Cannes 2025 | Power to the People

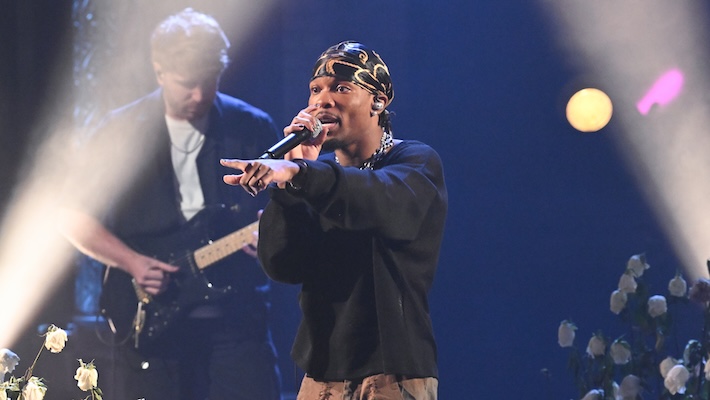

Illustration by Franz Lang.No official competition title unveiled in Cannes this year spoke to our troubled times with the same full-throated urgency as Jafar Panahi’s Palme d’Or–winning It Was Just an Accident (all titles 2025 unless otherwise noted). It was a historic award for a groundbreaking film. Panahi, who had already received the Golden Lion in Venice for The Circle (2000) and the Golden Bear in Berlin for Taxi (2015), joins Henri-Georges Clouzot, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Robert Altman as one of the four directors to have won top honors at all three festivals. And he completed the trifecta with a film that serves as an explicit, fearless response to the censorship and humiliations he has long suffered at the hands of the regime in his native Iran. In July 2022, the filmmaker was arrested by Iranian authorities for signing a petition against police violence, and subsequently spent several months in jail. It was only the latest in a long series of legal battles with the regime, which in 2010 found him guilty of peddling propaganda against the state, sentenced him to six years in prison, and barred him from making films for twenty. None of this actually stopped him, and the several features he has completed since—from his chronicle of a day under house arrest, This Is Not a Film (2011) to No Bears (2022), in which he stars as a director stuck in Iran but overseeing a long-distance shoot in neighboring Turkey—all addressed his predicament. But his latest feels like the project he has spent his entire career working toward; it’s his fiercest, loudest cry for justice yet. In It Was Just an Accident, four Iranians who did time for protesting the regime manage to track and abduct the officer responsible for the atrocities they suffered behind bars. They knock him unconscious, shove him inside a minivan, and drive around debating what to do—exact their revenge, or forgive and set him free? This excruciating dilemma anchors the film, and it is a testament to Panahi’s humanism that Accident should steer clear of polemics or vindictive messaging. The regime’s minions are devastated by its workings, along with its victims, and Accident’s moral ambivalence is Panahi’s greatest achievement. The film operates in a much less experimental register than some of its forebears. Reportedly shot without a permit around Tehran—and starring actresses who do not wear the mandatory hijab, a first—Accident is a kind of chamber play, and there’s a stage-like quality to some of its sequences entirely unlike the rest of Panahi’s filmography. But Amin Jafari’s unobtrusive camerawork and the long takes with which Panahi captures some of the most incendiary exchanges give his cast a chance to flex their skills, and their characters’ debates burst with a harrowing, life-or-death energy. As Panahi smiled atop the stage of the Grand Auditorium Lumière, I wondered what would happen to him next. After all, he was in France only because Iranian authorities had allowed him to attend, lifting a travel ban that had kept him away from the Croisette for the last fifteen years. Where his fellow countryman Mohammad Rasoulof refused to return home after the Cannes premiere of his The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024), Panahi returned to Tehran two days after the awards ceremony, greeted by chants of “woman, life, freedom” as he ambled through the airport. There’s no telling how the regime will react to the film, or what new measures it may take against its director, but there was something almost cosmic about seeing Panahi accept a prize for a work that amounted to an act of artistic catharsis. At any rate, Accident was by no means the only official competition entry to sponge some of the insurgent spirit and acrid anger that swept across the festival. Sergei Loznitsa’s USSR-set Two Prosecutors, a bleak reworking of Costa-Gavras’s Z (1969), tracks a young prosecutor’s pursuit to bring Stalin’s secret police to justice; Dominik Moll’s Case 137 homes in on an internal investigation into police abuse during the 2018 Yellow Vest protests in France; and in The Secret Agent, Kleber Mendonça Filho (awarded the Palme for Best Director), follows a university researcher who turns against the military dictatorship in 1970s Brazil. Top: It Was Just an Accident (Jafar Panahi, 2025). Bottom: Heads or Tails (Alessio Rigo de Righi and Matteo Zoppis, 2025).Such rebellious fervor echoed from other sidebars as well. Heads or Tails, an Un Certain Regard standout, chronicles its own David-versus-Goliath fight. A freewheeling western set in post-unification Italy, Alessio Rigo de Righi and Matteo Zoppis’s latest probes the nexus between stories and myths—where the former becomes the latter, and how they endure. This is nothing exactly novel for the Italian duo, whose oeuvre has long been enchanted by the act of telling. Their first foray into fiction, The Tale of King Crab (2021), is a Russian doll of tales within tales: the story of a gangly drifter who flees his nat

Illustration by Franz Lang.

No official competition title unveiled in Cannes this year spoke to our troubled times with the same full-throated urgency as Jafar Panahi’s Palme d’Or–winning It Was Just an Accident (all titles 2025 unless otherwise noted). It was a historic award for a groundbreaking film. Panahi, who had already received the Golden Lion in Venice for The Circle (2000) and the Golden Bear in Berlin for Taxi (2015), joins Henri-Georges Clouzot, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Robert Altman as one of the four directors to have won top honors at all three festivals. And he completed the trifecta with a film that serves as an explicit, fearless response to the censorship and humiliations he has long suffered at the hands of the regime in his native Iran.

In July 2022, the filmmaker was arrested by Iranian authorities for signing a petition against police violence, and subsequently spent several months in jail. It was only the latest in a long series of legal battles with the regime, which in 2010 found him guilty of peddling propaganda against the state, sentenced him to six years in prison, and barred him from making films for twenty. None of this actually stopped him, and the several features he has completed since—from his chronicle of a day under house arrest, This Is Not a Film (2011) to No Bears (2022), in which he stars as a director stuck in Iran but overseeing a long-distance shoot in neighboring Turkey—all addressed his predicament. But his latest feels like the project he has spent his entire career working toward; it’s his fiercest, loudest cry for justice yet.

In It Was Just an Accident, four Iranians who did time for protesting the regime manage to track and abduct the officer responsible for the atrocities they suffered behind bars. They knock him unconscious, shove him inside a minivan, and drive around debating what to do—exact their revenge, or forgive and set him free? This excruciating dilemma anchors the film, and it is a testament to Panahi’s humanism that Accident should steer clear of polemics or vindictive messaging. The regime’s minions are devastated by its workings, along with its victims, and Accident’s moral ambivalence is Panahi’s greatest achievement. The film operates in a much less experimental register than some of its forebears. Reportedly shot without a permit around Tehran—and starring actresses who do not wear the mandatory hijab, a first—Accident is a kind of chamber play, and there’s a stage-like quality to some of its sequences entirely unlike the rest of Panahi’s filmography. But Amin Jafari’s unobtrusive camerawork and the long takes with which Panahi captures some of the most incendiary exchanges give his cast a chance to flex their skills, and their characters’ debates burst with a harrowing, life-or-death energy.

As Panahi smiled atop the stage of the Grand Auditorium Lumière, I wondered what would happen to him next. After all, he was in France only because Iranian authorities had allowed him to attend, lifting a travel ban that had kept him away from the Croisette for the last fifteen years. Where his fellow countryman Mohammad Rasoulof refused to return home after the Cannes premiere of his The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024), Panahi returned to Tehran two days after the awards ceremony, greeted by chants of “woman, life, freedom” as he ambled through the airport. There’s no telling how the regime will react to the film, or what new measures it may take against its director, but there was something almost cosmic about seeing Panahi accept a prize for a work that amounted to an act of artistic catharsis. At any rate, Accident was by no means the only official competition entry to sponge some of the insurgent spirit and acrid anger that swept across the festival. Sergei Loznitsa’s USSR-set Two Prosecutors, a bleak reworking of Costa-Gavras’s Z (1969), tracks a young prosecutor’s pursuit to bring Stalin’s secret police to justice; Dominik Moll’s Case 137 homes in on an internal investigation into police abuse during the 2018 Yellow Vest protests in France; and in The Secret Agent, Kleber Mendonça Filho (awarded the Palme for Best Director), follows a university researcher who turns against the military dictatorship in 1970s Brazil.

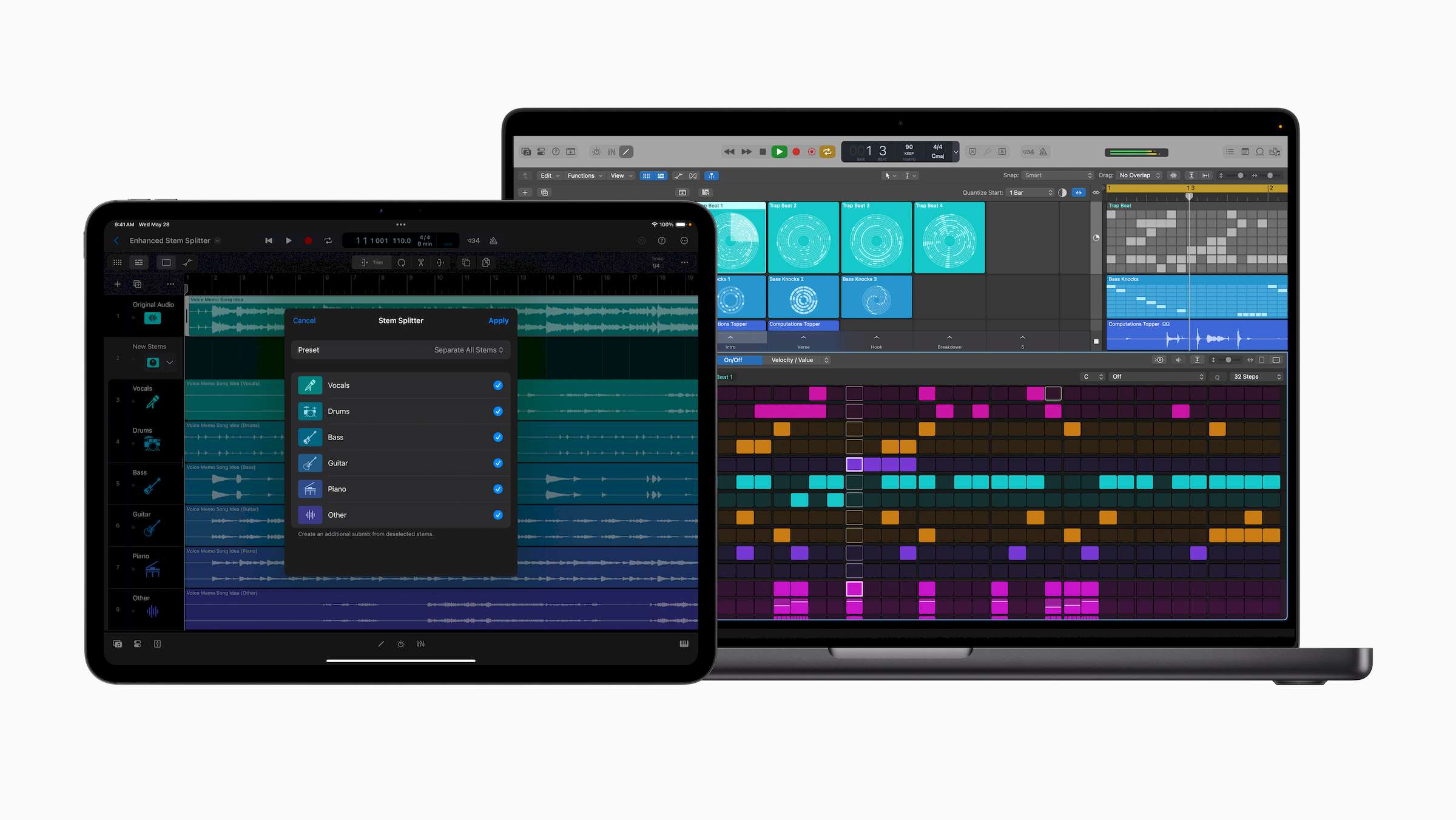

Top: It Was Just an Accident (Jafar Panahi, 2025). Bottom: Heads or Tails (Alessio Rigo de Righi and Matteo Zoppis, 2025).

Such rebellious fervor echoed from other sidebars as well. Heads or Tails, an Un Certain Regard standout, chronicles its own David-versus-Goliath fight. A freewheeling western set in post-unification Italy, Alessio Rigo de Righi and Matteo Zoppis’s latest probes the nexus between stories and myths—where the former becomes the latter, and how they endure. This is nothing exactly novel for the Italian duo, whose oeuvre has long been enchanted by the act of telling. Their first foray into fiction, The Tale of King Crab (2021), is a Russian doll of tales within tales: the story of a gangly drifter who flees his native hamlet in early twentieth-century Italy to seek El Dorado in Patagonia, it unfurls as a campfire yarn passed down through generations. Like that film, Heads or Tails is chiefly preoccupied with the way we all inevitably shape the stories we tell. Rigo de Righi and Zoppis foreground that interest from the start, kicking off with Buffalo Bill Cody (John C. Reilly, bedecked with a wide-brimmed hat and pointy white goatee) performing some kitschy reenactment of his Indian Wars antics for a crowd of Italian aristocrats. This part is true: In 1890, Cody had traveled to Rome to pay a visit to Robert Prevost’s predecessor Pope Leo XIII while on tour with his Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show when he brushed shoulders with some Italian cowboys and claimed his men were better skilled at taming horses. The bragging led to a bet, a rodeo contest was arranged, and the home team easily defeated the visitors. But in the filmmakers’ version of the events, the competition ends with a murder. Asked by his wealthy employer to take a dive as part of a gambling scheme, Italian ranch-hand Santino (Alessandro Borghi) refuses, beating the Americans only to flee the scene with his boss’s wife, Rosa (Nadia Tereszkiewicz), after she kills her husband. Thus begins a long and increasingly surreal horseback journey through the Italian countryside that sees the couple cross paths with bounty hunters, South American revolutionaries, and other odd wanderers that wouldn’t feel out of place in the pulpy dime-store novels that inspired the various chapters of Heads or Tails.

So far, so King Crab. But the historical framing makes Heads or Tails the filmmakers’ most overtly political project. In the late nineteenth century, Italy was still a very protean notion. A handful of duchies and kingdoms cobbled together in 1861, the country needed a unifying narrative to justify its existence almost as badly as it needed railroads to connect its towns and cities. That legends possess extraordinary powers is a lesson that’s not lost on Cody, who has made self-mythology his living, and Santino begins to see the benefits as well. Hunted by his former employers—convinced the murder was his doing, not Rosa’s—he is rescued by a small militia of Italian workers and happily plays along when they hail him as a kind of resistance hero. Heads or Tails may lack the dramatic propulsion and mysterious allure that made King Crab such a gripping watch, but it nonetheless echoes that film’s receptiveness to the surreal, combining magical realism with more observational, documentary-adjacent passages—none more mesmerizing than a short sequence featuring a group of farmers armed with mirrors they use to catch frogs, blinding them with sunlight. This part is true too, the filmmakers told me, citing the exorbitant number of sources and archives they consulted while working on the script.

You can sense their fastidious attention to the period’s textures everywhere in Heads or Tails; working with what was presumably a much larger budget than King Crab’sallows them to adorn their frames with more elaborate scenographies and lush period-appropriate garments. But this is no mere exhumation of a bygone world. If Heads or Tails feels refreshingly anachronistic, this isn’t a function of its defunct milieu, but of the old narrative practices and genre tropes the film employs to stage a dialogue between past and present. Conversant as it is with different approaches to the western—drawing from its spaghetti, revisionist, and acid variations— Heads or Tails also relies on popular verse to move the plot along. As characters sing, the journey swells into something closer to a racconto popolare—a folk tale. Together with Michelangelo Frammartino, Alice Rohrwacher, and Pietro Marcello, Rigo de Righi and Zoppis belong to a small, hallowed pantheon of directors building upon the country’s rich storytelling traditions as a means to locate the vestiges of the past beneath late capitalism’s façades. That their oeuvre feels so marginal to so much mainstream and arthouse Italian cinema is only a testament to its originality, and further evidence that the most singular filmmakers working in the country today are doing so on the periphery.

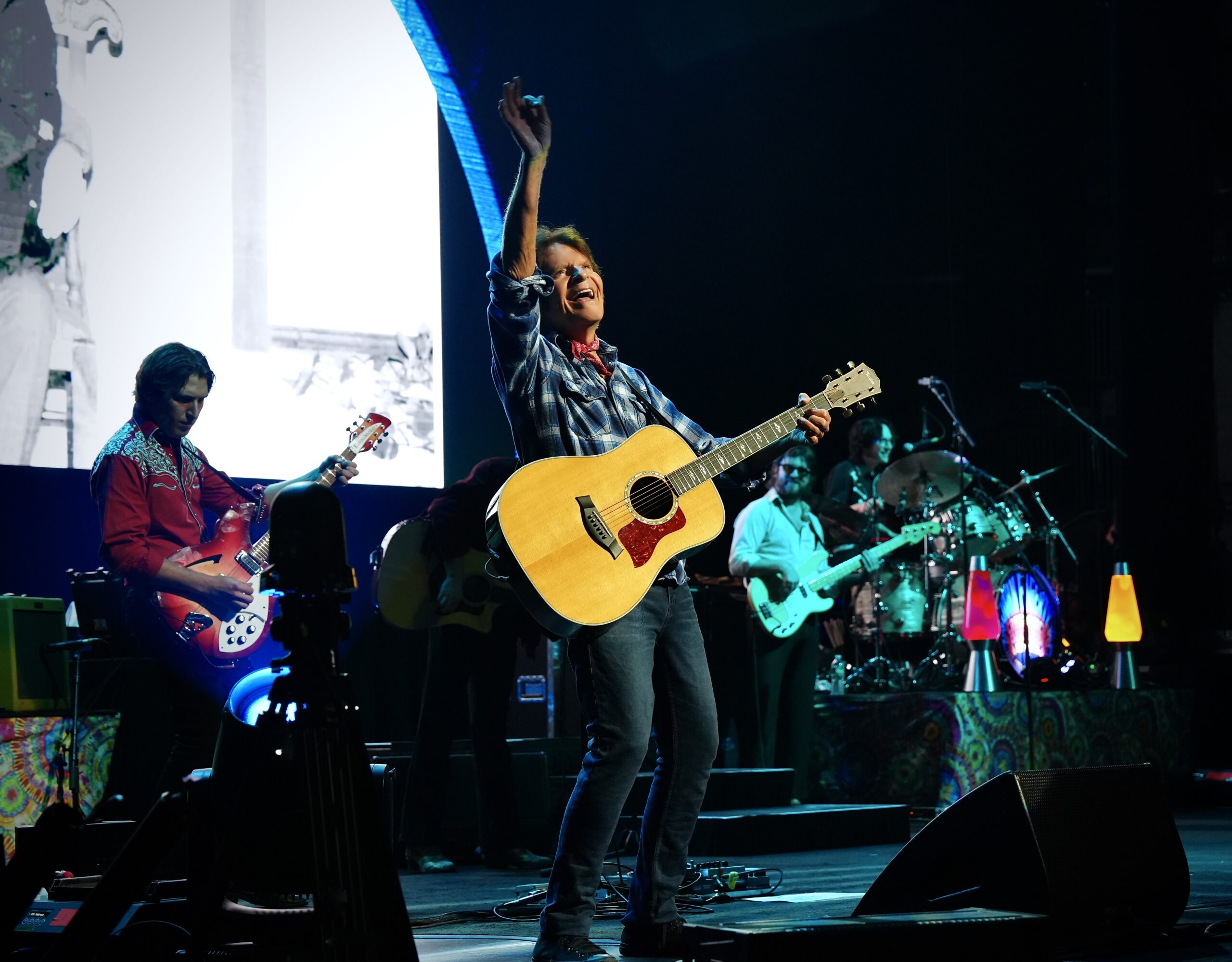

The Last One for the Road (Francesco Sossai, 2025).

Francesco Sossai is the latest addition to their ranks. His second feature, The Last One for the Road—another Un Certain Regard highlight and, in my book, one of the festival’s greatest discoveries—unfurls in the writer-director’s native Veneto, an ostensibly affluent industrial region in northeastern Italy immortalized here as something closer to a moribund, surreal no-man’s-land. At its center are two genial, 50-something tipplers, Doriano (Pierpaolo Capovilla) and Carlobianchi (Sergio Romano), best friends since childhood who’ve long since lost their jobs and wasted a small fortune on a Jaguar and a few too many drinks. Left with little to do other than reminisce about their salad days and avoid reckoning with the fact that the times are a-changin’, they undertake an endless and rambunctious drinking spree that puts them in the company of a young architecture student, Giulio (Filippo Scotti). Written by Sossai and Adriano Candiago, The Last One unspools as an alcohol-fueled road movie, with the two older wanderers acting as unlikely chaperones for Giulio’s sentimental education. The tonal whiplash and lilting tempo Sossai achieves are remarkable, avoiding the narrative fatigue endemic to the genre. Like his previous short, The Birthday Party (2023), The Last One is perched somewhere between facts and visions, as attuned to the ongoing devastation of the 2008 financial crisis across Veneto as it is to the improbable legends and anecdotes that unite its jaded residents. We hear of UFOs that supposedly materialized atop supermarkets, friends who escaped from justice and sought fortune in Argentina (not unlike King Crab’s hero), and a mythical three-wheeled Apecars race that was once Doriano and Carlobianchi’s most anticipated event of the year.

One way of looking at the film is as an alternative oral history of the region. A delirious and often moving voyage, The Last One is first and foremost a perceptive snapshot of a place on the verge of disappearing. As someone born and raised just a few miles away from Sossai’s hometown, I was especially impressed by the way his latest captures the area’s soundscapes; the omnipresent whirring of warehouses and factories as characters race past is just spot-on. Sossai is as preoccupied with the homogenizing effects of globalization (“This feels like the US,” the drunkards muse upon walking into a Wild West–themed bar) as he is with the way these villages are emptying out and turning into ghost towns (it is perhaps no wonder that the journey should end at a grave, the majestic Brion Tomb, a monument built in the late 1960s that stood in for the emperor’s headquarters in Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two, 2024). But this is no lugubrious watch. Sossai intersperses the trip with many humorous interludes, and the intoxicated, rambling chats never overstay their welcome. Elegiac as it may be, his film is so steeped in the specific patois, lore, and atmosphere of the place as to become a breathing archive. I can’t wait to see what he’ll do next.

Resurrection (Bi Gan, 2025).

When we spoke, the day after The Last One’s premiere, Sossai said Rigo de Righi and Zoppis were two of the very few contemporary Italian cineastes with whom he felt a certain affinity, not least for their interest in dredging up old genres and bringing them into conversation with the present. That’s one way of looking at Bi Gan’s Resurrection. Like Sossai’s, Bi Gan’s filmography feels somewhat incongruous with the rest of his country’s cinematic output. His first two features, Kaili Blues (2015) and Long Day’s Journey into Night (2018), are set in Guizhou, the director’s native province in Southwest China, and unfold as lucid visions—the rare films that do not just ape an oneiric aesthetic but seem to move like dreams, in a time- and space-defying feat of montage and continuous motion. And though his third isn’t quite as tethered to his turf, it speaks to those same ambitions.

Resurrection is a sprawling phantasmagoria spanning a hundred years of film history, a journey split into five chapters (plus a short epilogue), each of which boasts a distinct visual style and narrative technique. The story is at once immensely intricate and almost archetypal in its basic movements. In a near, dystopian future, humanity has discovered the secret to immortality is to stop dreaming altogether, leaving the few who’d rather enjoy shorter, more vivid lives to roam the Earth as “fantasmers,” rebels responsible for “bringing chaos to history” and “making time jump.” Hunting the fantasmers are special agents known as “Big Others”, tasked with killing the inveterate dreamers and keeping chronologies linear. Resurrection concerns one such fantasmer, a shapeshifting entity played in his various incarnations by Jackson Yee, who staggers into the first, silent film–adjacent chapter as a cross between Nosferatu and Quasimodo. Each of Resurrection’s five parts pivots on one of the five senses, and the opener centers on sight, beckoning us into a labyrinth of canted angles and shadowed sets that recall German Expressionism. It doesn’t take long for a Big Other (Shu Qi) to find him; moved by his final words (“Illusions may bring pain, but they’re incredibly real,” an intertitle reads. “I’d rather die than go back to that fake world”), she chooses to ease his death, shoving a reel of celluloid into his back and catapulting him into a string of films-within-the-film.

And so it is that the fantasmer shows up again in a WWII-set noir playing a killer armed with a fountain pen (hearing); a worker who, at a Buddhist temple, awakens a creature known as the Spirit of Bitterness (taste); a con man determined to teach a young girl how to guess the cards from a deck (smell); and finally, a young thug running after a girl with shades of Su Qui’s character in Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Millenium Mambo (2001) over a 40-plus-minute unbroken take that trails after them in a riverside shipyard on December 31, 1999 (touch). Bi Gan has employed such a long, unbroken shot in each of his three features; the entire second half of Long Day’s Journey into Night consists of a single hourlong shot that sends us down a hill via zip line and drone and into a maze of derelict buildings. Resurrection’s oner is less elaborate, but it once again demonstrates their entrancing ability to match choreography with spontaneity, at once meticulously studied and open to the unexpected. I will remember this one for a brief, scrupulously orchestrated passage in which the camera lingers on a street party where people move in fast motion while a black-and-white film screens at normal speed just behind them, but also for a seemingly unscripted moment toward the end in which Yee’s fantasmer steals a barge to sail away with his flame, but can’t quite keep the boat straight. In the end he manages, and in the sequence’s last miraculous seconds the couple exchanges a rabid kiss-cum-bite just as the sun appears on the horizon, a slice of light refracting over the water and through the early morning mist.

I can’t pretend Resurrection sustains that spellbinding power throughout. As an anthology, perhaps it’s only natural that some chapters should feel more transportive than others, and that the whole sprawl shouldn’t come across as cogently as it did in Kaili Blues and Long Day’s Journey into Night. But even when it wanders, Resurrection is clearly the work of someone animated by an unwavering belief in the medium’s capacity to convey a lot more than what we routinely expect from it. It’s a film of big ideas and wild tonal shifts, one that mixes fart jokes with quotes from the Buddha, and whose cast includes vampires, illusionists, gangsters out of a Jean-Pierre Melville crime caper, and spirits that pop out of rotten teeth. Most importantly, it stands out as one of very few titles this year that conjures a sense of sublime, the kind that single-handedly justified a trip to this overpriced stretch of the French Riviera. How can cinema be considered a dying art when films like this are being made?

Continue reading our coverage of Cannes 2025.

![Lost in the Desert [THE SHELTERING SKY]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/the_sheltering_sky.jpg)

![The Man Who Fell to Sleep [SWITCH]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/switch-barkin.jpg)

![Chains Of Ignorance [NIGHTJOHN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/nightjohn2.jpg)

![How Andor Season 2's Incredible Saw Gerrera Speech Came Together [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/how-andor-season-2s-incredible-saw-gerrera-speech-came-together-exclusive/l-intro-1748454449.jpg?#)

![‘The Young Mothers’ Home’ Review: The Dardennes In Polyphonic Mode Largely Ring False [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/30223935/The-Young-Mothers-Home-2025.jpg)

![‘The Six Billion Dollar Man’ Review: Julian Assange WikiLeaks Documentary Is A Bit Broad But Still Uncovers Urgent Truths [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/29154909/%E2%80%98The-Six-Billion-Dollar-Man-Review-Eugene-Jareckis-Julian-Assange-Doc-Is-a-Jam-Packed-Chronicle-of-Legal-Persecution.webp)

![Benicio Del Toro’s Year Of The Andersons Kicks Off With ‘The Phoenician Scheme’ [Interview]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/28174907/BenecioDelToroPhoenicianScheme.jpg)