Jia Zhangke and the Chinese Century

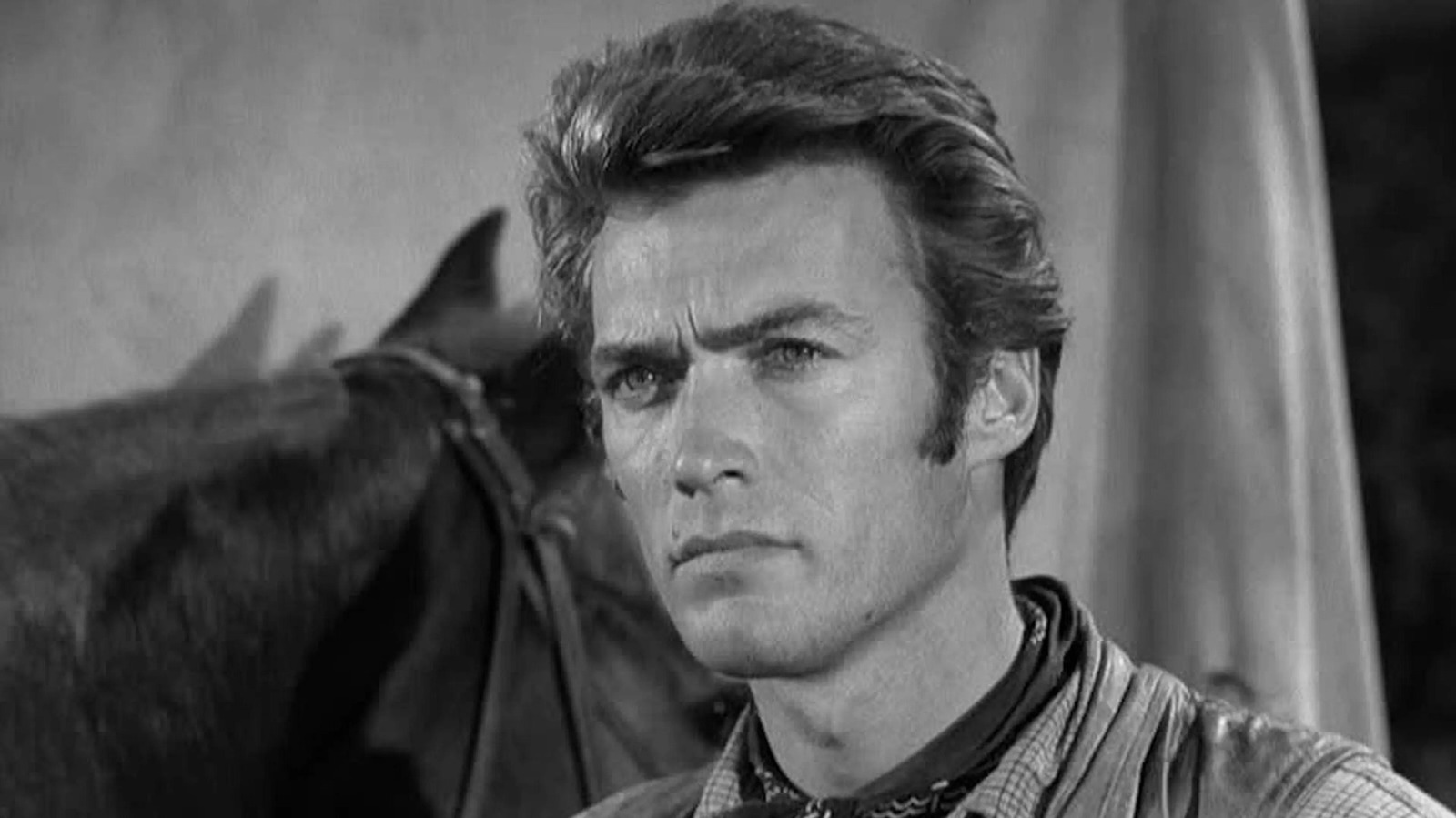

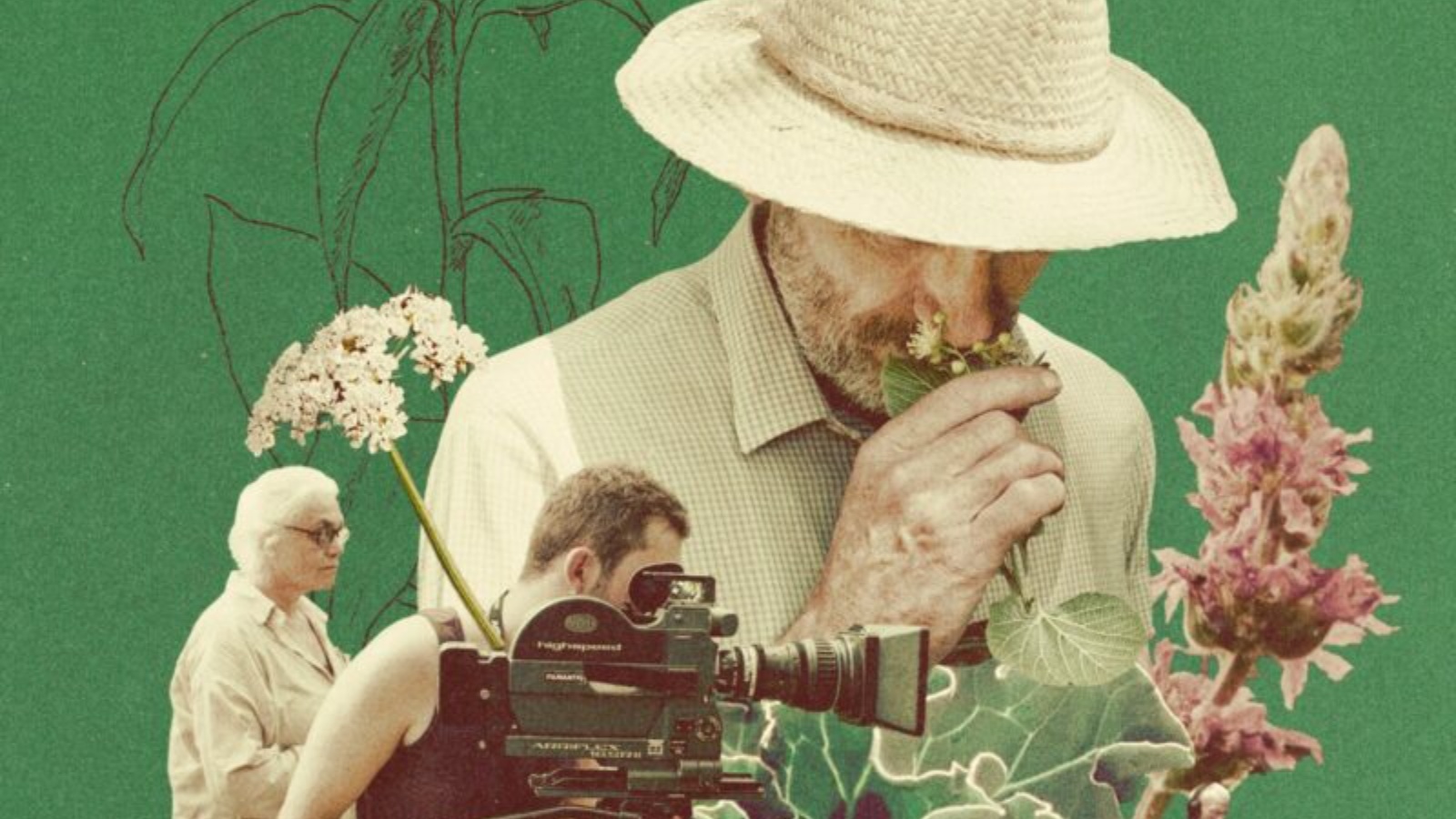

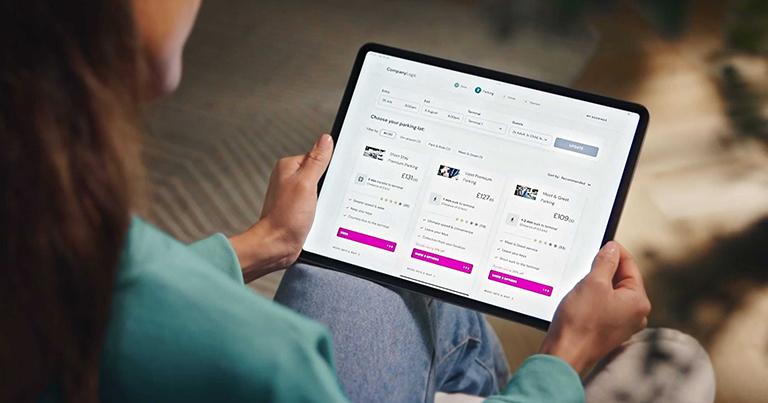

Caught by the Tides (Jia Zhangke, 2024).Jia Zhangke grew up in Fenyang, where the north winds blew cold fronts from Inner Mongolia over the medieval walls. Fenyang is in Shanxi province, China’s coal country, one of the nation’s most polluted regions; when Jia was a child, most of the buildings dated to the Ming and Qing dynasties, and you could bike across town in ten minutes and find yourself in the countryside. His father was a teacher, and his mother worked at the state store that sold liquor and cigarettes; in the 1970s, when food was still rationed by family size, they would send their children to school on a meager breakfast of cornmeal buns. The family all slept in the same bed, and Jia would play in the neighborhood courtyards, surrounded by stone walls. In Walter Salles’s documentary portrait Jia Zhangke, A Guy from Fenyang (2014), Jia returns to his childhood home and slaps the thick walls approvingly: The complex was originally a prison. Later in the film, he visits his mother in a new apartment building and tells her about the trees in their old courtyard. “Just the two apple trees are gone,” he says in her kitchen, a snarl of charging cables plugged into a power strip on a countertop in the background. “It’s sad.… they gave so much fruit.”We are now a quarter of the way through the Chinese Century. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 marked the beginning of its rise to become the dominant political and economic power on the international stage. The country’s status as the world’s largest manufacturing economy and exporter of goods, particularly in the computing and renewable energy sectors, supports its ambitions in development and diplomacy as the United States narrows its horizons. Also in 2001, Jia switched from film to digital and began capturing documentary footage of the locations and people pictured in his fiction films.When Jia’s latest film, Caught By the Tides (2024), premiered at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, he said that it “clos[es] the curtain on this era” of capturing such footage, and perhaps also on the era of China’s rise to remake the geopolitical order. Caught By the Tides is assembled from decades of Jia’s casual documentary footage as well as from outtakes and repurposed scenes from his work beginning with In Public (2001), a short commissioned by the Jeonju International Film Festival and depicting disconnected scenes of everyday life in Datong, Shanxi province. Kevin B. Lee describes In Public as “a location scouting video for” Unknown Pleasures (2002), the feature Jia made in Datong immediately afterward. Portions of the latter film is also reused in Caught By the Tides, as are portions of of Still Life (2006), shot in Fengjie shortly before it was flooded by the Yangtze River after the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, and of Ash Is Purest White (2018), set and shot between Datong and the Three Gorges region across the first decades of the new millennium. The latest filmfollows a couple, Qiao and Bin (played by Zhao Tao and Li Zhubin, who have also played romantically entangled characters in Unknown Pleasures and Still Life), through the upheavals of the turn of the century and through China’s emergence from the COVID-19 pandemic.Caught By the Tides is also a document of Jia and Zhao’s relationship: the two met when the director, casting dancers from Taiyun Teachers College for his second feature, Platform (2000), was taken with their sharp and skeptical instructor. The two have been making this film for the entirety of their life together, as director and actor, artist and muse, and now as husband and wife. Relationships change within Caught By the Tides, as well; characters come together and drift apart, migrate in search of a better future and return home in resignation, only to find the world, and themselves, much changed. The architecture of their hometown is rendered unrecognizable: the old community halls and their tattered banners depicting Chairman Mao have been replaced by supermarkets with shiny floors and abundant winter citruses piled as far as the eye can see. The shock of the new has its reverse-image in the revelation of their own aging, of Zhao’s face, which moviegoers have known since 2000, softening and weathering. Caught by the Tides (Jia Zhangke, 2024).Life is discontinuous, and the film is heterogenous, an impressionistic narrative scrapbooked together from archival footage and new scripted scenes. Qing doesn’t speak in the film; old scenes and loose ends of the character contemplating the world in silence are often reconfigured with post-hoc onscreen text, like silent-movie intertitles. The aspect ratio shifts, often from shot to shot, as Jia cuts between footage captured across more than two decades on the Sony DSR-PD150, Betacam, Sony HDV, the Arri Alexa 35, and even a little 35mm celluloid. Each format, at the time of its introduction, signified new and unprecedented possibilities for realistic image-capture, fro

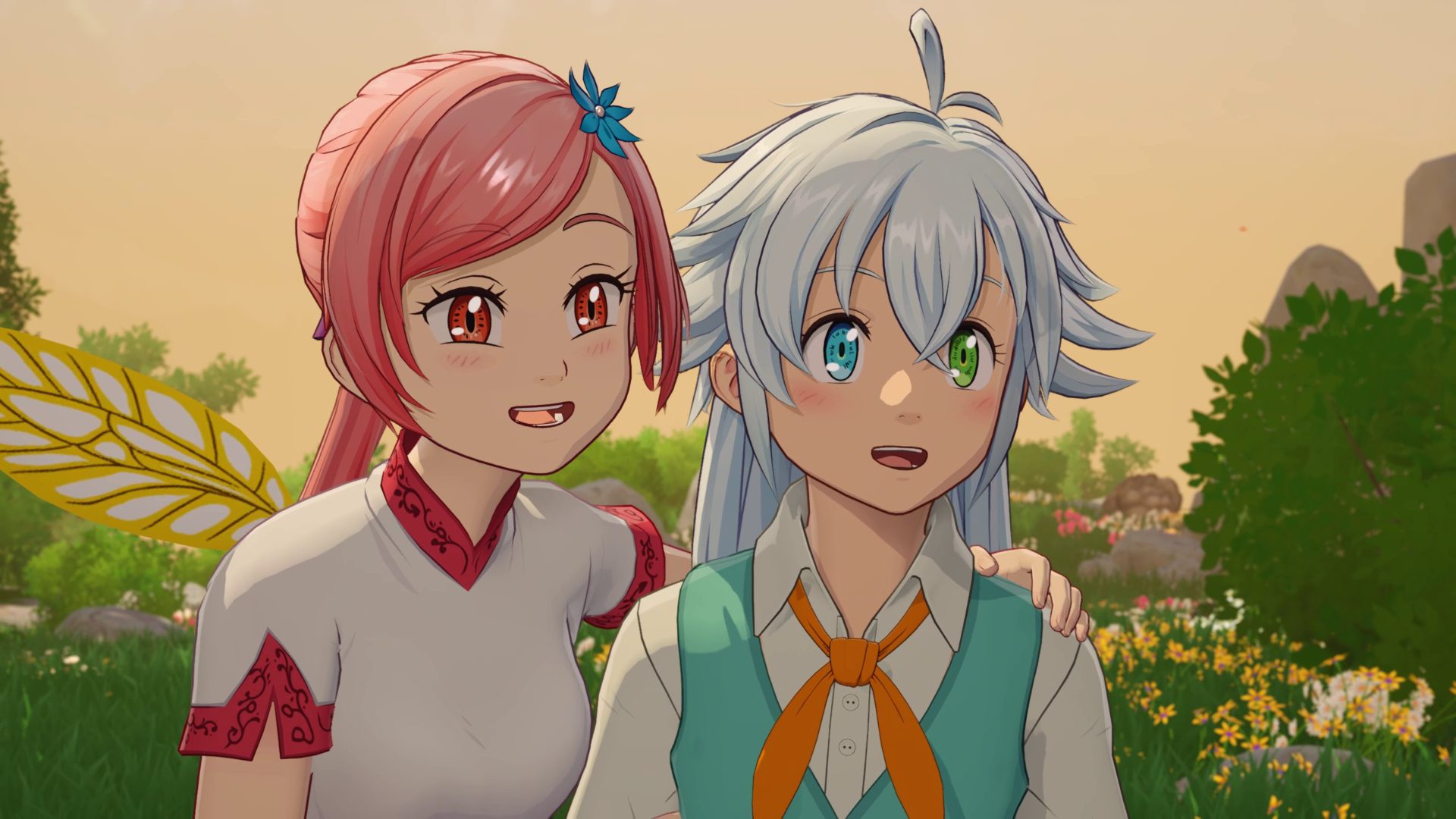

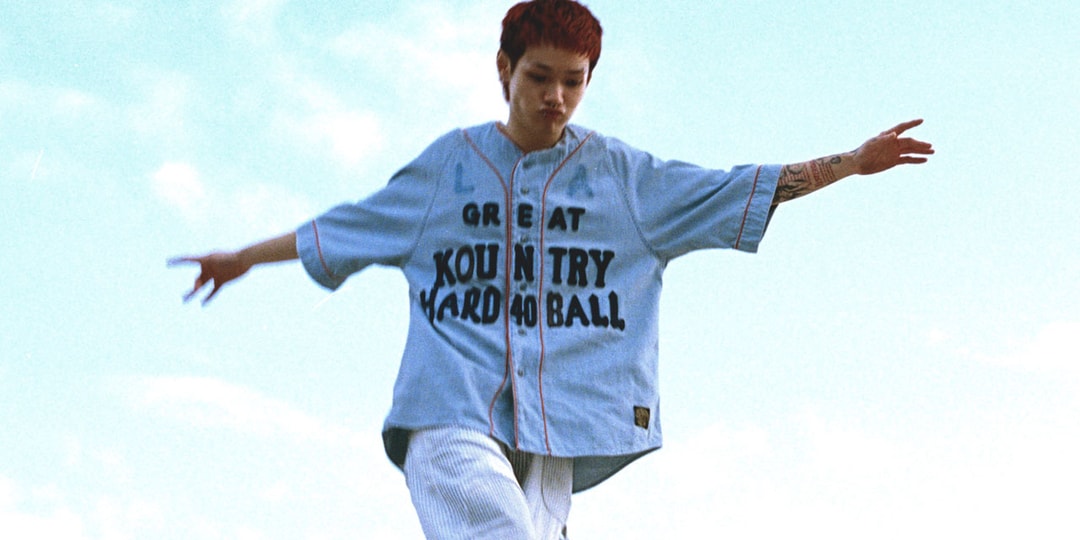

Caught by the Tides (Jia Zhangke, 2024).

Jia Zhangke grew up in Fenyang, where the north winds blew cold fronts from Inner Mongolia over the medieval walls. Fenyang is in Shanxi province, China’s coal country, one of the nation’s most polluted regions; when Jia was a child, most of the buildings dated to the Ming and Qing dynasties, and you could bike across town in ten minutes and find yourself in the countryside. His father was a teacher, and his mother worked at the state store that sold liquor and cigarettes; in the 1970s, when food was still rationed by family size, they would send their children to school on a meager breakfast of cornmeal buns. The family all slept in the same bed, and Jia would play in the neighborhood courtyards, surrounded by stone walls. In Walter Salles’s documentary portrait Jia Zhangke, A Guy from Fenyang (2014), Jia returns to his childhood home and slaps the thick walls approvingly: The complex was originally a prison. Later in the film, he visits his mother in a new apartment building and tells her about the trees in their old courtyard. “Just the two apple trees are gone,” he says in her kitchen, a snarl of charging cables plugged into a power strip on a countertop in the background. “It’s sad.… they gave so much fruit.”

We are now a quarter of the way through the Chinese Century. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 marked the beginning of its rise to become the dominant political and economic power on the international stage. The country’s status as the world’s largest manufacturing economy and exporter of goods, particularly in the computing and renewable energy sectors, supports its ambitions in development and diplomacy as the United States narrows its horizons. Also in 2001, Jia switched from film to digital and began capturing documentary footage of the locations and people pictured in his fiction films.

When Jia’s latest film, Caught By the Tides (2024), premiered at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, he said that it “clos[es] the curtain on this era” of capturing such footage, and perhaps also on the era of China’s rise to remake the geopolitical order. Caught By the Tides is assembled from decades of Jia’s casual documentary footage as well as from outtakes and repurposed scenes from his work beginning with In Public (2001), a short commissioned by the Jeonju International Film Festival and depicting disconnected scenes of everyday life in Datong, Shanxi province. Kevin B. Lee describes In Public as “a location scouting video for” Unknown Pleasures (2002), the feature Jia made in Datong immediately afterward. Portions of the latter film is also reused in Caught By the Tides, as are portions of of Still Life (2006), shot in Fengjie shortly before it was flooded by the Yangtze River after the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, and of Ash Is Purest White (2018), set and shot between Datong and the Three Gorges region across the first decades of the new millennium. The latest filmfollows a couple, Qiao and Bin (played by Zhao Tao and Li Zhubin, who have also played romantically entangled characters in Unknown Pleasures and Still Life), through the upheavals of the turn of the century and through China’s emergence from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Caught By the Tides is also a document of Jia and Zhao’s relationship: the two met when the director, casting dancers from Taiyun Teachers College for his second feature, Platform (2000), was taken with their sharp and skeptical instructor. The two have been making this film for the entirety of their life together, as director and actor, artist and muse, and now as husband and wife. Relationships change within Caught By the Tides, as well; characters come together and drift apart, migrate in search of a better future and return home in resignation, only to find the world, and themselves, much changed. The architecture of their hometown is rendered unrecognizable: the old community halls and their tattered banners depicting Chairman Mao have been replaced by supermarkets with shiny floors and abundant winter citruses piled as far as the eye can see. The shock of the new has its reverse-image in the revelation of their own aging, of Zhao’s face, which moviegoers have known since 2000, softening and weathering.

Caught by the Tides (Jia Zhangke, 2024).

Life is discontinuous, and the film is heterogenous, an impressionistic narrative scrapbooked together from archival footage and new scripted scenes. Qing doesn’t speak in the film; old scenes and loose ends of the character contemplating the world in silence are often reconfigured with post-hoc onscreen text, like silent-movie intertitles. The aspect ratio shifts, often from shot to shot, as Jia cuts between footage captured across more than two decades on the Sony DSR-PD150, Betacam, Sony HDV, the Arri Alexa 35, and even a little 35mm celluloid. Each format, at the time of its introduction, signified new and unprecedented possibilities for realistic image-capture, from the urgency of early camcorder video to the newly cinematic fidelity of HD to the immersive clarity of 4K resolution; juxtaposed with one another here, the effect is of a series of time capsules, each from a different moment along the journey by which Chinese materialism sharpened into focus, from the novel and humble to the dizzying and futuristic.

From the very beginning of his career, Jia’s films were received in the English-speaking film world as the authentic reflection of a changing China; indeed, he made this his explicit subject, line by line and plot by plot. The stories of his characters, caught by the tides of China’s transition from far-flung agrarian communism to the world’s dominant economic and political force, are the story of our time in aggregate.

But just as the cinema of the American century continually redefined itself to reflect a nation’s evolving self-image, the dimensions of the mirror Jia holds up to reality have expanded and warped, in both style and narrative form, from the period marked in Caught By the Tides by quavering DVCAM slice-of-life scenes of peasant women wearing their winter coats indoors, singing old sentimental songs as blown-out white light streams through dirty windows, to the film’s end, with anamorphic widescreen footage of Zhao listening as a customer-service robot recites inspirational quotes.

Jia makes historical films about the times in which he’s lived. Though several of his films span eras, the deepest past he’s ever replicated on film is the decade of his adolescence, the 1980s—defined at the outset by Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, which subsequently saw one of the great historical migrations as a quarter of a billion people moved from the country to the city, populating new high-rise buildings like the one his mother lives in.

What constitutes “realism,” when reality itself has changed so vastly, so comprehensively? The elasticity of the term is the defining quality of Jia’s filmography, which, in telling the story of people living through immense social change, variously reaches for strange effects, formal wooliness, and reflexivity. His films are a canvas stretched across the frame of a world forever in flux.

Jia Zhangke, a Guy from Fenyang (Walter Salles, 2014).

Jia was moved to become a filmmaker after seeing Yellow Earth (1984), Chen Kaige’s drama of feudal tradition on the cusp of the Second Sino-Japanese War. But he soon became disillusioned with China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers—they were “real heroes,” he said early in his career, who “managed to break Chinese cinema out of its closed little mold and try something new. But they’ve changed a lot: In their current films, you’re no longer seeing the experience of life in China. While my way of filming allows me to describe Chinese reality without distortion.” As a student at Beijing Film Academy, he attempted to explore the reality of his experience “without distortion,” in short films like Xiao Shan Going Home (1995), starring his classmate Wang Hongwei as a cook in Beijing navigating various misadventures as he attempts to raise the money for a train ticket back to his rural hometown for the Lunar New Year. Jia’s classmates criticized the film for its use of backward-sounding Shanxi dialect, as opposed to government-standard Mandarin.

Jia had discovered the films of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Michelangelo Antonioni, Vittorio De Sica, and Robert Bresson by the time he himself returned home one New Year, and discovered, he has written, that a local street was slated for demolition, and that “Reform” was forcing his old neighbors “to redefine selves, morals and lifestyles.” Like De Sica in Bicycle Thieves (1948), Jia responded to his fraught time and place with a story of petty crime, shot on location. Xiao Wu (1997) likewise reveals the inspiration of Bresson, revered by Jia for the “purity” of his storytelling, with its spare, focused close-ups of a pickpocket’s nimble fingers at work.

The film “is about the commodification of China,” Jia said in 2003, “with all these new products coming in and infiltrating people’s lives.” An eager convert to the market economy, but one who still makes a living with his hands, Xiao Wu (Wang) is caught between tradition and modernity. On a return to his peasant family’s ancient stone home,he sees his sister singeing the hair off a pig’s head for a fancy dinner while his successful brother hands out imported Marlboro cigarettes.

Deng’s economic reforms began at the dawn of the 1980s with “Special Economic Zones,” port cities where market-driven economic policies were enacted in order to drive foreign investment. Capitalism, in the form of imported goods and newly privatized state enterprises, slowly worked its way inland, to places like Fenyang. Shot on handheld 16mm, with a nonprofessional cast and without permits—using a longer lens for certain exteriors so that the camera could be positioned further away from the actors, to avoid drawing a crowd—Xiao Wu captures raw textures of life: eating around a coal brazier, in a room whose windows are hung with plastic sheeting; bicycles leaning against brick walls in dirt alleyways; piles of rubble everywhere, as if the city is in a permanent state of construction (or demolition). The old and the new sit awkwardly side by side: a novelty lighter plays Beethoven’s “Für Elise” at the tips of cheap Chinese cigarettes. Rejected by his family, Xiao finds a new simulacrum of companionship in the transient urban institution of the karaoke bar, where he strikes up a flirtation with a hostess who presents him with a pager, its every jingle symbolic of a connection that transcends the tightly circumscribed boundaries of the everyday. The film begins and ends with its protagonist on the side of the road, waiting for a ride that will come along and sweep him up into larger historical currents. As the film opens, he’s waiting for a bus into the city center; as it closes, he’s been arrested, and waits in limbo, and in handcuffs, on the Fenyang sidewalk.

Xiao Wu (Jia Zhangke, 1997).

Growing up in Fenyang, Jia was dwarfed by histories and geographies beyond his immediate experience. Once, as a child, he climbed the city walls with his father, then stood atop them in the teeth of a howling wind, looking out at the distant roads and waiting to behold an automobile. In A Guy from Fenyang, he tells Salles that while they were up there, he saw his father cry, a response he only understood years later as a reaction to the knowledge that “on the other side of the wall of the fortified town, there was immense space, an inspiring world that I probably would never know.” Many of Fenyang’s walls were demolished a few years later, as part of Deng’s reforms; when Jia made Platform, inspired by his memories of growing up in Shanxi and dreaming of leaving, he had to shoot in nearby Pingyao, whose walls were still intact.

“The big world is beautiful,” reads a postcard one of the characters sends back home from his first trip to the southern coastal regions around Guangdong province, where some of Deng’s first Special Economic Zones were located. Platform is commensurately bigger and more beautiful than Xiao Wu, shot on 35mm instead of 16mm, but still informed by the tenets of Bazinian realism, with scenes covered in long single takes. The camera is further away, and pans slowly, only ever on a tripod—no dolly tracks—surveying the action dispassionately, almost mournfully.

The film is monumental, spanning the seismic ’80s as the characters, young players in a “Peasant Cultural Brigade” traveling theatrical troupe, follow the fads now leaking into Shanxi from the big cities: Having once performed Maoist propaganda pageants, they eventually evolve into the All-Star Rock and Breakdance Electronic Band. In the opening scenes, Jia films the troupe on stage from the back of the auditorium, the camera at a fixed position at the audience’s eye level, establishing a visual scheme in which the fixed, faraway long takes double as a proscenium, apt for a film that restages recent Chinese history to explain what it was like, just as like as company brings culture, and cohesion, to the masses. Like the mines and factories, the troupe is eventually privatized.

Platform (Jia Zhangke, 2000).

Travel is a motif: After the first performance in the film, during post-show notes that play more like a struggle session, Wang’scharacter, Cui, is criticized for making inaccurate train noises, and defends himself by admitting that he’s never heard one. As a boy, Jia himself once rode his bike ten miles to see a passing train; near the midpoint of Platform, the troupe sees one on their travels, rushing closer to watch it fly by, at once euphoric and bereft as it passes. They caravan across the big, beautiful world, crammed together on buses and tractor beds, on dirt tracks and winding, treacherous—but paved—mountain passes, performing alongside new arterial roads for an audience of fast-moving cars.

Jia, who himself performed with a breakdancing troupe in the 1980s, recalls the revelation of hearing pop music during the Reform era: Young people in Fenyang would strut down the street carrying boomboxes, as the kids in Platform do, dancing maniacally to “Genghis Khan”—a Cantopop cover of a German Eurovision entry, and the first disco song Jia ever heard. He was part of the first generation of Chinese adolescents to grow up with pop music, which replaced the unifying “we” of revolutionary songs with the individuating “I.” Platform, which also tracks the development of Cui’s artistic spirit as it conflicts with the demands of the collective, coincides with the introduction of the One-Child Policy—imposed, in part, to alleviate poverty by giving parents fewer mouths to feed.

Jia’s production design, which relies on locations largely unchanged since the ’80s, tracks public as well as private revolutions: Villages are electrified and streets are paved; one of Hui’s cousins goes down to the mines while the other goes to school. Fortunes diverge and hearts change with fashions: Hair is permed or grown out as the world grows bigger, then smaller again. Couples break up or reform as the actors leave the troupe and return home, one by one. The saddest way that the film measures the passage of time is by the declining crowds the troupe draws to their performances; by the end, even Cui’s mother has a television, which would have been unthinkable a decade prior. Now there’s no need to leave home.

Unknown Pleasures (Jia Shangke, 2002).

Following the historical chronicle of Platform, Unknown Pleasures jumps back into the present tense. Jia’s transition to digital is startling for its anxious intensity. A series of jostling, elaborate handheld following shots traverse the streets of Datong at the speed of a moped, or a nightclub dancefloor at the speed of a raver. The palette is bleached, bright, and brittle. According to Jia, he and Yu, his cinematographer, had been “looking for the beauty in the DV format. I love it because of how suitable it is for the fast-paced shooting we do. I often joke that, if it weren’t for DV, I wouldn’t be able to capture the changes that are happening in China, because they’re so fast!”

Xiao Ji (Wu Qiong), sporting emo-combover bangs and an oversized shirt rippling with cool rockabilly flames, becomes infatuated with Qiao (Zhao), a promotional model and dancer for the Mongolian Kingliquor company, who tuck US dollar bills into bottles. Xiao’s best friend, Bin (Zhao Weiwei), has a girlfriend who’s preparing to study international trade in Beijing; when she needs a break from studying, the two hole up in a video parlor, decompressing from the pressures that the one-child policy has wrought: parental expectations of further education and upward social mobility.

Television is constantly on in the background, reporting on the big world: China’s ascension to the WTO; the announcement of Beijing as the host of the 2008 Olympics; the construction of a new highway that is still unfinished when Xiao picks up Qiao on his scooter and drives her along the road to nowhere. Bin gets a job selling bootleg DVDs; in a cameo, Wang once again plays a character named Xiao Wu, browsing his wares (“I work in finance,” says the former pickpocket, having moved up in the world—he’s now a loan shark). He asks for Xiao Wu and Platform—Jia’s early features, made without Film Bureau permissions and never officially released in China, were hot items on the black market—but settles for a copy of Pulp Fiction (1994). Quentin Tarantino presents something like a design for living for these characters: In a restaurant, Xiao and Qiao avidly narrate the opening stickup scene to each other, Yu’s camera whipping back and forth between them in a frenzy of vicarious excitement, before a smash cut to the club, where Zhao dances like Uma Thurman to a “Miserlou” remix. But when Xiao and Bin finally get the idea to rob a bank, like in an American movie, their escapist delusions run up against their slapstick haplessness and the catastrophic mundanity of their own existence.

The World (Jia Zhangke, 2004).

Jia’s next film, The World (2004), was his first made with state approval. Upon its stateside release, J. Hoberman declared: “China’s leading independent filmmaker—make that China’s leading filmmaker—emerges from the underground only to enter an officially sanctioned virtual reality.” In interviews from the aughts, Jia is consistent in his aspirations to be seen and discussed by large audiences in China, and in The World, also his first film to be shot outside of Shanxi, he found a vertiginous metaphor for the nation contemplating itself on the world stage: Beijing World Park, a theme park that offers the opportunity to “see the world without ever leaving Beijing,” where migrants from the provinces labor as hostesses or construction workers in the shadow of scaled replicas of global landmarks like the Eiffel Tower or the Leaning Tower of Pisa. (So close, yet so far: As Wang’s character in Platform plays a train onstage despite never having heard one, Zhao’s character here dresses up as a flight attendant despite never having been on an airplane.)

This is Jia’s first collaboration with the composer Lim Giong, who did the moody techno scores for Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Goodbye South, Goodbye (1996) and Millennium Mambo (2001), and here provides the music, nervy and lyrical, that accompanies nightly World Park dance performances, pan-ethnic pageants with spurious national costumes and garish flashing lights. The Baudrillardian bubble of The World, the film with which Jia ascended to the status of international spokesperson for modern China, acts as a warning to foreign audiences not to mistake a simulation for the real thing.

If these economically marginal characters are trapped in a liminal departure lounge between a hardscrabble past and a global future, they still get to take flight: Whenever Zhao’s character receives a text message from her romantic interest, Jia dramatizes the exchange with animated interludes, still unique within his filmography, in which the characters soar over the Park’s attractions—a visual rendering of the expanded emotional horizons promised by Xiao Wu’s pager.

Still Life (Jia Zhangke, 2006).

Jia inserts similar touches into Still Life, but they are CG special effects, rather than animation, and depict spaceships, instead of airplanes—an even more surreal flourish, for a film made in an even more symbolically fraught location. The Three Gorges Dam, the world’s largest hydropower station, was conceived by Sun Yat-sen in the early twentieth century, dreamed of by successive governments—the nationalists, the occupying Japanese, the CCP—and constructed between 1994 and 2015, after the displacement of as many as 1.4 million people from the 150,000 acres now submerged by the reservoir. As the region prepared for the flood—nation-building on a Biblical scale—Jia returned to film there on six separate occasions. He gathered footage of the high-water marks spray-painted on the sides of abandoned buildings halfway up the hillsides; the rubble of ongoing demolition; the gaudy lights of the Fengjie Yangtze River Bridge, spanning a deep canyon over a river that would soon rise almost to the level of the roadway; the ferries carrying displaced former residents in one direction past tour boats going the other way, their guides cheerily reciting facts and figures: “By May 1 of 2006, all the houses you see will be underwater.” The film depicts a boom town in reverse: Sledge-swinging migrant workers jump from crew to crew, bringing buildings down rather than building them up; there are brothels, and rival gangs that attack and intimidate each other as local bosses jockey for contracts. Old banners with political slogans and portraits of party leaders are part of the rubble—an archaeological cache for the distant future.

Jia takes inspiration from real locations and films predominantly in long takes, what he calls “the documentary style,” out of frustration with the revolutionary artistic tradition: “After the 1980s and the 1990s, truth has become a very strong aspiration in Chinese art, and that is because we trust in the power to be able to film and to tell what is really happening in China. So I strongly aspired to realism since I started making films.”1 But the “truth” of Still Life is conspicuously poetic, elegiac. Chapter titles—“Cigarettes,” “Liquor,” “Tea”— accompany medium close-ups of abandoned objects, like the still-life compositions alluded to by the English-language title. The world is not found as it is, but arranged into painterly tableaux, and the lateral drift of the camera is slow and dreamy, often lagging behind the movement of the characters to linger on the epic backdrops rather than the human drama unfolding in the foreground. The narrative is loose: Much of the film consists of Jia’s frequent collaborators, Han Sanming and Zhao, wandering in wordless marvelment through space (as Zhao, in Caught By the Tides, would later wander through time). Han—Jia’s cousin—plays a Shanxi coal miner, as he is in life and as he previously played in Platform and The World. He comes to Fengjie—a journey of well over 1,000 kilometers, likely involving some combination of bus, train, and ferry—in search of his wife and daughter, whom he hasn’t seen in sixteen years. Zhao is looking for her husband, whom she hasn’t seen in two. Both reunions are at first deferred, then anticlimactic. Han and his wife have little to say to each other, and his daughter is further south, joining the many who’ve gone on to Guangdong; Zhao’s husband (Li Zhubin again) dodges her calls for days, and when they finally meet, it’s clear they’ve grown apart. She asks him for a divorce as the dam itself looms in the background, endless torrents of water coursing through it.

The scale of these transformations—geographical but also personal—is so cosmic that the transitions between sections of the movie are signaled by spacecraft: a UFO streaks across the sky as the narrative emphasis shifts from Han to Zhao, and a rocket launches in the background shortly before the characters meet. “When I went to look at Fengjie,” Jia said in 2009, “every county we saw had basically been reduced to rubble. Seeing this place, with its 2,000 years of history and dense neighborhoods left in ruins, my first impression was that human beings could not have done this. The changes had occurred so fast and on such a large scale, it was as if a nuclear war or an extraterrestrial had done it.”

24 City (Jia Zhangke, 2008).

Jia had originally come to the Three Gorges region to prepare a documentary, Dong (2006), about Liu Xiaodong, a “documentary painter” attempting to depict the impact of the dam on his neighbors through art. He followed Still Life with 24 City (2008), an oral history of a state-run munitions plant that had been sold off to private developers with plans to demolish it. Talking-head testimonies give the film the appearance of a conventional documentary, but half of them—including one delivered by Zhao, as one of the plant’s former workers—were scripted and fictionalized, a Herzogian “ecstatic truth” befitting a location that went up with the Great Leap Forward and came down to make way for luxury apartments. In I Wish I Knew (2010), a portrait of Shanghai commissioned for the 2010 World Expo, which the city hosted, Jia again sends Zhao wandering through real locations in sequences that sit vaguely between fiction and documentary; these could be scenes from a movie that doesn’t yet exist—another Caught By the Tides—but here, they are the connective tissue between interviews with historical figures who recount their personal and inherited memories of the city from China’s Warlord Era through the Japanese occupation to the Cultural Revolution and the city’s contemporary identity as China’s finance capital. Each era is illustrated with archival film clips of Shanghai, so that the present tense is composed of a dense, variegated, mediated history.

The cinematic nature of modern Chinese life is also the subject of A Touch of Sin (2013), which adapts up-to-the-minute news items, inflected with homages to classic Chinese epic novels and the wuxia films of King Hu. Jia drew on stories that had been ignored by the official media, but spread virally via the alternative discourse platform Weibo, including the tale of a Shanxi miner who, thwarted by bureaucracy, kills the corrupt local official who is hoarding the profits of the privatized, formerly state-run coal mine; a sexually exploited sauna worker, played by Zhao, who stabs an entitled client; and a debt-burdened garment-sweatshop worker in Guangdong who takes his own life.

These stories express moral alarm at the rise of an individualist mindset, manifest in the ubiquity of loan sharks and small-scale extortionists as well as in the larger indulgences of the executive class, and the crisis of average people crushed by the engine of process; the film is an attempt to restore a collective spirit, not least by being a populist spectacle. As Jonathan Rosenbaum and others have pointed out, the four chapters of the film take place at the four corners of China and across the four seasons. The story is panoramic, and individual journeys take on the quality of an odyssey. At the film’s end, Zhao’s character, released from prison, joins the crowd watching an outdoor performance of the classic Chinese opera Yu Tang Chun (once filmed by King Hu), whose repeated lyric “Do you understand your sin?” comments on her own journey, and draws an association between the digital town square of Weibo and older forms of Chinese art.

Jia’s return to fiction was received in some quarters as a shock for its new focus on violence, but the director explained his characters as “ordinary people” who, encountering the violence of society, “go through a transformation”—a phrase that also describes the urbanizing peasants of his earlier films, albeit now with an intensified, “mystical” quality. An anguished state-of-the-nation portrait assembled from sensational and suggestive ripped-from-the-headlines anecdata, the film reflects an era of deepening inequality and extremes of experience, a time when anything feels possible. The tales that result from these circumstances are, inevitably, tall tales.

A Touch of Sin (Jia Zhangke, 2013).

An equivalent period in the American century, and in the American cinema, occurred as the economic boom of the 1920s—characterized by urbanization, financialization, and the mass production of new consumer products—gave way to the Great Depression of the 1930s. The United States underwent mass migrations, away from the Dust Bowl and the Jim Crow South, which remade the country’s demographics. Such wild swings in fortune, and an awareness of the possibility of reinvention in a big country, are reflected in the sound films made in Hollywood before the enforcement of the Hays Code, in which morals are negotiable and characters’ fates rise and fall from pavement to penthouse and back again, and the films’ relationship to genre is equally volatile. In I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), Paul Muni’s character is in turn a war hero, a vagrant and petty thief, an inmate and escapee, a migrant laborer, and a socially prominent architect before becoming an inmate and escapee once more. A film like Three on a Match (1932) has elements of the socially conscious melodrama, the women’s weepie, and the gangster movie. In seemingly every pre-Code film, as in practically every Jia film, there is a crime subplot, a display of entrepreneurial opportunism in an economy where everything is up for grabs, manifested in a bootlegging racket or a stable of bar girls. Jia’s cinema likewise emulates the pre-Code era in the ubiquity of nightclubs as a location—though Jia has never made a musical, Zhao has on multiple occasions played the Shanxi equivalent of a chorus girl, and dance tracks are a constant source of source of hedonic abandon in his films, equivalents of the Jazz Age standards that move the pre-Code melodramas along.

Jia’s next two films are his spin on the “women’s pictures” of twentieth-century Hollywood studios, in which Zhao enacts stories of female endurance across landscapes—emotional, geographic, economic, temporal—so expansive that the films struggle to contain them. It is through such individual stories that economic statistics become comprehensible—even, or perhaps especially, in the stories’ confusion and ambivalence.

Mountains May Depart (Jia Zhangke, 2015).

The story of Mountains May Depart (2015) begins in Fenyang in 1999—so, between the production of Xiao Wu and Platform, and at the outset of Jia and Zhao’s relationship. The film opens to the strains of the Pet Shop Boys’ “Go West” and a New Year’s conga line, with Zhao’s character torn between two lovers, one a miner and one a businessman with a big future ahead of him. He’s just taken the mine private, and by the second section of the film, set in 2014, he’s an investor—living apart from Zhao, by now his ex-wife—and wealthy enough to send their son, called “Dollar,” to a foreign boarding school. In the film’s third section, set in a near-future 2025, Jia imagines his characters flung even further apart by circumstance: Dollar lives in Australia, can barely remember his mother, and speaks so little Chinese that he and his father can only communicate through Google Translate.

Some critics viewed the film, particularly its third section, as awkward—a forced and unnatural departure, as it were, from the mountain-solid observational rigor of Jia’s best work, larded with sprawling speculations about technology, international migration, and spiritual rot, to say nothing of on-the-nose didactic symbolism. (“The dollar’s been in free fall for years—they should have called you Renminbi!”) But melodramatic excess is effective for a film in which a character can set out to make his fortune and become life-alteringly rich in the time elided by a fade to black. The film’s aspect ratio widens with each segment, as the characters spiral ever further away from each other—but one song remains the same. At a crucial moment, customers in an electronic shop test a CD player by putting on a Cantopop ballad, “Take Care,” by Sally Yeh, and the lush orchestration drops into their lives like pennies from heaven. Zhao and Dollar listen to it on an iPad in 2014, and Dollar listens to it on a vinyl record in 2025.

In a recent interview, Zhao declared “Take Care” to be her favorite song: “I still remember the moment when it was played on set during the filming of Mountains May Depart. The feeling that life is unpredictable and full of twists and turns suddenly washed all over me, the feeling that my old friends are all scattered everywhere now.”

Ash Is Purest White (Jia Zhangke, 2018).

In Ash Is Purest White, Zhao is again the constant, shouldering the burden of the plot through a changing society and changing circumstances like a Barbara Stanwyck or a Joan Crawford. It’s another story of a Qiao and a Bin falling in and out of love across time and across China. (This time, Bin is played by Liao Fan.) It opens in turn-of-the-century Datong, where this Bin is a local crime boss and Qiao a gangster’s moll; the first section of the film, a tribute to the Hong Kong gangster films of John Woo, depicts a mad love story amidst factional conflicts. It briefly becomes a woman-in-prison film before jumping ahead to 2006, with Qiao on a boat up the Yangtze, once again looking for Bin in Fengjie. In desperation, she runs a few low-level cons, like a streetwise Joan Blondell–type, before crying through a romantic ballad and admitting it’s over. She rides a train all the way to the Gobi Desert before returning home, closing one chapter of her life and opening another, becoming herself something of a boss in Datong by the time Bin, now frail and diminished, returns for a final, bittersweet reunion.

In both plot and method, the film, fictitious but densely self-referential, is a dry run for Caught By the Tides. Among Eric Gautier’s cinematography, Jia integrates footage Yu shot during the period of In Public and Unknown Pleasures as well as footage of a pre-flood Fenjie circa Still Life; the aspect ratio widens and the shooting format encompasses MiniDV, HD, 2K, 4K, 35mm, and 5-6K. In the final scenes, another Qiao mourns the end of her relationship with another Bin, a scene we witness on the CCTV cameras she’s installed in her gambling den—it’s like the moment in All That Heaven Allows (1955)in which Jane Wyman’s heartbroken face is reflected in the screen of her new television set, only rather than diminished by mass entertainment and narcotized by consumer comforts, Qiao’s pain is enfolded into a matrix of surveillance.

Caught by the Tides (Jia Zhangke, 2024).

It is satisfying to trace a straight line from Jia’s earliest works of dirty-fingernail reportage to the totally synthetic self-pastiche of Caught By the Tides (and beyond: Jia has recently said that he plans to collaborate with artificial intelligence scientists on his next project, because “[AI] makes me rethink film and what changes might be coming”). Caught By the Tides replays memorable scenes from Jia’s career, revisits recurrent themes, and revives characteristic shots. A story of Jia’s ur-couple, it’s something like a collage of the original raw material, one degree removed from reality. But there are elements of this remove throughout his filmography.

Among many other commentators, The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos, in a 2009 profile, declares that, between The World and Still Life, the director “began to grow frustrated with the limitations imposed by realism. He had come to believe that China’s transformations were so fast and mind-bending that putting them on film virtually demanded surrealism.” Either the animations of The World or the spacecraft of Still Life are often posited as a hard swerve away from pure indexicality, to be followed by subsequent, more substantial experiments in form and style. But Jia, the boy from the provinces with a hunger for experience that could only be sated through movies and glimpses of pop culture, has always represented reality in eccentric, multifaceted ways, attempting to grasp and express a context that extends far beyond his frame. From the beginning, his mode was not naturalistic, but supranaturalistic.

Performance is a constant throughout Jia’s films, as is the mediating influence of pop, even in his early, neorealist stuff. Songs overheard by the characters are then taken up by them and repeated throughout their lives. Structured around motifs that recur across his films, swelling, cathartic refrains, his oeuvre depicts everyday life as lyrical. Public loudspeakers are constantly intruding on the foreground of Jia’s sound mix (Xiao Wu’s first sound editor quit rather than have her name attached to it), a constant din of sometimes random and sometimes pointed, warped, distant blurts of news and propaganda, and eventually advertisements and muzak, both the texture of everyday life under the watchful direction of the state, and an ironic commentary on this world as Jia shows it—it’s as if Chinese life itself has a nondiegetic audio track.

Even Xiao Wu ends on a note of metacinematic reflexivity that alludes to the mingled senses of state control, cultural mediation, and destabilizing novelty that contribute to the unreality of modern Chinese life. When Xiao Wu sits by the side of the road in handcuffs, a crowd gathers around him, gawking at the spectacle of his imprisonment. We see the scene—small children, elderly peasants, curious passersby, all gathering in a semicircle, still as a posed portrait, staring curiously, blankly—from Xiao Wu’s point of view. Plainly, these people are actually staring at Jia’s camera. The title card that appears immediately after this final shot—“This entire film is interpreted by non-professional actors”—affirms that we are witnessing them witnessing themselves, reckoning, as they are also, with their new status as subjects of a fiction. Today, the citizens of Fenyang would have their phones out, making a TikTok of Xiao Wu, filming the camera as it films them. From 1997, they stare back at us, observing as the story of their own lives unfolds.

- Cecilia Mello, “Interview with Jia Zhang-ke,” Aniki 1, no. 1 (2014): 344–56. ↩

![‘Jurassic World Evolution 3’ Coming October 21 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/evolution3.jpg)

![‘Dying Light: The Beast’ Arrives August 22 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/thebeast.jpg)

![‘Deadpool VR’ Coming to Meta Quest 3 and 3s Later This Year [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/deadpoolvr.jpg)

![‘Resident Evil Requiem’ Coming February 27; Playable at Gamescom! [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/re9a.jpg)

![Metaphysical Pop [THE MUSIC OF CHANCE]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/the-music-of-chance-patinkin-kid-1.jpeg)

![‘I Don’t Understand You’ Directors Brian Crano & David Joseph Craig On Working With Nick Kroll, Andrew Rannells & Making A Vacation Horror Comedy [Interview]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/06125409/2.jpg)

![United Quietly Revives Solo Flyer Surcharge—Pay More If You Travel Alone [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/united-737-max-9.jpg?#)