constant Readers usually mention Cujo, The Dead Zone, Needful Things and a handful of memorable short stories when referring to King’s iconic town, leaving this narrative curio out of conversation. However, this uniquely frightening story demystifies one of the Rock’s most notorious residents while providing a prescient study of addictive technology and the dangers we find lurking in unassuming devices.

The Breathing Method from Different Seasons

Of all King’s impressive collections, none can rival the heartbreaking beauty of 1982’s Different Seasons. This cyclical tome provides the source material for some of modern Hollywood’s most beloved films including the adorementioned The Shawshank Redemption and Stand By Me. Apt Pupil may be the darkest of the four, despite its classification as a summer story. But the book concludes with a forgotten masterpiece of feminist empowerment and bodily autonomy.

The Breathing Method begins on an ominous note as we’re introduced to the slightly sinister halls and shadows of an exclusive men’s club that may be a portal to other worlds. Shortly before Christmas Eve, Dr. McCarron regales the club’s members with a bleak and harrowing holiday tale. Flashing back to 1930’s-era New York, he describes the headstrong Sandra Stansfield as she prepares to raise a baby on her own. Dr. McCarron introduces an experimental new breathing method said to alleviate pain through focused respiration during delivery, but Sandra’s labor goes dreadfully wrong and the dedicated young mother-to-be winds up performing her “locomotor” breaths in unthinkable conditions. Not even death can keep this courageous woman from protecting her child.

Though often overshadowed by the anthology’s more iconic entries, The Breathing Method is a devastating rumination on reproductive rights and a haunting appraisal of motherly love.

The Life of Chuck is playing in theaters everywhere. Get tickets now!

The post Five Underrated Stephen King Novellas appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.

![“[You] Build a Movie Like You Build a Fire”: Lost Highway DP Peter Deming on Restorations, Lighting and Working with David Lynch](https://filmmakermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/1152_image_03-628x348.jpg)

![Double Dealing [THE FISHER KING]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/the-fisher-king2.png)

![Dan Gilroy Talks ‘Andor,’ Tyranny, Writing Mon Mothma’s Fiery Speeches, Bix’s Great Sacrifice & More [The Rogue Ones Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/13114943/Dan-Gilroy-Andor-Interview.jpg)

![Freakonomics Says United Pays $33 for Every Business Class Meal—Here’s Why That Number Doesn’t Work [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/20220619_113816-scaled.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg)

![[Podcast] Problem Framing: Rewire How You Think, Create, and Lead with Rory Sutherland](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/rort-sutherland-35.png)