Notebook Primer | Med Hondo

The Notebook Primer introduces vital figures, films, genres, and movements in film history.Soleil Ô (Med Hondo, 1970).Historian-Filmmaker, Filmmaker-HistorianMed Hondo’s debut feature, Soleil Ô (1970), concludes with a series of close-up and wide shots of a man screaming, each successive image accompanied by a prolonged, guttural groan. For Hondo, making the film was a form of therapy as he processed his own experiences of racial oppression and alienation as a young African immigrant living in Marseille. Like his contemporaries Ousmane Sembène, Sarah Maldoror, and Safi Faye, Hondo used cinema to interrogate the conditions of immigrant African labor in the metropole. In his expressionist rendering of this eruptive, cathartic scream, Hondo captures a moment of release from the psychological toll of colonization, a prospect Frantz Fanon described in his writings. Here, cinema works to awaken the consciousness of the colonized and plant the seeds of revolution for the liberation of the African continent and diaspora. Hondo recognized that the path forward for an underdeveloped African cinema was emancipation. His films stage a confrontation with the machinations of Euro-American cinema in the battle for Black self-determination. “I have always strived for a cinema of rupture,” Hondo asserts. “I consider that Africans, African civilizations, Black people have their own history, their own destiny, their own expression, and that the cinema they make cannot be the classic cinema made by everybody else.” While cinema has long been used to stabilize Western notions of the self at the expense of “the colonized, the great absentee of history,”1 Hondo put his cinematic project in service of a decolonial and anti-statist praxis of Black liberation, crafting a radical counter-image of the people of the African diaspora as the protagonists of history.Hondo was born in 1936 in Ain Oul Beri Mathar, in the Atar region of Mauritania under the French empire, to a family whose lineage was inter-migratory and culturally nomadic, but ultimately confined by manufactured borders. His father was Senegalese, his mother was Mauritanian, and his paternal grandfather was Malian. On his mother’s side, Hondo was of Haratin ethnic background—a descendant of caste slavery. His maternal grandfather was a slave in Mauritania forced to work for other indigenous Black Africans of higher social classes, whereas his father was a laborer for French elites and was conscripted as a Senegalese tirailleur in the colonial army. His paternal grandfather made a living as a griot, a storyteller. This inheritance of deeply racialized and classed social inferiority and oppression molded a politics of militant Pan-Africanism, honed by tales of resistance passed to him by his elders. In 1956, a young Hondo moved to France as the African nation-states began rapidly decolonizing. He explored theater under the direction of the French actress Françoise Rosay, the widow of Franco-Belgian director Jacques Feyder, which presented various acting opportunities in radio, television, and cinema. Eventually, he secured work as a voice actor, and dubbing African American parts of Hollywood films in French became a crucial source of income that would sustain him even as he ventured into filmmaking. Finding a dearth of dynamic roles for Black actors in the French theater, he and others formed a theater group, Griot-Shango, in Paris. They adapted plays by Black playwrights such as Aimé Césaire, Amiri Baraka, and Daniel Boukman. The underground operating style of his theater troupe would later inform the ways in which his filmic projects approached production, casting, and screenwriting. After seeing Griot-Shango’s production of Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman, Jean-Luc Godard recruited Hondo for an acting role in Masculin féminin (1966). Hondo began writing his first feature screenplay in 1965, which would become a semi-autobiographical, experimental film following a Black African migrant (Robert Liensol) who moves to Paris, the metropole, to pursue self-advancement, a colonially produced pipe dream marketed to those in the former colonies. Instead, he experiences a brutal sequence of structural racism, in forms large and small, which awakens his political consciousness. This film meshes a chaotic mix of cinematic styles and genres (animation, social realism, theatrical acts, absurdist slapstick skits, oral storytelling, documentary, and fiction) to deliver an audacious visual and aural depiction of the everyday horrors of the Black immigrant experience in Europe. Soleil Ô was a success on the festival circuit: It premiered at Cannes, received the Golden Leopard at Locarno, and was well received in New York, Berlin, Tunis, and Ouagadougou. Yet, in France, where Soleil Ô ran for over three months at Paris’s Quintette Theater in 1973, he never received any revenue from its distribution.2 In the United States, however, the film did relatively well at the time of its release, speaking t

The Notebook Primer introduces vital figures, films, genres, and movements in film history.

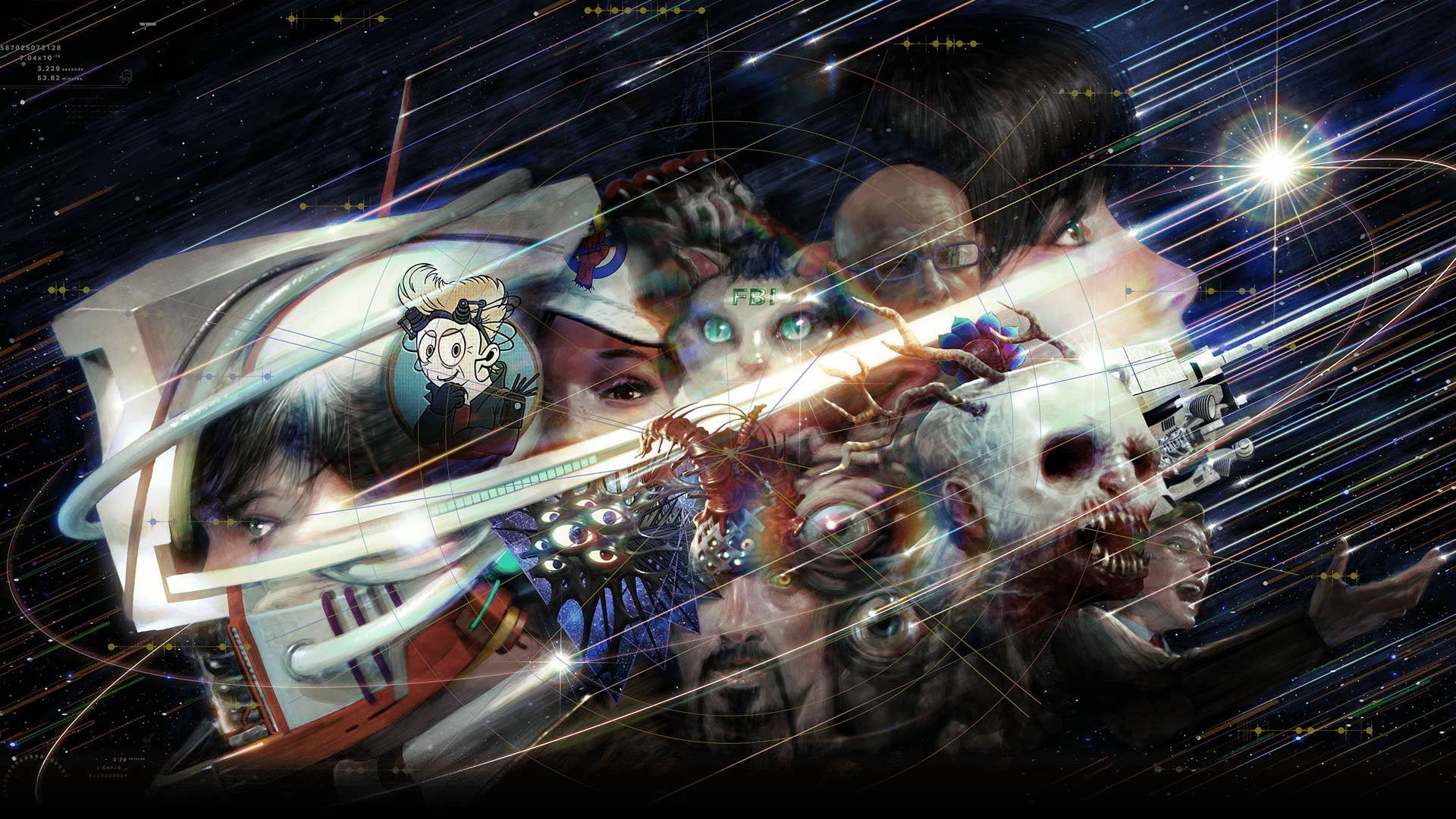

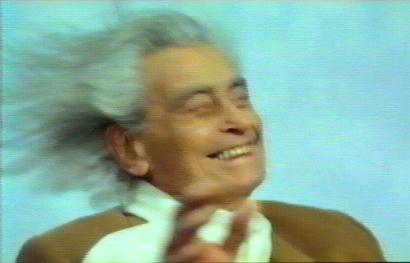

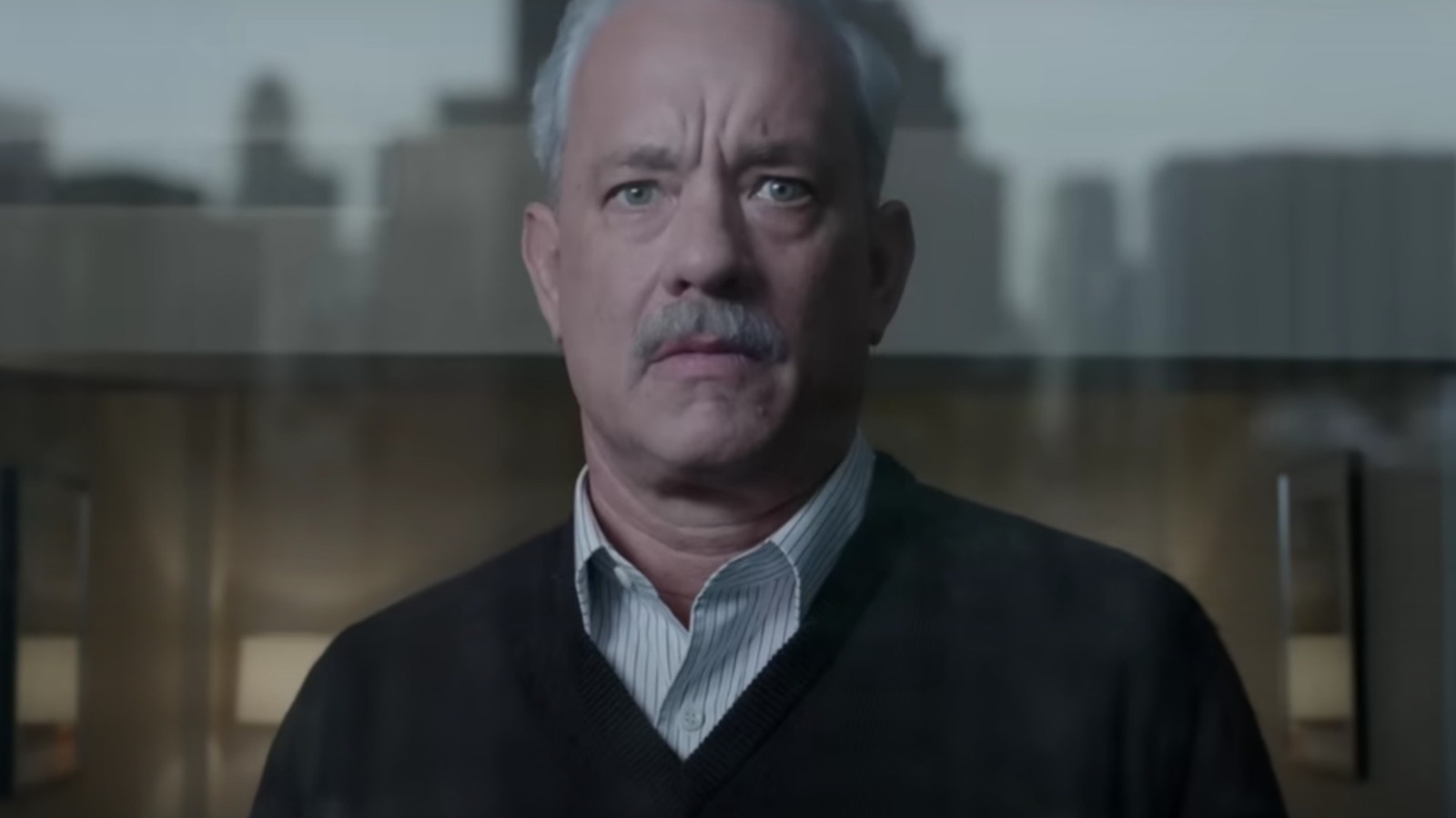

Soleil Ô (Med Hondo, 1970).

Historian-Filmmaker, Filmmaker-Historian

Med Hondo’s debut feature, Soleil Ô (1970), concludes with a series of close-up and wide shots of a man screaming, each successive image accompanied by a prolonged, guttural groan. For Hondo, making the film was a form of therapy as he processed his own experiences of racial oppression and alienation as a young African immigrant living in Marseille. Like his contemporaries Ousmane Sembène, Sarah Maldoror, and Safi Faye, Hondo used cinema to interrogate the conditions of immigrant African labor in the metropole. In his expressionist rendering of this eruptive, cathartic scream, Hondo captures a moment of release from the psychological toll of colonization, a prospect Frantz Fanon described in his writings. Here, cinema works to awaken the consciousness of the colonized and plant the seeds of revolution for the liberation of the African continent and diaspora.

Hondo recognized that the path forward for an underdeveloped African cinema was emancipation. His films stage a confrontation with the machinations of Euro-American cinema in the battle for Black self-determination. “I have always strived for a cinema of rupture,” Hondo asserts. “I consider that Africans, African civilizations, Black people have their own history, their own destiny, their own expression, and that the cinema they make cannot be the classic cinema made by everybody else.” While cinema has long been used to stabilize Western notions of the self at the expense of “the colonized, the great absentee of history,”1 Hondo put his cinematic project in service of a decolonial and anti-statist praxis of Black liberation, crafting a radical counter-image of the people of the African diaspora as the protagonists of history.

Hondo was born in 1936 in Ain Oul Beri Mathar, in the Atar region of Mauritania under the French empire, to a family whose lineage was inter-migratory and culturally nomadic, but ultimately confined by manufactured borders. His father was Senegalese, his mother was Mauritanian, and his paternal grandfather was Malian. On his mother’s side, Hondo was of Haratin ethnic background—a descendant of caste slavery. His maternal grandfather was a slave in Mauritania forced to work for other indigenous Black Africans of higher social classes, whereas his father was a laborer for French elites and was conscripted as a Senegalese tirailleur in the colonial army. His paternal grandfather made a living as a griot, a storyteller. This inheritance of deeply racialized and classed social inferiority and oppression molded a politics of militant Pan-Africanism, honed by tales of resistance passed to him by his elders.

In 1956, a young Hondo moved to France as the African nation-states began rapidly decolonizing. He explored theater under the direction of the French actress Françoise Rosay, the widow of Franco-Belgian director Jacques Feyder, which presented various acting opportunities in radio, television, and cinema. Eventually, he secured work as a voice actor, and dubbing African American parts of Hollywood films in French became a crucial source of income that would sustain him even as he ventured into filmmaking. Finding a dearth of dynamic roles for Black actors in the French theater, he and others formed a theater group, Griot-Shango, in Paris. They adapted plays by Black playwrights such as Aimé Césaire, Amiri Baraka, and Daniel Boukman. The underground operating style of his theater troupe would later inform the ways in which his filmic projects approached production, casting, and screenwriting. After seeing Griot-Shango’s production of Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman, Jean-Luc Godard recruited Hondo for an acting role in Masculin féminin (1966). Hondo began writing his first feature screenplay in 1965, which would become a semi-autobiographical, experimental film following a Black African migrant (Robert Liensol) who moves to Paris, the metropole, to pursue self-advancement, a colonially produced pipe dream marketed to those in the former colonies. Instead, he experiences a brutal sequence of structural racism, in forms large and small, which awakens his political consciousness. This film meshes a chaotic mix of cinematic styles and genres (animation, social realism, theatrical acts, absurdist slapstick skits, oral storytelling, documentary, and fiction) to deliver an audacious visual and aural depiction of the everyday horrors of the Black immigrant experience in Europe. Soleil Ô was a success on the festival circuit: It premiered at Cannes, received the Golden Leopard at Locarno, and was well received in New York, Berlin, Tunis, and Ouagadougou. Yet, in France, where Soleil Ô ran for over three months at Paris’s Quintette Theater in 1973, he never received any revenue from its distribution.2 In the United States, however, the film did relatively well at the time of its release, speaking to a burgeoning Black worker movement.

Polisario, a People in Arms (Med Hondo, 1978).

Cinema as an Archive

As Hondo’s filmic career began ramping up after the success of Soleil Ô, he remained attentive to anti-colonial efforts, developing a transnational solidarity network dedicated to the dream of global Pan-African unity. He frequented Algeria, where he spent time with African National Congress fighters from South Africa, and members of national liberation movements from Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, Angola, Palestine, and Western Sahara.3 He often stayed at the headquarters of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), where he met and offered guidance to Sarah Maldoror, a crucial figure in Pan-African and Lusophone revolutionary cinema.

Elsewhere, too, the anti-imperialist struggles of the Third World were producing new forms of radical cultural production that took on the totalizing systems of colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. The Argentine filmmakers Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas coined the term “Third Cinema” to refer to “the great possibility of constructing a liberated personality with each people as the starting point.”4 Yet many Third Worldist films gravitated toward masculinist, patriarchal, ethnocentric, and nationalistic tendencies, as did many Third World revolutionary struggles. Feminist oppositional films such as Maldoror’s Sambizanga (1972) and Heiny Srour’s The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived (1974) privilege the role of women as fighters and agents of radical change within the revolutionary struggle, work that is often obscured by militant histories.

Between 1974 and 1978, Hondo made his home in the Western Sahara alongside the Saharawi people, who were living under occupation. He made two feature-length documentaries about their struggle for self-determination, political sovereignty, and autonomy over their land. Moroccan and Mauritanian occupying forces were a proxy for Spain to annex territory in the Western Sahara, one of the few former Spanish colonies in Africa. Against them stood the Polisario Front, an ongoing independence movement. Polisario, a People in Arms, a documentary Hondo made for Algerian TV, opens with Sahrawi revolutionary chants and the angelic voice of Toto Bissainthe, a Haitian actress, singer, and a member of the Griot-Shango. She narrates the battles that led to the signing of a historic ceasefire agreement. Rhythmic montages of armed struggle are layered between observational sequences that detail the conditions of the militia and refugees in Algeria, verité-style testimonials from the local community members, interviews with defectors and prisoners of war, and in-depth battlefield reportage.

Throughout the film, special attention is paid to dispelling anti-resistance propaganda. Hondo invites Saharawi prisoners of war—many of whom are Black—to describe the conditions that led them to fight against the Polisario Front and how they ended up in the hands of Polisario fighters. Another scene focuses on an interview with two former French aid workers who were freed in 1976 but have chosen to remain in the Western Sahara, living amongst the Saharawi people. They now understand why the broader populace did not trust them. Later on in the film, a female guerrilla leader explains that aid from colonial powers is often used to create conditions of dependency so that the people can be divided and conquered. From another fighter, we learn that there have been instances of French intelligence operatives disguising themselves as “aid workers.”

Though Hondo does not shy away from depictions of armed resistance and harrowing violence, A People in Arms also provides ample footage of those revolutionary actions that take place off of the battlefield. Saharawi women are highlighted as leaders of political education and protests, caregivers within the refugee camps, as well as fighters in training who will eventually take up arms. The film provides a multiplicitous view of a people under siege: a Spanish language class for young boys ensures the next generations will be able to make the case for self-determination in the colonizer’s tongue; elderly women in the refugee camps weave clothing to offset the wartime hardships. Hondo strikes a balanced portrait of breathtaking visuals of camaraderie, community, and revolution against the horrors of evacuations, guerrilla warfare, and napalm bombings on refugee communities.

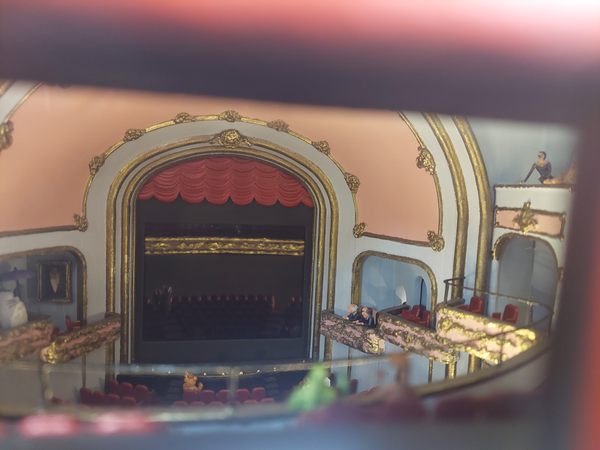

West Indies: The Fugitive Slaves of Liberty (Med Hondo, 1979).

Historical Retellings of Black Refusal

Hondo’s epic musical West Indies: The Fugitive Slaves of Liberty (1979), a Mauritanian-Algerian co-production, is one of the biggest-budgeted African films of that period at $1.3 million (nearly $6 million in today’s money), which includes Hondo’s own contributions from his income as a voice-over actor and a “mound of debt” he had taken on. From the onset, the film was made in opposition to Euro-American monopolies on Black cinema. As Hondo details, “Gaumont Film Company, [a French film and television production and distribution company], was not the film’s distributor, but rather its exploiter. I would have liked that it had been the distributor, for this would have saved me much worry and debts.”5 Major Hollywood studios had also expressed interest in the project, though Hondo rejected their offers when they requested changes to the film’s content.6

Set in an abandoned factory in Paris, staged with a massive replica of a slave ship engraved with “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” across its upper deck, the film is adapted from the play Les négriers by Daniel Bouckman, a Martinican playwright who studied at the Sorbonne, but joined the Algerian revolutionary forces7 rather than be drafted into the French army during the war. Hondo illustrates the ways in which contemporary Black Caribbean migration patterns to France are tied to the political economy of the transatlantic slave trade. The ship literalizes the plundering of resources and bodies from the African continent to the Caribbean, and the factory links these histories to the origins of the Industrial Revolution and modernization in Europe. Caribbean scholar and historian C. L. R. James posits that “the basis of bourgeois wealth [in France] was the slave trade and the slave plantations in the colonies,”8 and this wealth was maintained by overlapping systems of domination. Thus, history moves per the interests of empire and capital.

In the opening title sequence, set to a jazz number, the camera finds an empty seat inscribed with the crest of the French Republic. More chairs appear in front of a map of the Antilles Islands, and one by one they are filled by the deputy head of state, clergy members, a social worker, and the architect of “The Plan”—all of whom are white except for the deputy, La Parlementaire (Robert Liensol), and a missionary officer, Sister Marie Joseph de Cluny (Toto Bissainthe). Propulsive drumming ensues as they congregate to watch an ethnographic film of Afro-Caribbean people working the sugarcane plantations. “These tiny little peoples from these tiny little islands have to vanish from the map,” one of the colonial administrators declares. After the meeting, the theater stage transforms into an arena of ballot boxes. The election is revealed to be a ploy to install a deputy overseer who will look after the colony on behalf of the French state. The island's inhabitants, confined to the ship's lower deck, come above to vote, but obvious ballot stuffing and a 5 p.m. curfew exclude large portions of the working-class electorate. After the election, the colonial elites retreat to the upper deck of the ship to celebrate the win of La Parlementaire. La Parlementaire behaves like a life-size ventriloquist dummy for the French, deluded by the powers bestowed upon him by the sovereign.

In the hold, dissent begins to trouble the social fabric of the colony. Here, Hondo also relies on the architecture of the ship to magnify the racialized and classed dynamics of the different groups, as well as the theater of liberal democracy at play within the colonies under pseudo-independence. Hondo’s subversion of the American musical tradition and French vaudevillian aesthetics comes to life in the choreographed reenactments, playful costuming, and colorful dance numbers, which render 400 years of historical context as it pertains to the Greater and Lesser Antilles, spanning three continents. From the introduction of racialized capitalism through sugarcane production in the French Antilles in 1640; to the slave trade between the West Indies, Africa, Europe, and the Americas; and finally, the government-sponsored emigration campaigns of Caribbean emigrants to France, where they are met with racial subjugation—all is condensed into a two-hour film.

The constantly shifting mise-en-scènes are shaped by musical sequences in a theatrical mode, elaborate set designs, and beautifully constructed long takes. Hondo’s camera is constantly in flux—jumping back and forth between historical periods to showcase vignettes embellished with expressive dance numbers. From the bourgeois balls on the upper decks to the vibrant slave revolts in the hold, each number is layered between a historical epoch and its subsequent electrifying moment of resistance. The figure of the Nègre marrons, enslaved people who escaped the plantations and formed maroon communities on the outskirts of colonial Caribbean society, parallels the young and working-class people on the lower decks who refused to vote in the elections or submit to the emigration campaigns intended to depopulate the island to make way for the tourism industry. At the film’s end, their radical resistance leads to an uprising evocative of the Haitian Revolution.

Sarraounia (Med Hondo, 1986).

Like West Indies, Sarraounia (1986) presents an epic counter-history of anti-colonial struggle. The film began as a coproduction with the Republic of the Niger but the state ultimately withdrew its support, likely influenced by the French government,9 and the Burkinabè revolutionary president (and cinephile) Thomas Sankara stepped in to provide funding. Sarraounia is an adaptation of Abdoulaye Mamani’s novel of the same name, and was developed with Mamani’s guidance; during the research phase, he provided archival material and oral histories. Hondo takes us back to the aftermath of the Berlin conference and the beginnings of the European conquest expeditions on the African continent, focusing on the French colonialists' attempts to invade Niger and the surrounding region of the Sahel in the hopes of introducing a French version of the British Cape-to-Cairo imperial fantasy. Queen Sarraounia of the Azna, the heroine at the center of the story, led a resistance effort in 1899 against the Voulet–Chanoine Mission—a French military expedition sent out from Senegal to Chad and the Congo to conquer large swathes of West Africa.

In the film’s opening, the Gabonese singer Pierre-Claver Akendengué serenades the viewer with beautiful melodies dedicated to the queen of the Azna, Sarraounia. As the film progresses, the score expands to include Akendengué’s musical renditions, Abdoulaye Cisse’s soulful oral storytelling as the film's griot, and kora instrumentals. The film’s musicality fashions a collective sense of yearning for an independent and unified Africa. Shot in low-cost Techniscope and resembling at times the westerns for which that format was often used, amplified by the orange-pink Sahelian dust clouds, Hondo’s Sarraounia scrutinizes settled histories of Western colonial “victories.” The film depicts the grotesque and barbaric imagery of pillaging, rape, massacres, and other genocidal violence at the hands of the French colonial expedition led by Paul Voulet and Julien Chanoine, as well as conscripted colonial soldiers commonly known as the Senegalese Tirailleurs (though not all were Senegalese) under their command and soldiers from the Sokoto Fulani—a largely Islamic pre-colonial empire formed during the Fulani War. Whether center stage or framed in the background, this sadistic violence is always on display.

The titular character (Aï Keïta Yara) is absent from the screen for long stretches of the film, though her spiritual, intellectual, and gallant omnipresence plagues the European invaders and inspires the film’s protagonists to resist. Her appearances are emphasized by Hondo’s straightforward, low-angle camerawork that often presents a larger-than-life figure, playing into allegations that she is a sorceress with supernatural powers. She raises a collective army of Azans, Fulani, Hausa, and other West African communities, boldly organizing across gender, religious, and tribal affiliations. The French invaders are everywhere outsmarted and disgruntled by Queen Sarraounia’s strategic maneuvering, predicated on her profound knowledge of the Sahelian landscape.

In the film’s stunning final sequence, Sarraounia and her army are in retreat, but the colonial forces begin to implode due to their greed and grand imperial fantasies, and a mutiny erupts among the Senegalese Tirailleurs. It is a counter-discursive revision of the historical records of the Battle of Lougou, by which the French fortified their colonial narratives of victory over and pacification of the native population. The film ends just before the long-awaited battle, but Hondo offers an alternative: a statuesque Sarraounia delivers a galvanizing and unifying speech to her large army of African women and men—mostly peasants, nomads, and working-class people. “We have different languages and beliefs, but we all have the same desire to be free,” she exclaims in Bambara. Hondo offers an audacious lesson in Pan-Africanist political education: To adequately examine the events of the present, one must look to the great leaders of our past. Sarraounia’s story is not unique; there have been other African women leaders in the fight against colonialism: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita of the Congo, Ranavalona in Madagascar, Nzinga Ana de Sousa Mbande in Angola, Aline Sitoé Diatta in Senegal, and many more. Despite winning the Grand Prize at FESPACO in 1987, the film was a commercial failure due to continued state censorship and a limited release in France. This caused quite a stir within French and African filmmaking communities, causing major figures such as Jacques Demy, Sembène, Costa-Gavras, Souleymane Cissé, Paulin Vieyra, Bertrand Tavernier, Louis Marcorelles, and Ignacio Ramonet to come together and petition for its proper distribution.

Fatima, the Algerian Woman of Dakar (Med Hondo, 2004).

Cinema and Underdevelopment

Embedded in Hondo’s filmic language is a rewriting of state-sanctioned narratives. He interrogates the collective amnesia around colonial-era abuses, including those committed by colonized subjects. This comes to a head in Hondo’s final film, Fatima, The Algerian Woman of Dakar (2004), which opens in modern Senegal with a cautionary message from a griot (Thierno Ndiaye Doss): “Our past is ours, our present is uncertain, and our future is bleak, but there is only one Africa. … Heal Africa’s wounds.” Cut to 1957, a black-and-white Algeria. Fatima (Amel Djemel), an Amazigh woman, hides in the shadows of the Aurès Mountains as a column of the French colonial army terrorizes the Algerian countryside to quell the national liberation struggle. A Senegalese sub-lieutenant, Souleyman, (Aboubacar Sadikh Ba), finds Fatima and rapes her, unwittingly impregnating her.

The story is based on true events told to Hondo by Tahar Cheriaa, a Tunisian film critic and founder of the Carthage Film Festival. During the Algerian War, conscripted colonial soldiers were deployed to North African colonies to suppress liberation movements. Frantz Fanon details this practice: “Whenever there has been any attempt at insurrection, the military authorities ordered only the colored soldiers into action. It is the men of color who annihilated the attempts at liberation by other men of color.”10 The film brings these injustices to light, inviting audiences to reflect on the complexities of the past.

Fatima is compelled to marry her rapist, per her Islamic and cultural convictions, and she finds her version of happiness in Senegal with Souleyman and their growing family. This surprising turn of events does not obscure the social, patriarchal, and religious pressures Fatima faces throughout the film, especially toward the end, when Souleyman seeks out a second wife against her wishes. Yet, cushioned between the traumas of war, sexual violence, and patriarchal antagonisms within Islamic societies, a unified Africa emerges through contentious paths of repair, reconciliation, and healing. Like Sarraounia, Fatima is an agent for an emancipatory and Pan-Africanist vision of liberation, though her story also serves as an inward look at a fractured Africa, riven by colonial borders and racialized divisions. Homages to Frantz Fanon, Cheikh Anta Diop, Che Guevara, Kateb Yacine, and Omar Blondin Diop create the sense of an anti-colonial tour, for which Hondo credits filmmakers Djibril Diop Mambéty and Ababacar Samb-Makharam as inspirations. Even the score is a tribute to the post-independence Senegalese music scene.

West Indies: The Fugitive Slaves of Liberty (Med Hondo, 1979).

Like Sembène, Hondo was never satisfied with the idea of cinema as mere entertainment; for both, it was a tool of political education for the masses. These filmmakers, towering figures in shaping African cinema, sought to put cinema in conversation with history and collective memory: battlefields on which the struggle for national liberation is fought. Ultimately, as Yasmina Price has written of Sembène, “being a filmmaker was a call to arms,” and that call was in service of an emancipatory vision of a truly autonomous Africa encompassing the entire diaspora. Hondo materialized that vision by empowering a diasporic network of filmmakers, cultural workers, activists, critics, and intellectuals.

Both the Pan-African Film Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO) and the Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI) aim to establish an internationalist ecology of cinema distribution outside the dominant Euro-American production and distribution networks. Hondo helped to shape the missions and identities of these organizations on a world stage through his groundbreaking text, “What Is Cinema for Us?,” as well as his cultural organizing efforts. Within FEPACI, Hondo helped to create the Comité Africain des Cinéastes (CAC) and release Sembène’s anti-war film The Camp at Thiaroye (1988) in Paris.

Hondo dreamed of making a film about the leader of the Haitian Revolution, titled Toussaint Louverture, the First of the Blacks, but continued censorship and funding problems made it impossible to fulfill his last wish before his death in 2019. Together, Hondo’s thirteen films represent a constant battle against mechanisms of control and profit entrenched in the mainstream film industry. By delivering to screens stories that are absent or misrepresented within Western cinema—stories foregrounded in collective memory, West African orality, and the richness of African and Afro-diasporic histories, cultures, and resistance—Hondo envisioned a militant and borderless cinema to counter the violences of the colonial archives and Hollywood hegemony

- Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism (Paris: Maspero, 1959; English trans., New York: Grove Press, 1967), 39. ↩

- Aboubakar Sanogo, “Soleil Ô: “I Bring You Greetings from Africa,” October 1, 2020 ↩

- On the Run: Perspectives on the Cinema of Med Hondo, At the Algerian Cinematheque, pg. 157 (Berlin: Archive Books, 2021) ↩

- Fernando Solanas and Octavia Getino, “Towards a Third Cinema,” Tricontinental (1969): 107–132. ↩

- Med Hondo, “With Reference to West Indies: Les nègres marrons de la liberté: critique of a critique,” On the Run: Perspectives on the Cinema of Med Hondo (Berlin: Archive Books, 2021), 89. ↩

- Hondo, “With Reference to West Indies, 90 ↩

- Astrid Kusser Ferreira, “‘This ship will sink!’ : Politics of memory and Afro-diasporic ontology in Med Hondo’s West Indies: Les nègres marrons de la liberté, On the Run: Perspectives on the Cinema of Med Hondo, (Berlin: Archive Books, 2021), 66. ↩

- C. L. R. James (as J. R. Johnson), “The Revolution and the Negro,” New International (December 1939), 339–43. ↩

- Aboubakar Sanogo, “By Any Means Necessary: Med Hondo,” Film Comment (May–June 2020). ↩

- Frantz Fanon, “The So-Called Dependency Complex of Colonized Peoples,” in Black Skin, White Masks (Pluto Press: 2008 [1952]), 77. ↩

![The Sweet Cheat [THE PAST REGAINED]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/timeregained-womanonstairs.png)

-0-8-screenshot.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)