Cannes 2025 | One Moment

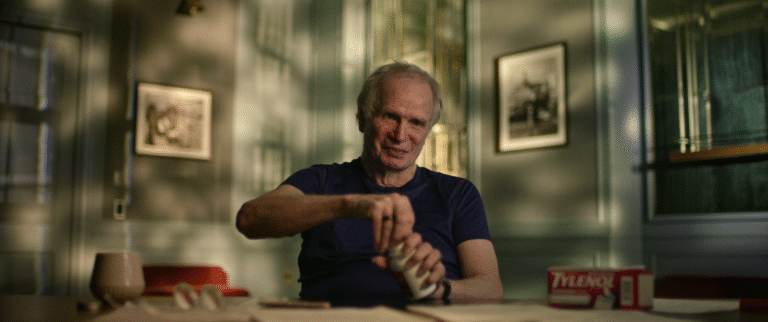

Illustration by Franz Lang.We asked some of the finest critics stalking the Croisette to tell us just one moment from this year’s festival that they won’t soon forget.Vadim RizovBefore every official competition screening at Cannes since 1991, the same computer-generated bumper has been shown. As described by former festival head Gilles Jacob, this ascent over red stairs from watery depths “starts at the bottom of the ocean, rises above the waves, and ends up among the stars—where the Palme d’Or belongs.” During round-number anniversary years, directors’ names are added to the stairs, but this year they’re blank. If you’re feeling uncharitable, this can serve as a damning metaphor for the festival itself: an image created in 1991 synecdochally standing for a selection of bedrock auteurs that remain stuck in the same time period. If you’re feeling charitable, the metaphor is more positive: the future of Cannes is unwritten, and the best is yet to come.Beatrice LoayzaIt was pouring—the kind of torrential rain that makes umbrellas useless—as I made my way to an early screening of Julia Ducournau's Alpha. My expectations were low. I hated Titane, which had won the Palme d'Or in 2021, and now I was seeing her latest body horror in soggy jeans. The A/C was blasting and I was frigid, while the heavy precipitation pelleted the roof of the Agnès Varda theater throughout the film. The soundscape was bracing, which, compounded with the heightened sensations of my own still-drying body, made me perhaps more attuned to the film's vulnerability and grace. (Who could have believed it after Titane’s attention-baiting slickness?) The film reimagines the years of the AIDS epidemic, trading out body horror's conventionally gory imagery for a kind of sickness rendered in marble and stone: at one point, the protagonist's mother, a doctor, takes samples from the chalky, crumbling back of her malady-stricken brother, accidentally hitting the equivalent of a nerve and releasing a stream of red powder. The moment startled me; blood, guts, and viscera, I was used to, but a craggy physique signals a loss of control that's more primitive, elemental. Outside, the downpour continued. Inney PrakashThe highlight of my Cannes was meeting and interviewing 87 year old filmmaker T’Ang Shushen, whose splendid 1968 film The Arch—which apparently played at the very first Director’s Fortnight, though it’s missing from their website—premiered in a new restoration in Cannes Classics. After making four features in Hong Kong, she became (and remains) a restaurateur in Los Angeles. When I informed her I worked for The Asia Society, she exclaimed, “Oh! I do a lot of catering business with them!”Resurrection (Bi Gan, 2025).Mark Asch“If dreams are like movies,” sings Adam Duritz, of Counting Crows, in the song “Mrs. Potter's Lullaby,” from the band’s 1999 album, This Desert Life, “then memories are films about ghosts.” Bi Gan’s Resurrection is a film about ghosts, memories, and dreams that are like movies. I cannot possibly claim to have unraveled all or even very many of its mysteries at a 10 p.m. press screening on Day 10 of the festival after [redacted] glasses of rosé at the finest Lebanese restaurant in Cannes, which delves into a century of Chinese cinema as a lone future dreamer gropes his way through murky and garbled memories of Shanghai noir, the Fifth Generation ’80s, and the turn of the 21st century. During the last-named sequence, which unfolds in a half-hour single take traversing a city-as-set and jumping in and out of multiple points of view, you can detect the sound of Smile.dk's “Butterfly,” last heard at Cannes just twelve months ago, in Jia Zhangke's similarishly reflexive and era-spanning Chinese cinematic odyssey Caught By the Tides (2024). Sitting up there in the Debussy balcony with my equally punch-drunk friends, I felt myself caught up in the slipstream of many histories at once: the cinema’s, the festival’s, my own. All thanks to Bi Gan's lullaby.Nicolas RapoldSome might say it’s indulgent to see the same film twice at Cannes, where time is at a premium and newer premieres always beckon—but not when that film is Resurrection. Bi Gan’s stunning portmanteau work overwhelmed me on a first viewing in one of the festival’s ludicrous post-22:00 slots, which tend to dump one bleary-eyed onto the sidewalk. But it was actually the second screening on the following morning that left me truly walking on air: It was as if I’d dreamt the film’s gorgeous journey the night before, and then had the privilege of revisiting that dream and exploring its world at leisure, tearing up with emotion.Leonardo GoiBi Gan’s sprawling journey through dreams and cinema, Resurrection, culminates in a long, unbroken take that has become something of a signature move for the 35-year-old director. An hourlong uninterrupted 3D sequence encompasses the entire second half of his previous feature, Long Day’s Journey into Night (2018). Clocking in at 40 minutes or s

Illustration by Franz Lang.

We asked some of the finest critics stalking the Croisette to tell us just one moment from this year’s festival that they won’t soon forget.

Vadim Rizov

Before every official competition screening at Cannes since 1991, the same computer-generated bumper has been shown. As described by former festival head Gilles Jacob, this ascent over red stairs from watery depths “starts at the bottom of the ocean, rises above the waves, and ends up among the stars—where the Palme d’Or belongs.” During round-number anniversary years, directors’ names are added to the stairs, but this year they’re blank. If you’re feeling uncharitable, this can serve as a damning metaphor for the festival itself: an image created in 1991 synecdochally standing for a selection of bedrock auteurs that remain stuck in the same time period. If you’re feeling charitable, the metaphor is more positive: the future of Cannes is unwritten, and the best is yet to come.

Beatrice Loayza

It was pouring—the kind of torrential rain that makes umbrellas useless—as I made my way to an early screening of Julia Ducournau's Alpha. My expectations were low. I hated Titane, which had won the Palme d'Or in 2021, and now I was seeing her latest body horror in soggy jeans. The A/C was blasting and I was frigid, while the heavy precipitation pelleted the roof of the Agnès Varda theater throughout the film. The soundscape was bracing, which, compounded with the heightened sensations of my own still-drying body, made me perhaps more attuned to the film's vulnerability and grace. (Who could have believed it after Titane’s attention-baiting slickness?) The film reimagines the years of the AIDS epidemic, trading out body horror's conventionally gory imagery for a kind of sickness rendered in marble and stone: at one point, the protagonist's mother, a doctor, takes samples from the chalky, crumbling back of her malady-stricken brother, accidentally hitting the equivalent of a nerve and releasing a stream of red powder. The moment startled me; blood, guts, and viscera, I was used to, but a craggy physique signals a loss of control that's more primitive, elemental. Outside, the downpour continued.

Inney Prakash

The highlight of my Cannes was meeting and interviewing 87 year old filmmaker T’Ang Shushen, whose splendid 1968 film The Arch—which apparently played at the very first Director’s Fortnight, though it’s missing from their website—premiered in a new restoration in Cannes Classics. After making four features in Hong Kong, she became (and remains) a restaurateur in Los Angeles. When I informed her I worked for The Asia Society, she exclaimed, “Oh! I do a lot of catering business with them!”

Resurrection (Bi Gan, 2025).

Mark Asch

“If dreams are like movies,” sings Adam Duritz, of Counting Crows, in the song “Mrs. Potter's Lullaby,” from the band’s 1999 album, This Desert Life, “then memories are films about ghosts.” Bi Gan’s Resurrection is a film about ghosts, memories, and dreams that are like movies. I cannot possibly claim to have unraveled all or even very many of its mysteries at a 10 p.m. press screening on Day 10 of the festival after [redacted] glasses of rosé at the finest Lebanese restaurant in Cannes, which delves into a century of Chinese cinema as a lone future dreamer gropes his way through murky and garbled memories of Shanghai noir, the Fifth Generation ’80s, and the turn of the 21st century. During the last-named sequence, which unfolds in a half-hour single take traversing a city-as-set and jumping in and out of multiple points of view, you can detect the sound of Smile.dk's “Butterfly,” last heard at Cannes just twelve months ago, in Jia Zhangke's similarishly reflexive and era-spanning Chinese cinematic odyssey Caught By the Tides (2024). Sitting up there in the Debussy balcony with my equally punch-drunk friends, I felt myself caught up in the slipstream of many histories at once: the cinema’s, the festival’s, my own. All thanks to Bi Gan's lullaby.

Nicolas Rapold

Some might say it’s indulgent to see the same film twice at Cannes, where time is at a premium and newer premieres always beckon—but not when that film is Resurrection. Bi Gan’s stunning portmanteau work overwhelmed me on a first viewing in one of the festival’s ludicrous post-22:00 slots, which tend to dump one bleary-eyed onto the sidewalk. But it was actually the second screening on the following morning that left me truly walking on air: It was as if I’d dreamt the film’s gorgeous journey the night before, and then had the privilege of revisiting that dream and exploring its world at leisure, tearing up with emotion.

Leonardo Goi

Bi Gan’s sprawling journey through dreams and cinema, Resurrection, culminates in a long, unbroken take that has become something of a signature move for the 35-year-old director. An hourlong uninterrupted 3D sequence encompasses the entire second half of his previous feature, Long Day’s Journey into Night (2018). Clocking in at 40 minutes or so, Resurrection’s oner is a lot shorter but no less spellbinding, following two young lovers through a maze of caliginous alleyways and ending with a voracious kiss-cum-bite on a barge at sunrise. As the first beams of light pierce the mist, refracting over the river on which the boat is floating, I remember holding my breath; it was the closest the festival came to a moment of transcendence. Someone in my late-night Debussy screening clapped, and continued doing so for a while; I don’t blame them. Though cinema can be an agonizing art form, films like this remind you of its capacity to conjure the sublime.

Sirât (Óliver Laxe, 2025).

Daniella Shreir

There were several watery films by women in this year’s Official Selection. For the protagonists of Love Me Tender, Sound of Falling, Romería, and The Chronology of Water, seas, lakes and swimming pools are sites of trauma, salvation and self-discovery. At the arid (and, in my opinion, showily male) end of the spectrum was a film I disliked, but which nevertheless got under my skin: Oliver Laxe’s Sirât. Aside from the muddy swamp that constitutes the first physical and interpersonal challenge for the film’s traveling protagonists, Sirât is totally devoid of moisture: Its setting is a desert. The film follows a group of European ravers, plus a father and his young son, whose quest is not one of pleasure. The former, skin leathery and hair matted by wind and dirt—habitués of the Moroccan desert—subsist on a seemingly endless supply of tobacco and psychedelics. Until the film’s final sequences, when a character announces that it is about to run out, the question of drinking water is absent from the script. This only occurred to me during the scene which ended up being my favorite. After his father makes him a back-of-the-van dinner, the child asks if there’s dessert. In response, the father produces an orange and a bar of chocolate, which the son asks to share with the ravers. His father tries to deter him with reference to their meagre rations, but has no convincing moral arguments. Implicit in his words is one of the contradictions of parenting: Yes, I taught you to share, but there are exceptions to that rule. Not long after this moment, the film goes off track, or takes a path that I found to be a betrayal. I hoped that it would stay with the ideas it touches upon here: the negotiation between blood and “chosen family”, and the crushing of ideals by a harsh environment that is—as Laxe intends it—also our world.

Elena Lazic

The mood on the final day of the Cannes Film Festival, reserved for catching up with competition films, is always particular. Suddenly, the city is largely emptied of familiar faces, replaced with tourists in flip flops; goodbyes have already been said, there are no new films to collectively discover, and the stimulating conversations that occupied our days are replaced with sometimes depressingly clinical debates about who will win which award. This limbo between the frenzy of festival days and the quieter pace of the everyday lives to which we will soon return can be a rather lonely time, and I was feeling a little fragile at 8:30 a.m. for the screening of Óliver Laxe’s Sirât in the Palais.

That peculiar atmosphere turned out to be the ideal setting in which to watch this film, named after the path or bridge that connects hell and paradise. Like Sergi López’s Luis, I felt myself stranded between the pleasant hum of a repetitive routine and the moment-to-moment intensity of an extreme experience. Like him, I felt both the relaxing sensation of sunshine on my skin and the kind of physical exhaustion that can derail one’s thoughts. But while Sirât begins with and mostly focuses on his ordeal, as an outsider who joins a group of ravers on their travels, the film also captures beautiful moments of sympathy between strangers, and the bond formed during shared adventures.

It was during one such scene of connection that, all of a sudden, the lights of the Debussy came on, the sound turned off, and after a few seconds the screen went dark. As the packed cinema erupted in disapproving shouts (certain spectators seemed to believe that those in the projection booth needed to be alerted that the film had stopped) but also sarcastic applause, the audience found itself in a peculiar collective experience of its own. I can’t deny that I was at first rather scared: Incredibly shocking moments in the film itself had not exactly soothed those preexisting feelings of vulnerability, and neither had the heavily armed troops parading down the Croisette every day, in fact. But once WhatsApp confirmed that this interruption resulted from a region-wide power cut, I began to enjoy the sense of camaraderie in the room. The fact that there were only a few walkouts suggested that most people, like me, were enjoying the film and eager to see how it ended. Strangers started to make conversation in a way they surely wouldn’t have otherwise, and when the lights went down again a few minutes later—the Palais, it turns out, has its own generator—the applause was that of a recharged audience eager to brave together the rest of Laxe’s brain-melting, body-moving trip of a film.

Daniel Kasman

The image that remains burned in my mind is from Lav Diaz’s Magellan, the Filipino director's audaciously sprawling and splintered story of the sixteenth-century colonizing explorer. It is an image we see repeated often in different contexts, yet the base horror remains the same. Bodies are strewn about the frame, the bloody end of a battle we did not see. Composed in direct lineage with John Ford’s and Straub-Huillet’s severe precision and tense use of deep space, and photographed and colored by Artur Tort (Pacifiction, 2022; Afternoons of Solitude, 2024) in hotly hallucinogenic hues, the scene is not a resplendent “period film” recreation but instead taps into the land’s psyche and exhumes anguish. Where Europe intersects with these Pacific islands, murder is found. The feeling is desolate, devastated. We arrive after the fight, when mostly death remains—death, and the conqueror.

Continue reading our coverage of Cannes 2025.

![‘Elden Ring Nightreign’ Receives New Trailers Ahead of Friday Launch [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/eldenringnightreign.jpg)

![Chains Of Ignorance [NIGHTJOHN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/nightjohn2.jpg)

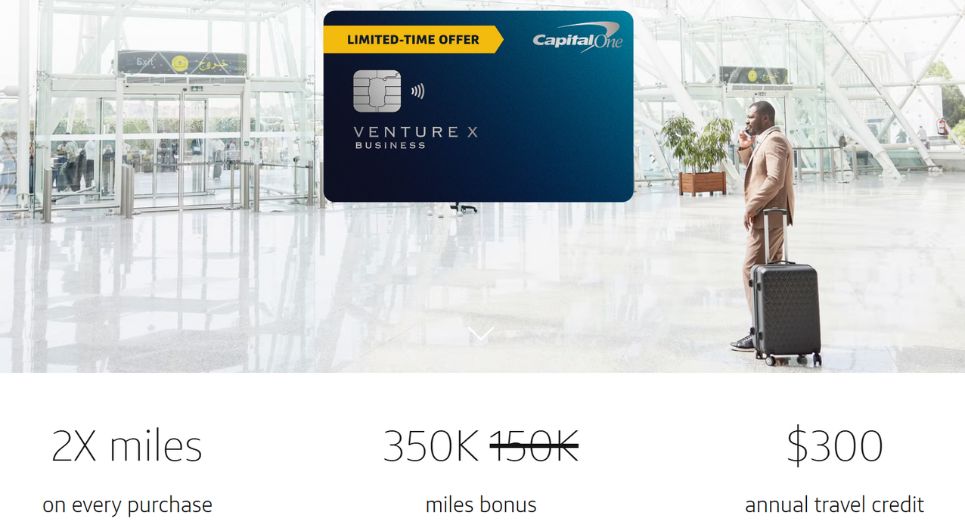

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)