Pietro Scalia on Editing for Bernardo Bertolucci, the Beauty of Keanu Reeves, and Collaborating with Ryuichi Sakamoto

Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha returned to theaters this month in a 4K restoration ahead of a 4K UHD on July 22 from Kino Lorber. The film follows Jesse, a 10-year-old American boy believed to be the reincarnation of the revered Buddhist monk Lama Dorje. His story is intertwined with that of Siddartha, charting his journey […] The post Pietro Scalia on Editing for Bernardo Bertolucci, the Beauty of Keanu Reeves, and Collaborating with Ryuichi Sakamoto first appeared on The Film Stage.

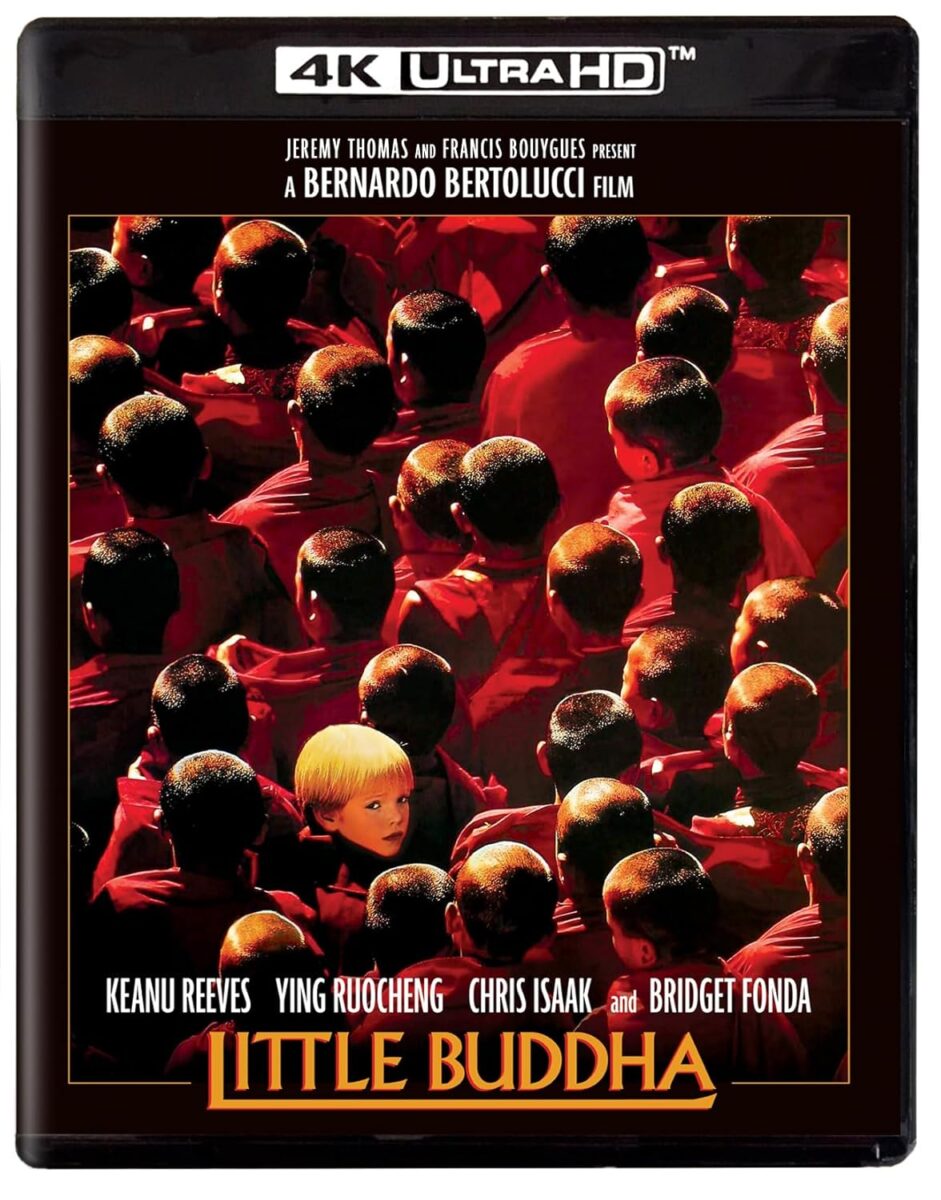

Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha returned to theaters this month in a 4K restoration ahead of a 4K UHD on July 22 from Kino Lorber. The film follows Jesse, a 10-year-old American boy believed to be the reincarnation of the revered Buddhist monk Lama Dorje. His story is intertwined with that of Siddartha, charting his journey to enlightenment. Bertolucci and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro filmed the two narratives using 35mm and 65mm, respectively.

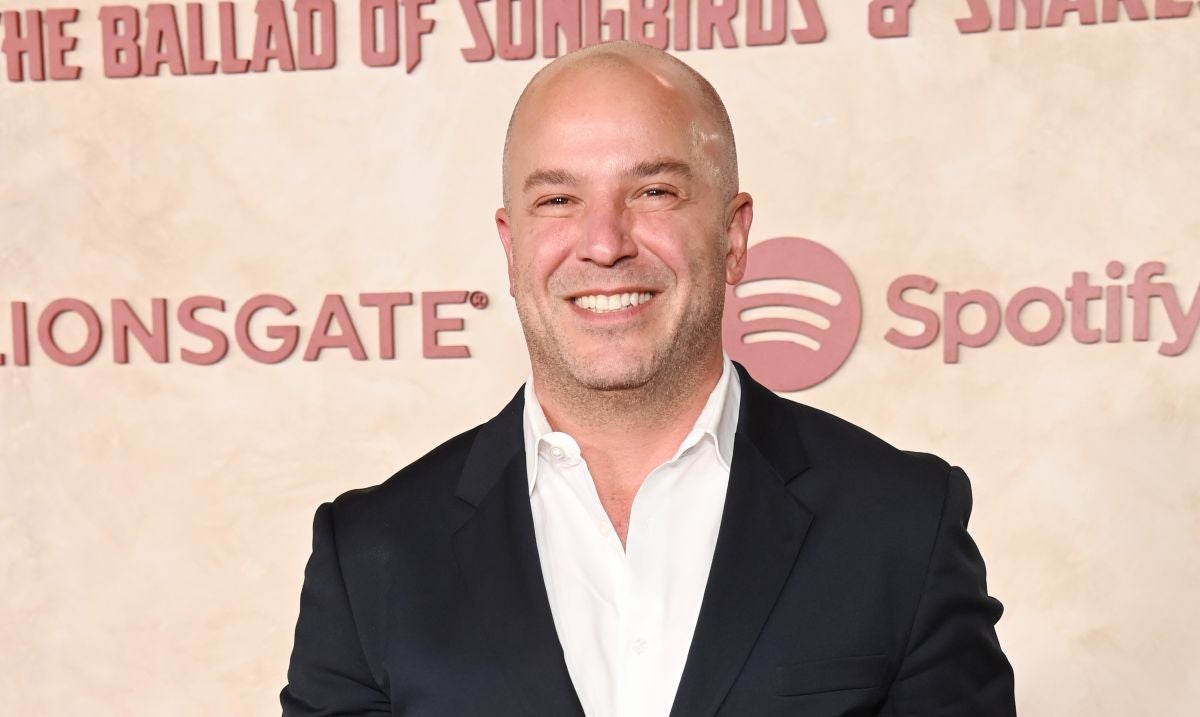

We spoke with Pietro Scalia, the film’s editor, who has earned two Academy Awards for his work on JFK and Black Hawk Down. Scalia has worked on a diverse range of films, from the intimate drama of Good Will Hunting to the epic scale of Gladiator. His extensive credits also include Hannibal, Memoirs of a Geisha, The Martian, and Ferrari, among others. Scalia’s approach to editing emphasizes rhythm, emotional impact, and narrative pacing.

Pietro Scalia: I remember that Bernardo, during that time, wanted to make Little Buddha accessible. So the idea is built into the DNA and the structure, to tell a story for somebody to understand Buddha through a child’s point of view. He’d never done it like that before. If you don’t know anything about Buddhism, that’s a way to get into the story.

The Film Stage: How did you first meet him?

I was in Rome in the summer of ‘92, and this was right after I had won the Oscar for JFK. I ended up going to Rome because an Italian producer heard that I would have loved to work in Italy. Nobody knew who I was; I was very young. I’m Italian, but I also grew up in Switzerland and then I moved here [L.A.]. I did not have an Italian base, but I did several interviews saying that my dream would be working in Italy. One producer called me saying, “Hey, I have this picture. Would you be available? My editor has another commitment. Can you finish it?” And I said, “Yes, sure.” It was three months in Rome. I went with my family and stayed there. That summer in Rome was a great experience because I got to meet a lot of filmmakers, journalists, and people in the film business. And one evening, at a party, I was introduced to Bertolucci. He was very sweet and told me how much he loved JFK and that it was incredible how young I was. Obviously I was blown away, as a massive lover of all his movies.

I met him again on a second occasion but I didn’t make much of it. I knew he was preparing Little Buddha but my impression was that he was going to continue working with Gabriella Cristiani. He had just finished The Sheltering Sky and The Last Emperor. I returned to the United States and I got a call from the producer, Jeremy Thomas; he said Bernardo has asked him to call me and would like to give me a call. “Oh, wow. Yeah, sure,” I said. “What is this about?” And so Bernardo called me. And we had this conversation, and he offered me Little Buddha. I was really shocked, surprised, and a few days later the Italian line producer––a great man, Mario Cotone––called me and said, “I’m Mario Cotone and I have to do the dirty work.” He goes, “How much do you want?” You know, the typical Roman way. I said, “How much would you give me? Fine. Just give me whatever you want.” He said, “Okay, you’re going to be leaving in three weeks. We’re already going to Nepal. We’re going to be shooting in Kathmandu.”

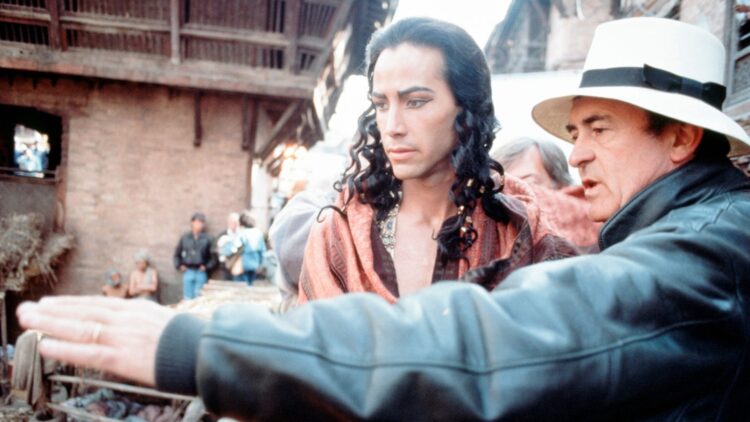

So three weeks later I went to Nepal, ending up in Kathmandu, and it was an amazing journey; it felt like going back in time. And when I arrived in Kathmandu… it’s a funny story. It was probably 7 in the evening and I entered the lobby and saw a lot of people that were all staying there, the whole crew––Italians and English people––and then I saw this man with gray hair and thought: “Maybe it’s Mario Cotone.” He looked at me, because I had just arrived and went, “Scalia?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “My God, if I knew how young you were, I would have offered you less money!” [Both laugh]

The great thing was that I finally got to work with an Italian crew, these masters. Obviously Storaro, who was going to film, but also other people like art directors, the production designer, camera operators, people who have worked with Bernardo for a very long time. They were really generous and very welcoming, so it was an amazing start.

So you filmed in Seattle later?

Yes, that was at the end. We shot over three months––in Kathmandu mostly, and nearby towns. I remember this historical square in Bhaktapur. At the end we moved to Seattle and shot for ten days, something like that.

Did you edit certain things on the spot?

At the beginning, a lot of it was not knowing how they work and getting to know them. I knew they were also using 65mm ARRI cameras. We had dailies that we would screen. We were still working on film. They would shoot, the lab would process it, we would get it back a few days later. So the first time we screened dailies, which nowadays nobody does anymore…

Except for PTA, apparently.

Oh, yeah? That’s great! That’s what we used to do: watch the dailies, everybody’s there. On the first day we had set up the projection in a ballroom at this hotel called the Yak & Yeti in Kathmandu. It was a nice, big room. We watched the dailies and I was sitting next to Bernardo. I had my notepad and I was expecting him to give me notes but he wasn’t giving me any. They were talking about the shoot. I said, “What do you want me to do?” And I remember him saying, “Well, it’s up to you to discover the design.” That was the way to learn how he worked. As a fan and as a lover of his movies, I could see both the lyricism of his long takes and the visual storytelling. I was just enamored by the material, getting to see this amazing footage. I started working on it, putting it together.

Pietro Scalia, photo by Giovanni Mecati

Who would watch the dailies?

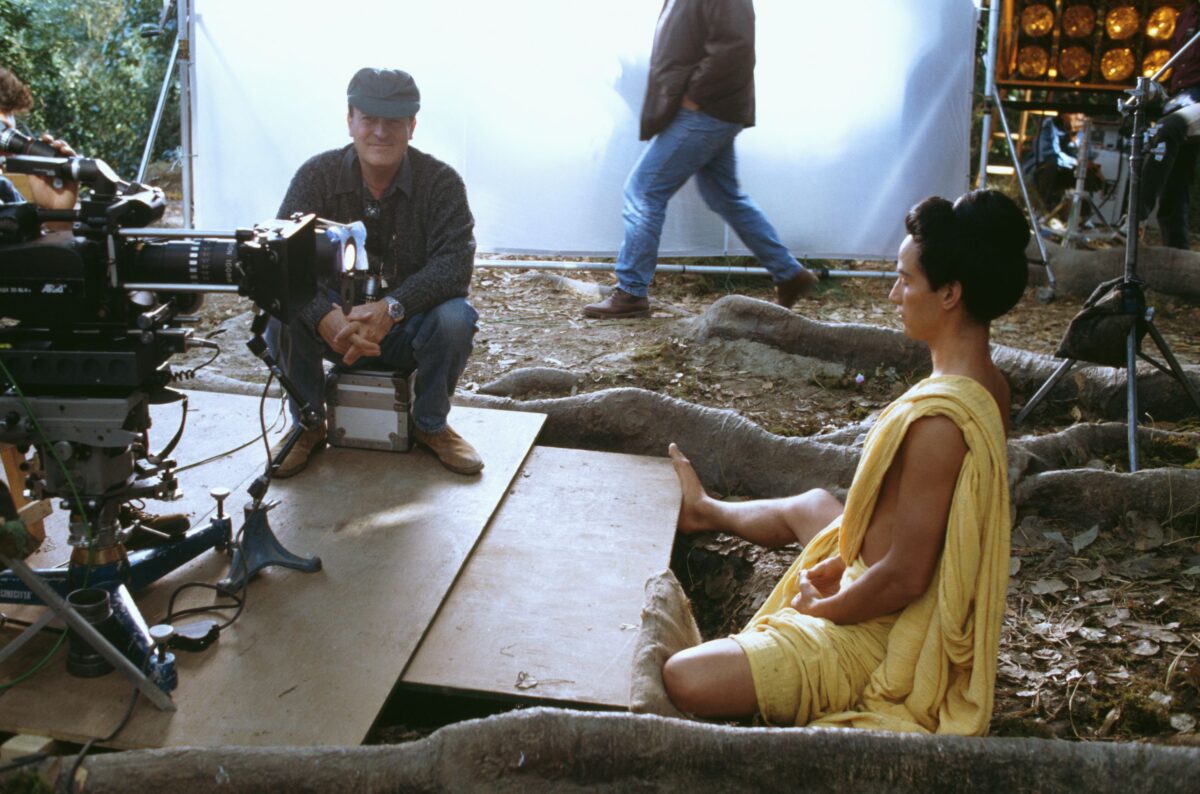

Bernardo, the producer, Storaro, the camera operator, the production designer James Acheson, the 1st AD––just a few people. I would say: maybe ten people. We also had a cutting room there; I had a flatbed Steenbeck flown in, and I assisted with the dailies. Bernardo wanted to come and look, and I would show him the scenes. I remember one of the first scenes was the one where the children move around the big tree and watch Siddhartha have visions while the camera circles around them. I put it together and cut one of these very, very long takes. Bernardo said, “Mi hai tagliato il piano sequenza? [You cut my long sequence?]” I said, “Oh, I’m so sorry!” And he replied, “No, no, no, I like it.”

But the thing is: I cut the shot moving forward, but I also cut a reverse shot with the actors coming closer to us. I didn’t have to do that, but there was something that matched the movement, the speed of the movement of both shots that it’s seamless. You don’t really notice; it’s not jarring. It’s a good cut. I didn’t have to, but I did, and he liked it.

So he would take suggestions? Many directors wouldn’t.

You cut a long take of somebody like Bernardo, who has planned it… but he could see that it was a beautiful cut. It made sense because the speed of the camera was identical, the motion of the actors towards the camera was the same. However, I have to say that I love to go to the set. One day I went on location and they were outside of the city in this field. They were shooting the scene of Buddha’s mom giving birth, and there were these big elephants, which I loved seeing. I wanted to experience how Bernardo and Vittorio shoot. I love Vittorio’s cinematography; I’m a big fan of all his work.

But what I didn’t know is––I mean, besides seeing the dailies with these beautiful long dolly shots––what surprised me is how Storaro was putting lights on dolly tracks. He had these lights which were connected to a very complicated lighting-dimming system––big lights, car headlights, two on either side with faders that could heighten or lower the density of the light––and several people gripping around with flags. So they were moving the camera, right? Then moving lights and moving crew with the flags. I thought, “This is choreographed!” Like a ballet movement. I could really see the symbiosis between the cinematography and Bernardo. That was quite special to witness.

Gabriella Cristiani said that the first time she saw the footage of The Last Emperor, she was in a daze at so much beauty. She thought everything was so beautiful that her real challenge was: “How can I make this uglier?” Did you have the same problem?

I have to say that it was very beautiful, and I remember we were in Rome, cutting at via Margutta, which is another great space. We were cutting, and at one point Bernardo wanted to show a first cut. He invited a few friends. Storaro came by, his producer, assistant directors, and a few friends. Maybe Gabriella was there as well; it could have been that she saw that first cut. It was about three hours long. And there was something really beautiful about it. Besides the image, the pace was completely different. You know, both Bernardo and I loved Satyajit Ray’s films. He actually suggested one I had never seen: The Music Room. It’s a story about this old noble man who has a palace, and all his riches are gone, but he still loves music and gives everything away in order to have another concert. Just beautiful, its lyricism. We listened to a lot of Indian music. His music supervisor provided him music from classically trained Indian musicians like Subramaniam, a great violinist.

So anyway: that cut was long and slow but it had a pace that we described, at one point, like a slow flowing river. It’s very powerful but moves very, very slow. And that was more the spirit of that kind of Indian pace. As we were cutting––this is at the time Miramax had picked it––they felt it was too long and kept shortening it. I think that sometimes I felt certain things were too short. And to my surprise, Bernardo didn’t mind it. He said, “I want to make it accessible to American audiences.” So we kept cutting and cutting, listening to Miramax and Harvey [Weinstein]. They were also favoring a little bit more the American or the Seattle part of the story, to anchor that more. And to me, I wish I had more of the other one, in terms of balance.

Keanu Reeves said all his favorite scenes were cut.

Yes, there was so much more.

Bertolucci didn’t want a director’s cut?

Years later, talking with Jeremy Thomas, I proposed to have one. I knew there was another cut there. Why not? Bernardo was still alive but there wasn’t any push to do it. I think it was just an acceptance that Bernardo was happy with it. One time James Acheson, the production designer, said, “Oh my God, you cut all that stuff!” And I know, but it’s not necessarily on me. I will not cut it because it’s bad but for the pressure to make it into a two-hour film. You lose something, you know? That kind of slow thing.

I agree with you. When I watch director’s cuts, I always feel they’re more organic. A good example is The Great Beauty. I think the extended cut has a much better pace.

Really? How much longer is that?

I think it’s 30 minutes longer.

A picture I didn’t do with Ridley Scott is Kingdom of Heaven. The studio made a shorter cut and it was terrible. Then Ridley made a director’s cut and that was far superior: the music worked, it was organic, the whole thing flowed better, it made more sense. Sometimes a movie has to breathe in a certain way, you know?

To me, the opposite is also true. Sometimes these films are too long and you should really cut them. I always think of Pawlikowski. You can accomplish so much in 90 minutes and you don’t need more than that. So it really depends on the story, right?

Yes, absolutely. Sometimes directors can be overindulgent. It’s a fine balance to find that kind of right rhythm.

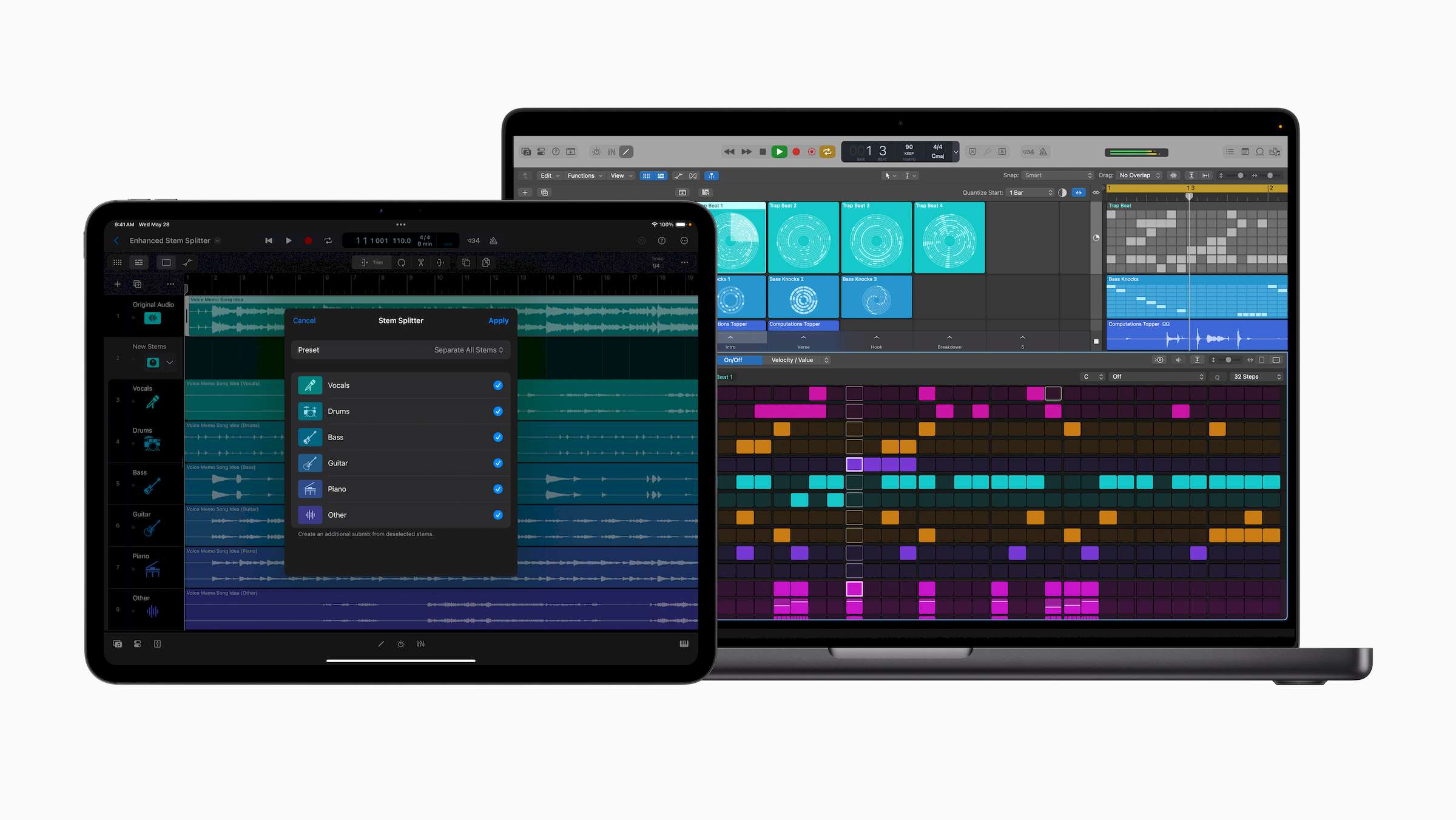

Because you mentioned music, how did you work with Sakamoto?

Sakamoto is great, and I’m also a big fan of his. He came on when we were editing in London––that’s where we had started our post-production. As soon as we started working, he started writing music. Both Bernardo and I also loved Górecki’s Third Symphony, and we took a couple of things from that. The thing is: I loved what Sakamoto was bringing to us, but there was an incident for the final music––you know, the giving away of the ashes––where we kept Górecki’s piece and Sakamoto really asked us to take it out. And Bernardo was like, “Okay, but you have to do as good as that.” And so there was a tall order for Sakamoto to match that. And he said, “If I get any closer, it’s going to be plagiarism.” Anyway, Sakamoto wrote beautiful music.

Did you discuss the political meaning of the film with Bertolucci? As we know, politics is always a big part of his films.

There was never any political discussion. He engaged with the Tibetan community and had a lot of good advisors on him. He had met the Dalai Lama, who gave his blessing. I think Bernardo’s point was that he wanted this to be innocent; he wanted that mantle of innocence.

He insisted a lot on that. He tried to cast another actor for the role of Siddhartha but then he was just very enchanted by Keanu Reeves’s innocence. He thought it was very rare for a young man––he was 28––to still have that.

Yeah. Bernardo loved My Own Private Idaho. Casting Keanu Reeves was such an unusual choice, but: a beautiful-looking guy.

This is interesting to me because I’m very familiar with Bertolucci’s filmography and political views. To me, the choice to open the film with the tale of the little goat and the priest says a lot. When Lama Norbu asks the kids: “What does this tale mean?” And the kids respond “that no living creature should ever be sacrificed,” it’s clearly a reflection of Buddhist teachings. But it also reflects Bertolucci’s stance on leftist movements. He was strongly against the use of violence or the idea that the single should be sacrificed for the greater good of the party, country, or any cause. So this idea that every human being is unique and important. He also grew up Catholic and the story of Siddhartha shares many similarities with the story of Saint Francis, if you think about it.

We never talked about politics, and specifically for that movie. I just remember the experience of working with him. When we edited, he would tell me stories about Pasolini, or his dad, or Moravia or other writers.

Attilio Bertolucci, his father, is one of my favorite poets––truly one of the best of the last century.

I know, I know. And I met his father––he was quite a charismatic man. He was very knowledgeable; he knew about films before Bernardo. Bernardo and I talked about Renoir and Godard but also Japanese movies––Mizoguchi and Ozu. That’s what I remember from the cutting room: Bernardo being always present, reading the newspapers in the morning, having his coffee, and just telling me the stories. It wasn’t about “cut here” or “cut there,” It was entering this world of total love of cinema and just being part of that. It was quite special.

Yeah, you know, I’ve never heard anyone say they had a bad experience with Bertolucci. With famous directors, you usually hear all kinds of unpleasant stories. But with him, it seems like everyone has nothing but love and admiration.

I would say he was one of the most generous masters I have ever worked with. He was very generous to me and also gave me creative freedom. I have to tell this story because it’s so typical of Bernardo. One time he looked at my hands and said, “I like your hands. When you cut, I feel your hands all over my body.” [Laughs] Just like that. That’s a Bernardo expression, right? “I feel your hands all over my body”––because that’s the film and it’s very physical, the act of touching it.

Let’s talk about the special effects. There’s a few things I really like. The lotus blooming, and also when they get to Seattle: they drive, talking about the dream of the Lama Dorje, and the house appears.

It was 1993. It was an early stage of digital effects.

I think that’s why I like it: you can feel the craft.

I remember when they were shooting the sequence of the bad demon, the alter ego who is trying to seduce Siddharta. Nicola Pecorini is a friend and the camera operator who shot that sequence––you know, those shots of the hill with the soldiers. That was a complicated sequence to put together. I just recently saw him and he said, “Similar things happened in Gladiator.” He meant the arrows––you know, the arrows flying. We flopped shots, we duplicated it, so you can make it look like a huge army is coming down. There are similarities between the way we used special effects in Little Buddha and Gladiator. With the Seattle part, Storaro had very specific ideas––besides the different format, 65mm instead of 35mm. Though the film was lush and warm with gold and red colors, Seattle was completely cold and bleak. It’s a little bit of an extreme, because Seattle is beautiful.

And then it warms up at the end, right? As a way to underline this internal struggle.

I have to say that, on digital, the color seems very, very harsh. You don’t see the subtleties of it.

Storaro has very strong opinions when it comes to color.

I know. When you see a print it’s different, though.

I wanted to ask you about the job of an editor. I think it’s very similar to that of a director, right? People think these are very creative jobs, and obviously they are. But they’re also very technical. And you’ve worked on such a wide range of films. I was wondering: is there a difference in how you approach editing an art house film versus a more commercial movie? In other words, when you’re editing Stealing Beauty and The Martian, do you have the same approach?

I do. Besides the complexities and how many people are involved in final decisions in terms of costs, the fundamental thing for me is really about being inspired by the material that’s been shot, by what was written, and by the performance. Fundamentally, I go for the character to put the viewer in that experience. First character and story, and then later on I figure out structure. For me it’s also a discovery of that character. What is truthful? What rings true to me? Which emotions––how do you build that? And at the same time retain the musicality of a cut? You make choices, but to me it’s always about: do I feel something? Is it real? If I feel it, then other people will feel it. How can I reproduce that? Is it close? Does it change? Do certain things alter? The character, the reaction, the timing of it––I still approach editing that way.

Because we talk about Stealing Beauty, how was working on that second film with Bertolucci?

It was great. It was a simple story, coming-of-age, a girl spending her time in Tuscany, and it was based on Bernardo’s friends. There wasn’t much conflict in it for a drama. Like you said, in any good story you need conflict––whatever happens to your character––to make it dramatic. And I asked Bernardo. He said, “Yes, I’m not interested in conflict. This is just a chamber piece. Four musicians playing, not a big orchestra. This is small and intimate.” It was also the first time he worked with a different DP: Darius Khondji, who I admired for his work on Seven. They were shooting pretty much in one location, not very far from Siena, in Chianti. And I had my cutting rooms literally two minutes away from the set of this vineyard, at Castello di Brolio. Now I was working digitally, on Avid, and from my window I could see the set.

Wow.

I mean, these are dream jobs, okay? [Both laugh] Working with Bernardo is working in paradise. I remember I had my young family there as well, the kids, and so my wife would come by and we would go down to the set. We just sat there, literally in Tuscany, outside, and it feels like a family making movies. It’s just a dream come true. But I did observe again how Bernardo works. You know, with the camera, with the light, with Darius. You could see the same idea: waiting for the perfect light. If you’ve been in that area, Siena, it’s gorgeous––the light, how it cuts. And I could see from the dailies––I mean, Liv Tyler turned 18 on set––that depending on what time of the day they would shoot, the light was reflecting her skin differently. Sometimes it would be very pale, almost porcelain; sometimes more rich and lush, showing this blossoming beauty. Bernardo used this light with Darius, and it was beautifully done. It was gorgeous.

Now, before even starting that picture, since I like music, I said: “I’m going to bring a lot of music with me. What would this character, this 18-year-old girl, listen to?” I brought female singers––Liz Phair, PJ Harvey––but also music from Massive Attack. Bernardo brought Nina Simone and other pieces that we used. I put the music together, Bernardo would listen to it. And those pieces became part of the soundtrack which gave this kind of youthful feeling. When we screened the film I met Giuseppe, his brother. I remember he liked the film, but for the music he said, “È un’americanata. [It’s a typical American-style extravaganza.]” But Bernardo’s spirit was open to those things; he was welcoming you. He said, “No, I like that.” He felt surrounded by you. He did not think it was an americanata.

I love that scene where she dances alone listening to Massive Attack. That’s really beautiful, and the Italian title of the film, I Dance Alone, comes from that moment.

Yeah. The other one is the Mazzy Star song in the field scene. That was the music that I was listening to, I brought, and ended up in the film.

I think the contrast between music and images works really well, and that’s how poetry is born: when you have a strong contrast among things. Also, let’s not forget that Bertolucci was a published poet by the age of 12.

Brilliant. Was he 26 when he did Before the Revolution?

He was younger––he was 22.

Was he 30 when he did Last Tango?

Yeah. And it doesn’t matter how many times you’ve watched these films. When you rewatch them, you learn something new.

It’s true––some films last while others don’t. Unfortunately, the business has changed a lot. Like you said: people rush through things and everything becomes kind of homogenized. These films all look the same. Maybe there’s a few filmmakers, a handful, who still care for the craft––Nolan, Tarantino, or Spielberg. But, in general, the individual artistic voice gets lost. You see a slumpy camera and they say: “That’s an art film.” You know what? Godard was doing that in 1960; it’s not new. But try to do a shot like Bernardo and Storaro do. It takes a lot of time, and a different kind of sensibility, and there is beauty in that.

The new restoration of Little Buddha is now in theaters and arrives on 4K UHD on July 22.

The post Pietro Scalia on Editing for Bernardo Bertolucci, the Beauty of Keanu Reeves, and Collaborating with Ryuichi Sakamoto first appeared on The Film Stage.

![‘Elden Ring Nightreign’ Receives New Trailers Ahead of Friday Launch [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/eldenringnightreign.jpg)

![Chains Of Ignorance [NIGHTJOHN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/nightjohn2.jpg)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)