The 20 Best Films of 2025 So Far

Our staff picks 20 films from 2025 that stand out from the crowd.

What a strange year it’s been. As the divisions in the country continue to widen, people turned to a truly strong year for film and television, but even that unfolded in the shadow of industry controversies around the increasing use of A.I. and the diminishing of the mid-budget movie. With the ascendance of streaming services and the domination of the familiar at the box office, it felt a little harder to find the gems, but they were definitely out there. (And people lined up en masse for one of them in this feature, making it the most essential blockbuster in years.)

We asked our regular critics to pick a few films that they loved from this year and then whittled the resulting list of over 100 films down to 20 that seemed to really tell the story of 2025 so far. Will we still remember these films in six months when people are writing about the best of the year? We hope so. Don’t lose track and click through on each title for full reviews (when available). Also, we’re including streaming availability as of today, but that’s very subject to change.

“April“

Set in a rural Georgian village at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains, Dea Kulumbegashvili’s enigmatic and unsettling abortion drama “April” features a tremendous performance from Ia Sukhitashvili as Nina, an obstetrician whose illicit actions supplying patients with birth control and performing off-the-books abortions are jeopardized when she becomes entangled in a negligence investigation at the hospital where she works. The film, which has played numerous festivals since its premiere at the Venice Film Festival, where it received a Special Jury Prize, evokes not only the stark and surreal beauty of the region, but also uses immersive static shots to transport viewers directly into the rocky emotional terrain of Nina’s conflicted soul.

In my conversation with Kulumbegashvili, she shared her ambitions for the film, stating, “My objective was to create a film which would be a female experience. A female experience, not only in terms of political activism or the social aspects of it, but literally, physically living in this world. What does it mean for a woman? This film was for me, and is now for me, a collective effort, because it does consist of all the elements brought to me by different women. And because of that, it was very important that the film grasped and captured, first of all, the physical experience. I hope that the rest can be put in or brought in by the viewer.” – Marya E. Gates

Currently in limited theatrical release.

There are remote towns in the UK with eccentric innkeepers who welcome you by putting on the kettle for a nice cup of tea. Conversations are never intrusive, that would be rude; and yet you somehow exchange just the right amount of information. I thought of those towns when watching James Griffith’s sweet film “The Ballad of Wallis Island,” starring Tim Key, Tom Basden and Carey Mulligan. (Basden and Key co-wrote the screenplay.) However, in this film, the town is a remote island reachable only by boat. And the innkeeper—well, is not an innkeeper, but a lottery winner (Tim Key) who has invited a faded musician (Tom Basden) there to play a concert. The musician thought his audience would be less than a hundred people but did not know it would be an audience of one. The details are not important: the lottery winner’s wife died, and they enjoyed the folk music duo of McGwyer and Mortimer (Carey Mulligan), wanting them to reunite for one last concert. What happens is a gentle mix of low-key conversations, flashbacks, and just life, living it a day at a time on a sea-swept island, allowing each character to find a connection with the next. – Chaz Ebert

On Peacock.

In the second of Steven Soderbergh’s 2025 releases, a British intelligence agent (Michael Fassbender) is charged with deducing which one of five colleagues is plotting to steal a cyber-device that could be extraordinarily dangerous in the wrong hands—a mission that becomes even more complicated when his wife (Cate Blanchett) is one of the names on his list. As narrative hooks go, that is certainly a grabber. The rest of the film more than lives up to its promise, thanks to a smartly written screenplay by David Koepp, strong performances from the entire cast (including Tom Burke, Marisa Abela, Rege-Jean Page and Naomie Harris as the other suspects and Pierce Brosnan as the head of intelligence), the off-the-charts chemistry between Fassbender and Blanchett and the deft manner in which Soderbergh deploys these elements for maximum impact.

There is not a wasted or uninteresting moment to be had here: the extended dinner party sequence early on in which Fassbender brings his suspects together to observe them is an absolute masterpiece. Even though it consists almost entirely of people conversing in rooms and you can count the number of bullets fired throughout on one hand, it is never less than riveting throughout its blessedly brief 93-minute run time. Its relative non-performance at the box-office probably won’t help future mid-budget films aimed at adult audiences—the kind the studios used to churn out once upon a time regularly. But my guess is that this one will go on to be rediscovered by future audiences who will revel in its multitude of pleasures (while wondering how foolish we were for allowing it to fall by the wayside). – Peter Sobczynski

On Peacock.

“Eephus“

There’s a cadence to the action (even when inept) in “Eephus” that reflects what director Carson Lund most cherishes about baseball: its unhurried quality allowing both participants and spectators to luxuriate in the intricacies of the sport for as long as necessary. Lund’s bittersweet comedic tribute to America’s pastime is not so much concerned with the abilities of the players on the field—the majority of them middle-aged men exhibiting figures molded by routine rather than rigorous training—but in using baseball as a vehicle to observe their personalities and bonds with one another.

For these recreational teams, the River Dogs and Adler’s Paint, trash talk is their love language, yet while they won’t express it, there’s an underlying heartache to this game. It’s the last they’ll ever play here since the field is being demolished. Lund and co-writers Michael Basta and Nate Fisher (also an actor in the film) introduce a cast of characters that range from the most memorably raucous to those who wish to maintain these tenuous friendships beyond this moment but might not be reciprocated. As the day turns into night and the stubborn lot carries on playing in darkness, one inevitably wonders what will happen to them the following weekend when they no longer have this sacred space of togetherness. – Carlos Aguilar

On VOD.

To call Sarah Friedland’s “Familiar Touch” a coming-of-age story is to recognize, as this feature debut does so exquisitely, that all of us are always coming of age, all the time, regardless what seasons of life we find ourselves experiencing. For Ruth (the magnificent Kathleen Chalfant), an octogenarian woman transitioning to life in a memory-care facility, this period of older adulthood too often associated in popular culture with linear erosion or decline instead feels like the start of a new chapter. Forthright and fiercely self-possessed, Ruth must adjust to assisted living after decades of independence. But even as her cognitive capabilities diminish, she retains a sense of self—really, a sense of all the selves she has been—through touch and gesture.

As Ruth floats in the care community’s therapy pool, memories of a long-ago childhood wash back over her; preparing breakfast for the residents with a chef’s knife in hand brings forth the discipline honed during her years as a professional cook. Friedland, a filmmaker and choreographer, grounds her film in Ruth’s point of view through her focus on the intimacies of movement and embodiment; and Chalfant, dignified and expressive as a woman navigating a self that will remain fluid yet irrepressibly hers, delivers one of the great performances of the year. This is a special film—not only for its radiant sensitivity, quiet honesty, and effervescent humor, but for the care it takes in depicting a senior living community, rarely represented on screen, with the compassion and attention its residents and workers deserve. – Isaac Feldberg

Opens in limited theatrical release on June 20th, wider on June 27th.

Filmmakers Scott McGehee and David Siegel pull off a tricky feat in this adaptation of Sigrid Nunez’s 2018 novel of the same name: Creating a dog movie that acknowledges yet deftly sidesteps nearly every trope of the genre, and doing so in a richly dramatic, archly funny, and poignant fashion.

Naomi Watts effortlessly navigates her performance as Iris, a creative writing professor and novelist whose life is already in flux before her charming but misanthropic mentor Walter (a perfectly cast Bill Murray) dies by suicide, leaving her to inherit Walter’s beloved Great Dane, Apollo. As Apollo literally and figuratively takes up so much space in Iris’ life (and her small, rent-controlled, no-canines-allowed apartment), “The Friend” hits many of the expected notes in a film about processing grief, but almost always in a fresh way. With the real-life animal actor Bing playing Apollo (no CGI creation here, thank the movie gods), the journey of emotional healing becomes a shared experience; Apollo is grieving Walter just as much as Iris.

Cinematographer Giles Nuttgens and production designer Kelly McGehee imbue the film with a lovely albeit somewhat idyllic viewscape of New York City.

It’s easy to mine comedy from the pairing of a harried Manhattanite loner with a dog so colossal you don’t have to bend over to pet him, and “The Friend” indulges in a few such moments, but then it’s back to the business of telling a sharply observed story that avoids becoming saccharine as it hits resonant emotional notes. – Richard Roeper

On VOD.

Produced on the fly in an active war zone with no money, and in some cases no food or shelter, this extraordinary anthology of 22 short subjects from occupied Gaza is a testament to the enduring power of art, even when the society that it portrays is in ruins. Put together by director-producer Rashid Masharawi, it’s an inspiring work of survivorship that doubles as an all-in-one tour of different modes of expression. There’s fiction and nonfiction in here, comedy and drama, prose and poetry, even some experimental touches. The formats are all over the place—whatever they had, basically.

The unifying thread is the sense that everything was patched together on the run, under unmerciful pressures that most filmmakers can’t imagine. Imagine deciding whether to take a second take of a very long shot that temporarily brings you into the view of snipers. It brings a whole meaning to the phrase “making the day.” And it creates a record of a time and place that was disappearing even as the movies were being shot. And the filmmakers, of course. How many of them are still alive? How many other contemporary films would prompt a question like that? – Matt Zoller Seitz

On VOD.

Only a sci-fi epic with multiple Robert Pattinsons and hundreds of formidably adorable creatures (called creepers) could ever hope to house director Bong Joon-ho’s madcap sensibilities. His “Mickey 17” is as gloriously messy as it is emotionally stirring, and its unwieldiness is a feature, not a bug. It’s prophetic in its lament and righteous in its anger, a paroxysm of indignation against systems that equate someone’s value with their usefulness.

Taking place in the year 2054, Pattinson plays Mickey, an “expendable” who is part of an interplanetary mission to colonize the ice planet, Niflheim. Dying is the name of his vocation, and Mickey is tasked with doing the unsavory, unwanted, and outright dangerous tasks aboard the colony, and such acts almost always lead to his demise. Upon death, he’s “reprinted” with his old memories but tasked to do the same grueling work; The expedition is led by the egomaniacal couple of Kenneth (Mark Ruffalo) and Ilfa Marshall (Toni Collette), who eagerly flaunt their inhumanity towards their crew members, particularly Mickey, but who gloss it over in the name of efficiency and progress.

Bong has used his projects, with all of their absurdities and horrors, to critique the indignities capitalism imposes on the most vulnerable and destitute, and “Mickey 17” is the Korean director at his most unvarnished, where he pours out his frustrations against corporate indifference and malice with vociferous aplomb. It’s easy to read his indictment of Marshall and Ilfa as a Trump and Musk allegory (Marshall’s followers don red caps). But Bong’s eye has always been bent towards the global, and it’s more accurate to say that he’s lamenting the ways absolute power breeds a soul-corroding rapaciousness. In our crumbling world, sometimes it’s best to leave subtlety behind when reprimanding fascism and egomania in all its forms; why use a megaphone when a sledgehammer will do? – Zachary Lee

On HBO Max.

Guinea fowls, as we learn in Rungano Nyoni’s blistering second feature, are “talkative creatures,” small, excitable birds whose insistent clucking actually serves an important purpose: Altering their fellow savannah-dwellers to the presence of predators. This is a metaphor, of course, although its true meaning doesn’t snap into focus until the very end of the film. When it does, it’s breathtaking.

Until that point, “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” plays like an African take on Buñuel, spinning sardonic comedy from the absurdities of life in modern-day Zambia. The film follows Shula (Susan Chardy), an upwardly mobile young woman who wants no part of her family’s performative mourning when her dirtbag uncle Fred is found dead by the side of the road late one night. Shula is the one that finds him, while coming back from a costume party dressed like Missy Elliott from the “Supa Dupa Fly” video.

The contrast between traditional and modern, sober and whimsical, in that image is typical of Nyoni’s vision. On the whole, she has no use for hypocritical aunties who turn a blind eye to abuse while proclaiming themselves Christians. But she finds something worth fighting for in vulnerable girls like Shula’s cousin Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela), who’s depicted as a drunken fool until the traumatic origins of her self-destructive behavior are revealed.

That’s when the film shifts from a farce to a tragedy, then a burn-it-all-down polemic against patriarchal oppression and the silence of women who value their men’s comfort over their girls’ safety. Nyoni’s command of tone is masterful, and her purpose clear and righteous. Seeing her—and her heroine—step into her power and sound the alarm is electrifying. – Katie Rife

On VOD.

We call intimately epic movies centered on expansive human journeys novelistic at times, as if to make an intangible quality of a certain type of cinema tactile for the readers. Think of thoughtful and expertly realized design touches, stories that gain complexity against historical backdrops, complicated families that move through time as best as they could within their circumstances. Much of these features are a part of Daniel Minahan’s elegiac “On Swift Horses,” a poetic adaptation of Shannon Pufahl’s novel, written for the screen by Bryce Kass. The period is the 1950s, and the backdrop is the rise of polite society across suburban settlements; a time of neighborly visits, race tracks, and distant mushroom-cloud explosions watched with intrigue by those in clean-cut three-piece suits and cinched-waists.

But what if you are queer in such a time that insists upon a false idea of normalcy, like the reserved Muriel (Daisy Edgar Jones) and her brooding brother-in-law Julius (Jacob Elordi) are? How do you discover and embrace your identity, your community when what surrounds you tries to invalidate them? We’ve seen period tragedies of gay men and women not allowed to live their truth before, tragedies with victims and villains. While “On Swift Horses” isn’t exactly a happy story, it is one that refreshingly avoids the cliched notions of a villain (e.g. playing Muriel’s husband, Will Forte never becomes that), which is one of the film’s greatest assets.Instead of taking those narrative shortcuts, this quietly affecting movie gives everyone enough room to breathe and to evolve, shining through its sensual moments anchored in gorgeous details. (It’s the kind of film that makes you taste the tang of a black olive.) Those in search of something volatile need to look elsewhere, but for the rest of us who’d like to sit with quiet feelings for a while, “On Swift Horses” is a gift. – Tomris Laffly

On PVOD.

“One of Them Days” is the funniest film of the year so far, deliriously silly, outrageously over-the-top, and as heartwarming as it is fun. It has a classic screwball comedy set-up: good-hearted underdogs played by performers with a gift for physical comedy face a series of obstacles as they try to achieve a more secure and fulfilling level in the societal hierarchy. The relatable stakes are established quickly: Keke Palmer plays Dreux, a waitress who has a crucial job interview for a supervisor position at 4:00. She and her best friend and roommate, the free-spirited artist Alyssa (SZA) have to raise the rent money and get it to the landlord before 6:00. And an enraged woman and a local crime lord are chasing after them. This leads to an escalating and hilarious series of adventures and encounters including a predatory lender, a skeezy sneakerhead, and a blood bank, with wildly funny appearances by Keyla Monterroso Mejia, Lil Rel Howrey, and Janelle James.

The endless charm and dazzling chemistry of the two leads give a buoyant jubilation to even the direst situations they face. The specificity of the setting, almost entirely in a Black community, avoids the usual “relatability” compromises. That keeps the details of the story fresh, with a gloss of authenticity that grounds even the most outrageous plot developments and makes the Capra-esque happy ending even more satisfying. – Nell Minow

On Netflix.

“Presence“

Steven Soderbergh’s first of two films of 2025 is one of the master’s most playfully brilliant, putting viewers in the shoes of a presence haunting a family that has just moved into a new home. In a sense, Soderbergh, who shoots his own films under the pseudonym Peter Andrews, becomes a character in “Presence,” using his underrated craft behind the camera to give this mysterious spirit personality and purpose. He’s been a master for decades, but what’s been so impressive about Soderbergh’s recent work has been its efficiency. In an ear of bloated, pretentious cinema, Soderbergh delivers tight, lean, perfectly paced films. Sometimes even two in one year.

The original construction of “Presence” stole too much of the spotlight around this movie. It’s not just a gimmick. It’s a new way to tell what is ultimately revealed to be an emotionally powerful story of loss, and it’s even a commentary on the art of filmmaking itself. After all, a director, especially one who is also the cinematographer, is a “presence” on every set, choosing what we see and what’s hidden behind closed doors. And, on top of all of that, it has another thing we’ve come to expect from Soderbergh: an ensemble without a single weak link.

In an era when “elevated horror” has become its own genre, an Oscar winner went back to the roots of the ghost story, reminding us of the power of things that go bump in the night or the squeak of a door that shouldn’t be opening by grounding the impossible in something he knows more about than anyone: filmmaking. – Brian Tallerico

On Hulu.

The advance word on “The Shrouds” was that it was something different from writer-director David Cronenberg’s provocative, ahem, body of work. That it was meditative, about grief, and inspired at least in part by the death of the artist’s wife Carolyn in 2017.

And it is indeed all of those things. It’s also a movie in which the sci-fi element is so organically (and relatively nonchalantly) incorporated into the narrative and the mise-en-scene that its premise—the titular “shrouds” are part of an apparatus that allows mourning survivors of a buried corpse to look in on it as it rests—seems not particularly far-fetched at all. As has been the case in all of Cronenberg’s work (even the movies in which people’s heads explode, or abdomens become VHS cassette players), “The Shrouds” is precisely modulated.

And it is also 100 proof Cronenberg. For as much compassion as it shows its characters — Vincent Cassel, a stand-in for the director, plays the widower who invented the technology, Diane Kruger his not-quite-departed wife (and her lookalike, still-living sister) and Guy Pearce as a coming-apart inventor (a bit of a recurring character in Cronenberg) — the movie is also unsparing in its honesty about bodies, which grows more discomfiting as the film goes on. This is despite Cronenberg’s own ability to take a convincing, clinically detached stance. (Which extends, apparently, to his real life as well: discussing his “Dead Ringers” in the book “Cronenberg on Cronenberg,” back in the 1990s, he drily said, “I don’t want to discuss whether I’ve looked up my wife with a flashlight or not, but absolutely I wouldn’t be afraid if I needed to”) But in the end, “The Shrouds” is anything but detached. It’s an endlessly moving cry of mourning. – Glenn Kenny

In limited theatrical release.

“Sinners“

In an increasingly risk-averse period of studio filmmaking, intellectual property-driven franchises seem like the closest thing to a safe bet. Ryan Coogler’s “Sinners” stands out for the scale of its risk and the audacity of its conception. The writer-director struck a deal with Warner Bros. that is rare for filmmakers, and perhaps unprecedented for a Black filmmaker: he got the final cut, first-dollar box office gross participation, and a provision that gives back ownership of the movie in 2050. The gamble paid off beyond anyone’s imagination when “Sinners” became the top-grossing film of the past 15 years to be based on an original story.

The movie tells the tale of twin brothers (Michael B. Jordan) who travel back to their segregated Mississippi hometown from Chicago, where they worked for Al Capone, to open a juke joint, only to encounter obstacles both sociological and supernatural. It’s a period drama, a portrait of pre-World War II segregation and the concept of “provisional whiteness,” a sexy movie with two entire romances in it, a foot-stomping musical about how homegrown art defines groups and historical eras, and a gory, unnerving horror movie. It was all so expertly directed and acted that viewers tended not to notice all of the virtuoso throwaway touches in the production itself, like the two Jordans passing a lit cigarette to each other. It helped that Coogler is a gifted salesman who never seems like he’s selling. One of his masterstrokes was a short Kodak video explaining motion picture film aspect ratios to viewers who didn’t know what they were and telling them they’d have the best experience in IMAX, a format the movie was partly shot with. Everything about this film is a demonstration of the heights to which popular filmmaking can ascend, if it has the nerve. – Matt Zoller Seitz

On PVOD.

Eva Victor’s feature-length directorial debut, “Sorry Baby,” is a nuanced portrait of moving through trauma. Something bad happened to Agnes (Eva Victor), and “Sorry, Baby” is Victor’s chaptered tale of how to reckon with a world, body, and self seen through new eyes. As Agnes comes to terms with the event, she’s shouldered by her best friend, Lydie (Naomi Ackie), and the two boast a sensitive and palpable chemistry. Their relationship, in addition to Agnes’ wry humor, lead the film to comedic territories that feel realistic rather than gifted, but still span the emotional spectrum.

The finesse of Victor’s pen takes us from earth-stopping quietude in a bathtub scene where Agnes confides in Lydie to a somehow darkly funny hospital exam where the two link arms against a seriously ill-compassioned doctor. Lucas Hedges’ Gavin, is the meek but loveable neighbor whom Agnes starts to see new light in, and the two’s warm chemistry eeks out of every humorously awkward encounter. It’s these relationships that Agnes digs her heels into to stop from sliding, and they form the tenderness of the film.

Victor’s “Sorry, Baby” is a heartful, funny testament to pain and time, with an especially moving curbside scene reminding us that all measures of time can be both near and far away. Giving ourselves the grace to tread through weedy waters is all we can do until we find our clearance, in whatever form that may take: a kitten, a baby, or just yourself. –Peyton Robinson

Opens on June 27th.

One of the privileges of doing this job is anticipating a promising filmmaker’s next leap. When I first watched Haley Elizabeth Anderson’s evocative queer coming-of-age short “Pillars” at Sundance 2019, I sensed she was someone to keep an eye on. Her later short co-directed social justice documentary “The Sentence Of Michael Thompson” only increased my curiosity. But her debut feature, the arching, handmade “Tendaberry,” which premiered at Sundance 2024, exceeded my wildest hopes.

A real kitchen sink of a film, “Tendaberry,” whose chapters are divided by the four seasons, follows Dakota (Kota Johan), a 20-something-year-old woman on the verge of experiencing every possible trial and tribulation while living in New York City. She will lose her boyfriend Yuri (Yuri Pleskun) when he returns home to Ukraine to care for an ill father. She will become pregnant and homeless, isolated and confused, and desperately yearn for community in a cooling city.

Anderson intermingles Dakota’s journey with 16mm footage of Coney Island shot by real-life videographer Nelson Sullivan. The use of the archival gives Dakota some company, providing a sense that someone else in a different time, walking at a different pace, has felt the feelings she is now experiencing. Anderson also leans on frenetic handhelds and breathtaking montages to visually elaborate on the fears and hopes held by Dakota.

Even when “Tendaberry” saunters to the edge of ruin, there is an excitement to its raw ambition. This is the kind of film that so clearly and firmly announces the emergence of a new voice, it’s impossible not to absorb its fervent call. – Robert Daniels

On MUBI.

Emilie Blechfeldt’s folk horror debut is the ultimate fractured fairy tale: Fractured bones, fractured egos, fractured souls. In a twisted take on the Cinderella fable dedicated to taking the story back to its Grimm-er roots, Lea Myren plays Elvira, the ugly-duckling daughter of a social-climbing widow (Ane Dahl Torp) whose latest gambit to marry rich falls flat on its face when the guy croaks and they discover he has nothing. Here, the effortlessly beautiful Cinderella (Thea Sofie Loch Næss’s Agnes) is but a jealousy-inducing impediment; to keep up, Elvira will have to endure all manner of body/beauty horror at the hands of her mother and a macabre cosmetic surgeon named Dr. Esthétique.

Echoes of “The Substance” abound, of course, both being consciously unsubtle treatises on the ways women will destroy themselves to attain some standard of beauty and the social capital therein. But where Coralie Forgeat’s film blasts you with the bright, vibrant colors of Hollywood, Blechfeldt keeps “The Ugly Stepsister” coated in a hazy fairy-tale feel, whether in the stately, candlelit interiors of their decaying mansion or Elvira’s honeyed fantasies about earning the Prince’s favor.

Every single thing Elvira does to herself—the clink of a broken septum, the toe-cutting, the tapeworm—is squicky and gruesome and tragically framed. Elvira’s not a bad person, after all. She’s just a product of her circumstances, a world desperate to squeeze her into a mold she doesn’t fit into, even if it’ll crunch her up in the process. Blechfeldt refuses to let us look away from each stomach-churning step along that road, which is what makes “The Ugly Stepsister” so perversely riveting. – Clint Worthington

On Shudder.

“A movement that celebrates the dream, the other, and the unconscious offers limitless possibilities.” That’s esteemed art critic Jed Perl from a wide-ranging article on surrealism in the New York Review of Books. And this is Canadian filmmaker and neo-surrealist Matthew Rankin in conversation with Filmmaker Magazine’s Scott Macaulay: “There’s not a lot of mythmaking in Canada, so, by design, I think there’s the sense that it is artificial[…]there is no resounding myth. There’s no eagle.”

There are, however, a number of turkeys—dead and alive—in “Universal Language,” Rankin’s dizzyingly inventive sophomore feature. His turkeys are a playful variation on the green goose featured in the logo of the Kanoon Institute, the Iranian organization that produced several early films by Abbas Kiarostami.

Turkeys are also the first of many well-synthesized influences on Rankin’s semi-autobiographical fable, set in a fictitious Iranian-Canadian community living in Winnipeg’s historic/imaginary Beige and Grey districts. Three stories intersect, including a bittersweet road trip that follows an estranged bureaucrat (Rankin) who quits his day job and trudges back to Winnipeg to see his estranged mother.

There’s room enough in Rankin’s accommodating tent for local filmmakers like Guy Maddin and John Paizs, as well as Iranian masters like Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Jafar Panahi, Jacques Tati, and regional ad men, too. And at the heart of Rankin’s polyglot countermyth is a mantra based on the usual “in the name of God” invocation that prefaces most Iranian movies: “In the name of friendship.” The movie that follows is equally surprising and disarming throughout. – Simon Abrams

On Kanopy and VOD.

For a time, you feel like you know what Vietnamese writer/director Trương Minh Quý’s tender showcase “Việt and Nam” is about. It begins as a delicate queer romance shared by Viet (Đào Duy Bảo Định) and Nam (Thanh Hải. Smeared), two coal miners whose sensual and emotional yearning for one another powers an early narrative that includes quiet eroticism and loving embraces. Before long, however, Nam decides he wants to leave the country. Viet opts to follow.

You would think, Quý’s film would then become a standard ‘lovers on the run’ type joint. But it doesn’t. In fact, the magic of “Việt and Nam” is how it swerves when you expect it to turn.

The film transforms into a kind of ghost story. The spirits here, however, aren’t necessarily otherworldly specters. They’re the scars of a country whose past includes the Vietnam War and whose present features queerphobia and citizens risking their lives to become refugees on arduous sea journeys. Because of these realities, a certain grief pervades Quý’s exquisite visual and narrative rhythms. The bumps in Quý’s tranquil surveying of the Vietnamese landscape is the mourning Viet and Nam feel for each other and for their country, a homeland they’re inextricably linked with, but whose history makes it now impossible to survive.

In that sense, the relationship at the center of “Việt and Nam” often recalls the devastating brokenness of “Hiroshima, Mon Amour,” another film that places a fragile romance in the still open wounds of a fractured country. But once again, even when you think you know what “Việt and Nam” is about, it surprises you. This film ends with a final shot, set amid the twinkling beauty of coal dust, that so emphatically rips your heart out, you can’t help but feel naked and awed. – Robert Daniels

On MUBI.

Joel Potrykus and his characters live on the edge. Of poverty, of society, of danger; the American experiment fails and rifts in space and time open and it’s an open question whether his damaged heroes fall in or out. Vulcanizadora, to date his best work, puts the bare essence of American masculinity (as assayed by two overgrown children played by the director and his frequent leading man Joshua Burge) into stark relief, surrounded by unfeeling, unforgiving midwest greenery. They carry tokens of their childhood with them like talismans and Potrykus’ Derek keeps telling Burge’s Marty that things will be perfect when they get where they’re going, lending their odyssey a distinct patina of folk horror.

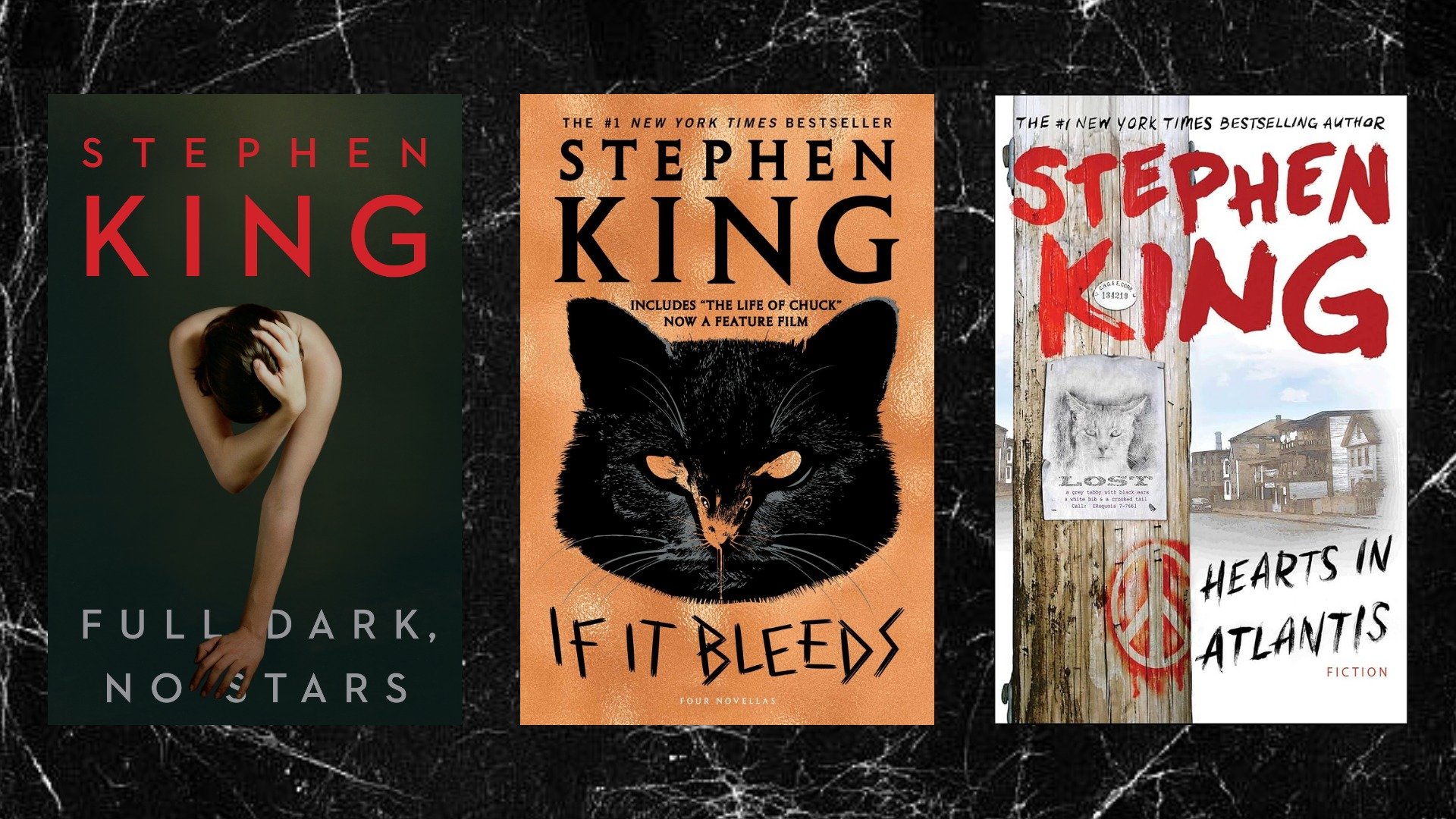

Just what are they going to do when they get wherever it is they’re going? Potrykus implicitly asks the same thing of every weekend warrior and pop culture obsessive watching civilization crumble. As these two dead enders embrace their inner Bam Margera the creeping despair of the mission becomes impossible to ignore. This deeply sad tale of lost potential is everything this great director does well; an autopsy of the American dream, a sun burnt body full of junk food and micro plastics. Having failed to make their wayward childhoods into satisfying life, they attempt to stare down death with the same lack of conviction with which they approached life. A Stephen King nightmare in a Lisandro Alonso body. – Scout Tafoya

In limited theatrical release.

![‘The Life of Chuck’ – Mike Flanagan & Kate Siegel Spotlight the Horror Stars in Stephen King Movie [Video]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-12-134913.png)

![‘Yellowjackets’: Christina Ricci Talks Misty Quigley’s Evolution, That Leather Jacket, Her Complicated Walter Bond & The Show’s Shifting Arc [Interview]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/12125824/Christina-Ricci-Yellowjackets.jpg)

![‘Dying For Sex’: Creators Liz Meriwether & Kim Rosenstock Talk Michelle Williams & Jenny Slate Fearlessness, Sexual Awakenings & The Intimacy Of Showing Up For Friends [Interview]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/04151935/FXs-Dying-for-Sex-Media-Guide-3.jpg)

-35-45-screenshot.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

-30-7-screenshot_0FxoE4J.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Problem Framing: Rewire How You Think, Create, and Lead with Rory Sutherland](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/rort-sutherland-35.png)