Head-On: A Conversation with Takashi Miike

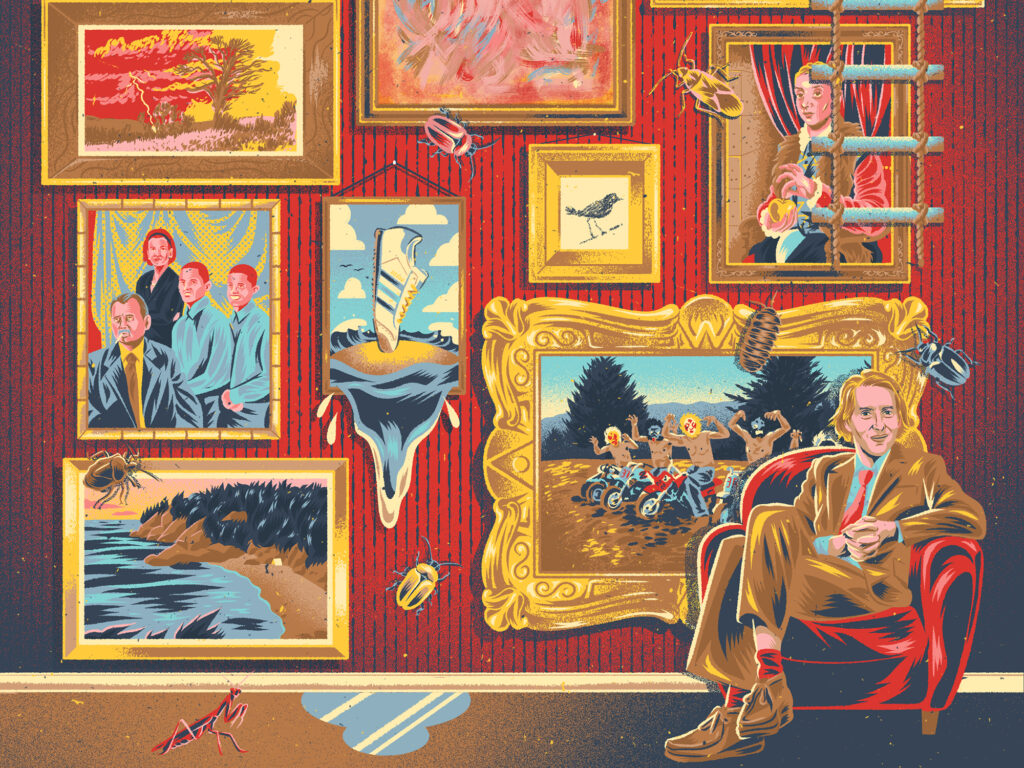

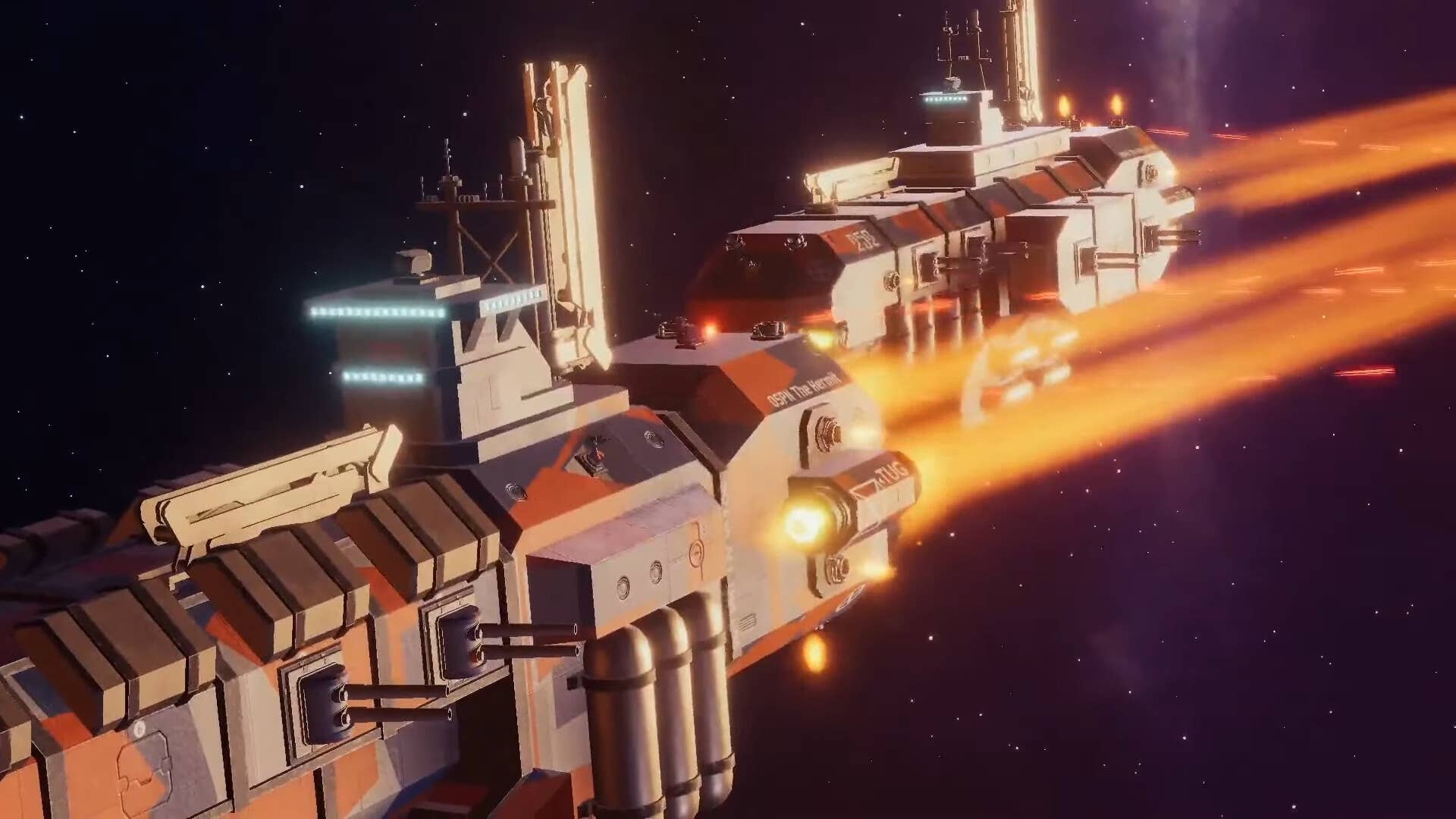

Blazing Fists (Takashi Miike, 2025).With over a hundred films and three decades of filmmaking work under his belt, there are myriad ways in which one can introduce Takashi Miike. To many, he’s the uncompromising provocateur behind Audition (1999) and Ichi the Killer (2001)—audacious gambits that helped usher in a new wave of international interest in Japanese genre cinema. To domestic audiences, he’s a prolific director-for-hire of blockbuster entertainment, helming everything from popular anime adaptations to fantasy-adventure films for children. To obsessive completionists and scholars, he’s a key figure of V-cinema, and a director who brings into focus the human and the interpersonal, crafting performance-driven character dramas such as Gozu (2003), The Bird People in China (1998), and Dead or Alive 2: Birds (2000). He’s a renowned action director, a surrealist, and he’s mastered jidaigeki (period dramas) to boot.Miike’s latest film, Blazing Fists (2025), was inspired by the autobiography of MMA fighter Mikuru Asakura, who appears in the film as a mentor figure to the protagonists. Miike and screenwriter Shin Kibayashi have crafted an archetypal tale of brotherly rivalry, hand-to-hand combat, lies, gangs, and friendship. With an electrifying energy to its kinetic, impactful violence, Blazing Fists operates in a similar mode to First Love (2019).The evening before I’m due to speak with Miike, he takes to the stage at International Film Festival Rotterdam, accompanied by regular producer Misako Saka, for a talk with Patrick Frater. Their conversation plays the hits to a charmed audience: Audition and its feminist readings, Ichi the Killer and its urban legend of nauseating festival-goers, Miike’s jidaigeki collaborations with British film producer Jeremy Thomas in 13 Assassins (2010), Hara-kiri (2011), and Blade of the Immortal (2017). The director engages these topics with a warm smile, but one gets the sense that he has long departed these shores. These were, after all, many projects ago.Changing with the times, the veteran filmmaker has diversified his output beyond feature films. He made his Korean-language debut in 2022 with the Disney+ drama serial Connect. He served as chief director on a CG anime adaptation of the PlayStation 2 game Onimusha for Netflix in 2023, a project which featured the facial likeness of Toshiro Mifune. Unbeknownst to most Western viewers, he directed a string of magical girl tokusatsu series for TV Tokyo (Girls x Heroine) from 2017 to 2022. Later this year, his chief director credit will appear in Nyaight of the Living Cat, a Crunchyroll original anime about an epidemic that transforms humans into felines.This is also a time of great change for Japan’s film industry, which faced an overdue #MeToo reckoning in 2022. Industry figures responded by rethinking their approach to production. One such initiative that emerged is K2 Pictures, a film fund launched at Cannes last year that seeks to break away from the traditional conservative production committee system. Blazing Fists is one of the first films produced with K2 Pictures’ involvement. Miike’s recently announced projects include two English-language features: a production with Charli XCX and a Tokyo-set Bad Lieutenant offshoot. Our conversation delves into production contexts past and present as we consider a career that is always in motion.Ichi the Killer (Takashi Miike, 2001).NOTEBOOK: Blazing Fists is loosely inspired by a sports autobiography. What attracted you to the project?TAKASHI MIIKE: There’s a martial art that’s really catching on right now in Japan—especially among young people, and particularly among dropouts. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a professional or an amateur—even if you’ve never trained in martial arts, if you’re naturally good in a fight, you can join. It’s all about figuring out who’s the strongest.This competition uses a format known as “Open Finger.” Participants wear a special finger guard, and there are professional referees to ensure the bout isn’t dangerous. In just one minute, the match is decided. Because it only lasts one minute, even those without extensive training can participate. Professional fighters sometimes join too, and every now and then they even lose—proving that in a one-minute bout, raw fighting ability can sometimes outmatch formal training.It’s incredibly popular because young people — eager to change their tomorrow even just a little—come together in the midst of a reality that often seems unchanging. The idea for this film emerged from the people who take part in these tournaments. There’s a clearly defined audience, so it’s a very enjoyable project.NOTEBOOK: What stands out to me in a great number of your films is the theme of brotherhood. You often have two characters as opposing forces, opposites. I think of films like Ichi the Killer, the Dead or Alive trilogy [1999–2002], and indeed Blazing Fists. These characters fight each other, but equally find themselves draw

Blazing Fists (Takashi Miike, 2025).

With over a hundred films and three decades of filmmaking work under his belt, there are myriad ways in which one can introduce Takashi Miike. To many, he’s the uncompromising provocateur behind Audition (1999) and Ichi the Killer (2001)—audacious gambits that helped usher in a new wave of international interest in Japanese genre cinema. To domestic audiences, he’s a prolific director-for-hire of blockbuster entertainment, helming everything from popular anime adaptations to fantasy-adventure films for children. To obsessive completionists and scholars, he’s a key figure of V-cinema, and a director who brings into focus the human and the interpersonal, crafting performance-driven character dramas such as Gozu (2003), The Bird People in China (1998), and Dead or Alive 2: Birds (2000). He’s a renowned action director, a surrealist, and he’s mastered jidaigeki (period dramas) to boot.

Miike’s latest film, Blazing Fists (2025), was inspired by the autobiography of MMA fighter Mikuru Asakura, who appears in the film as a mentor figure to the protagonists. Miike and screenwriter Shin Kibayashi have crafted an archetypal tale of brotherly rivalry, hand-to-hand combat, lies, gangs, and friendship. With an electrifying energy to its kinetic, impactful violence, Blazing Fists operates in a similar mode to First Love (2019).

The evening before I’m due to speak with Miike, he takes to the stage at International Film Festival Rotterdam, accompanied by regular producer Misako Saka, for a talk with Patrick Frater. Their conversation plays the hits to a charmed audience: Audition and its feminist readings, Ichi the Killer and its urban legend of nauseating festival-goers, Miike’s jidaigeki collaborations with British film producer Jeremy Thomas in 13 Assassins (2010), Hara-kiri (2011), and Blade of the Immortal (2017). The director engages these topics with a warm smile, but one gets the sense that he has long departed these shores. These were, after all, many projects ago.

Changing with the times, the veteran filmmaker has diversified his output beyond feature films. He made his Korean-language debut in 2022 with the Disney+ drama serial Connect. He served as chief director on a CG anime adaptation of the PlayStation 2 game Onimusha for Netflix in 2023, a project which featured the facial likeness of Toshiro Mifune. Unbeknownst to most Western viewers, he directed a string of magical girl tokusatsu series for TV Tokyo (Girls x Heroine) from 2017 to 2022. Later this year, his chief director credit will appear in Nyaight of the Living Cat, a Crunchyroll original anime about an epidemic that transforms humans into felines.

This is also a time of great change for Japan’s film industry, which faced an overdue #MeToo reckoning in 2022. Industry figures responded by rethinking their approach to production. One such initiative that emerged is K2 Pictures, a film fund launched at Cannes last year that seeks to break away from the traditional conservative production committee system. Blazing Fists is one of the first films produced with K2 Pictures’ involvement. Miike’s recently announced projects include two English-language features: a production with Charli XCX and a Tokyo-set Bad Lieutenant offshoot. Our conversation delves into production contexts past and present as we consider a career that is always in motion.

Ichi the Killer (Takashi Miike, 2001).

NOTEBOOK: Blazing Fists is loosely inspired by a sports autobiography. What attracted you to the project?

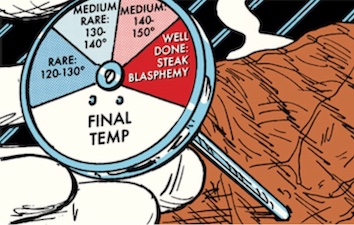

TAKASHI MIIKE: There’s a martial art that’s really catching on right now in Japan—especially among young people, and particularly among dropouts. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a professional or an amateur—even if you’ve never trained in martial arts, if you’re naturally good in a fight, you can join. It’s all about figuring out who’s the strongest.

This competition uses a format known as “Open Finger.” Participants wear a special finger guard, and there are professional referees to ensure the bout isn’t dangerous. In just one minute, the match is decided. Because it only lasts one minute, even those without extensive training can participate. Professional fighters sometimes join too, and every now and then they even lose—proving that in a one-minute bout, raw fighting ability can sometimes outmatch formal training.

It’s incredibly popular because young people — eager to change their tomorrow even just a little—come together in the midst of a reality that often seems unchanging. The idea for this film emerged from the people who take part in these tournaments. There’s a clearly defined audience, so it’s a very enjoyable project.

NOTEBOOK: What stands out to me in a great number of your films is the theme of brotherhood. You often have two characters as opposing forces, opposites. I think of films like Ichi the Killer, the Dead or Alive trilogy [1999–2002], and indeed Blazing Fists. These characters fight each other, but equally find themselves drawn to each other with strong bonds. It’s as if these men are magnets. What interests you about these opposing pairs?

MIIKE: When a person tries to live true to themselves, they are bound to encounter an enemy.

I believe that by clashing with that presence and struggling against it, a person begins to shine even brighter.

NOTEBOOK: Some of your films culminate in an erotic union of sorts between the two men. I think of the ending of Dead or Alive: Final [2002], where Riki Takeuchi and Sho Aikawa fuse into a single, phallic mecha, or the climax of Gozu, where protagonist Minami has sex with a genderswapped version of his yakuza brother, which causes the male version to emerge from her genitals. Later, you'd make explicitly gay films such as Big Bang Love, Juvenile A (2006). Were you consciously making queer-inflected films, and what do these elements in your work mean to you?

MIIKE: Well, it's not so much a social statement—in those days, that kind of movement hadn’t really taken off yet—but it would seem unnatural if such characters didn’t appear. In our works, especially in those low-budget projects, there are very few taboos or topics that are absolutely off-limits to portray. Of course, there are some issues—religious matters and various other things—that are considered forbidden. But for me, it’s not about adding something just to give the film a unique flavor. It’s more that, naturally, there are people like this; there are characters who exist, and that’s completely normal. Depending on who’s playing the role, you might get the sense that, deep down, the character has been hiding it all along—that he likes men. When planning out such roles, deciding on costumes and all that, if an idea strikes me, I just try to incorporate it as honestly as possible.

Audition (Takashi Miike, 1999).

NOTEBOOK: Just as the ways in which your works are read by audiences have perhaps shifted, the environment in which that work is produced is shifting also. It’s of course an interesting time of change in the Japanese film industry. The #MeToo moment in 2022 prompted industry introspection, and directors such as yourself and Yukihiko Tsutsumi have been making moves to break away from the traditional committee system of production.

MIIKE: If I don’t express agreement with [the #MeToo] trend, people might think I’m out of touch with the times, but personally, I’m not that interested. I think that true diversity and liberation don’t come from trying to overcome issues solely through laws, social norms, or external pressure. Cinema should embody this spirit by creating films that defy current trends, that go against the grain to shock audiences and spark debate. Such counter-cultural works, born naturally rather than forced by a predetermined theme, are what truly serve as effective entertainment.

In Japan, directors who have used violent, authoritarian tactics—those who exploit their overwhelming authority as directors to be harsh on their staff or actresses, effectively undermining human rights through their methods—have all lost work and have been socially ostracized. That’s only natural, and in many ways they’ve brought it upon themselves. Still, it’s hard to imagine what the state of things will be once this global trend settles down.

NOTEBOOK: You’ve always been prolific in your film output, but in recent years you’ve been decidedly more eclectic with the type of content that you've made and produced. Has it been a conscious or strategic move to diversify?

MIIKE: Working with such dynamic, energetic people is incredibly exciting. Back in the day, our senior filmmakers were obsessed with film—it was common sense until just twenty or thirty years ago that movies had to be shot on film. But now we can recreate the unique qualities of film digitally, and that gap is closing fast. We can even use CGI to achieve a resolution that, while not perfect, surpasses that of traditional filmmaking. So, when I see these people at work, I think that, while we must still hold on to what truly matters, our focus should shift. It’s not just about the medium—it’s about what tools we use, how we shoot, how we distribute, and how we reach our audience. We need to pursue the content itself, its inherent entertainment value, our own unique vision, and the interesting ideas that drive us.

This shift isn’t just a deliberate choice on my part—it reflects a gradual change in the industry’s balance of power. I try not to resist that change too much, instead embracing the evolving environment.

Connect (Takashi Miike, 2022).

NOTEBOOK: Your Disney+ series Connect is Korean-language. Hirokazu Koreeda, similarly, made Broker [2022] in Korea. It strikes me also that these new streaming series have worldwide distribution and a greater reach. Do you have an international audience in mind during the creative process?

MIIKE: I found the reactions of the Korean actors and crew, as well as the situations and outcomes born from my presence as a sort of “foreign element,” to be genuinely fascinating and enjoyable. Whether in Korea or Japan, I’m always more conscious of the people I create the work with than of the audience.

NOTEBOOK: You've been active and prolific for over three decades. To many people, you are contemporary Japanese genre cinema. What does the weight of that brand feel like, and what keeps you interested in continuing to make new work?

MIIKE: I haven’t been working with the goal of being prolific. That has come from a steady accumulation, one project at a time. Since I’ve created works across various genres, I’m sure different viewers have their own preferences and dislikes. I’ve simply faced each piece head-on, without fear of failure or of betraying expectations. That’s how I intend to continue. I don’t concern myself with building a brand. If I had to sum up my driving force in one word, it would be curiosity.

Under what circumstances can a veteran, as they grow older, still create something truly interesting? Moving forward, my work should serve as a source of encouragement for both those who have built a career and retired, and young people—conveying the message "There's more to come for you, too!" You don't necessarily have to embed that message directly into your work. If you keep doing what you do, your work, along with that message, will naturally resonate.

The author wishes to thank Kanako Fujita for translating, and Keiko Yoshida of GAGA and Elizabeth Prado of the IFFR Press Team for facilitating this conversation.

![Wriggling Free of Perfection [THE EEL]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/theeel.jpg)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)