Cannes 2025 | Cruise Control

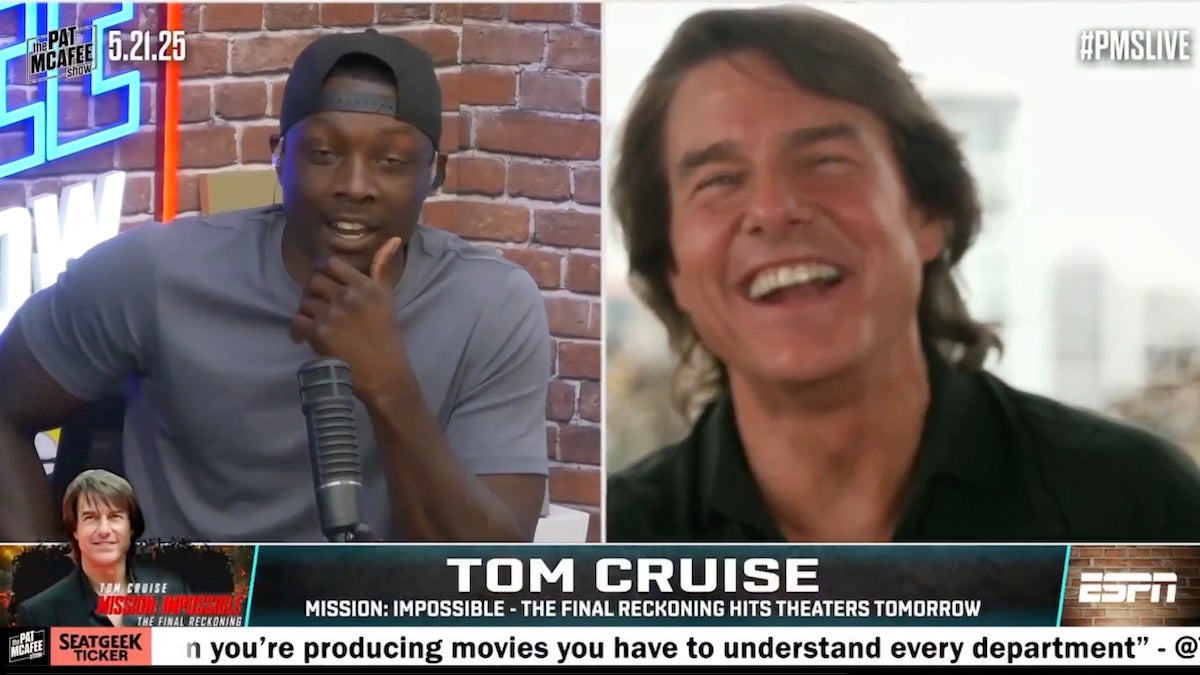

Illustration by Franz Lang.The precise recipe for an ideal Cannes Film Festival lineup is a mystery that inspires constant speculation and debate. The main ingredients are obvious: The films must be of high quality, of course, but a slate must also must balance prestige, artist relationships, business politics, and various diversity goals. Cannes being Cannes, star visits, rather than auteurist visions, are what galvanize public attention—especially American stars. The 2025 edition certainly checked those boxes, with two stars, Kristen Stewart and Scarlett Johansson, premiering their directorial debuts; elder statesman Robert De Niro received an honorary Palme, and nearly-as-elder Denzel Washington was surprised with one. But the biggest attention-grabber was that the self-appointed savior of moviegoing, Tom Cruise, deigned to bring his latest, possibly final, Mission: Impossible film to the Croisette. He wasn’t accompanied by the eight-jet flyover welcome that he received for the post-pandemic premiere of Top Gun: Maverick (2022)—along with his own honorary Palme—but showing up without gimmicks only proved just what a star the 62-year-old actor is. The film premiered in the 2,309-seat Grand Auditorium Lumière, a fitting venue to host the man who has branded himself as the cultural ambassador for watching movies in theaters.While many movies at Cannes don’t need a star, Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning (all titles 2025 unless otherwise noted), which premiered out of competition, would not exist without this one. The new franchise entry, a direct continuation of Dead Reckoning (2023), is the kind of globalized superfilm that is increasingly in jeopardy due to mammoth costs, distracted audiences, and diminishing standards of quality. From its early decades, American cinema has been exported abroad to maximize profits, but few films have had the overproduced yet recursive blankness of The Final Reckoning. An adventure geared toward remembering adventures past rather than sending us on new ones, it spends much of its 169-minute running time recalling earlier entries in the franchise, and indeed earlier moments in Cruise’s majestic career. These flashbacks, recaps, and reminiscences feel eerily like in memoriam clips, limited by IP necessity to his globetrotting, world-saving agent, Ethan Hunt. Throughout, everyone is repeatedly told that Hunt is the only man capable of the job, a tautology that ensures we can only imagine him doing it. Indeed, if Cruise ever stops making these movies, these movies will stop being made.Yet the franchise in its current form is a grandiose confusion. The Final Reckoning’s first hour, full of empty talk in abstract spaces, has all the discursive intangibility of art cinema. Disjointedly, there are two enemies: a villain so svelte as to leave no impression even while threatening global extinction, and a godlike rogue AI lamely pictured on screens as an early iTunes visualizer. Weak threats notwithstanding, the stakes are the end of the world. But the world we see, however exotic the settings, is a series of mundane action-movie backdrops against which increasingly convoluted pages of expository dialogue play out. Everyone in the film, and the film itself, is adamant about the high stakes of everything, but within the film’s self-enclosed world, the anxiety appears delusional. Above all, the worry seems to be that the franchise, and perhaps cinema itself, might be extinguished if Cruise fails. It is uncertain how many more movie stars of Cruise’s inexhaustible charisma and energy will follow in his footsteps, and how many more $300+ million films can be made, but The Final Reckoning’s strained portentousness felt above all like desperation, needing viewers to believe not just its premise, but also how impressive it all is, how essential. Quite the opposite: The film has polished the grinning gleam of Tom Cruise to a superfine, frictionless surface, a consumer object so ruthlessly manufactured that it appears from certain angles without luster at all. Highest 2 Lowest (Spike Lee, 2025).Perhaps these are the conditions for and the results of making big-budget movies with our few remaining stars, for Denzel Washington’s presence also produces an uncanny effect in Spike Lee’s Highest 2 Lowest, which likewise premiered out of competition. It would be unproductive to compare Lee’s film to Akira Kurosawa’s kidnapping epic on which it was based, except to say that Toshiro Mifune, the star of High and Low (1963), is only one part of a larger tapestry woven from fraught class conditions and cutting-edge policework. Conversely, Washington, a similarly iconic and intense actor, is Lee’s film in the same way Cruise is The Final Reckoning: The whole enterprise bends around him like light warps around a heavy body in space. An internally mysterious actor of great beauty, Washington, like Henry Fonda before him, exudes moral rectitude inextricable from a deep, possibly impenetrable privacy. S

Illustration by Franz Lang.

The precise recipe for an ideal Cannes Film Festival lineup is a mystery that inspires constant speculation and debate. The main ingredients are obvious: The films must be of high quality, of course, but a slate must also must balance prestige, artist relationships, business politics, and various diversity goals. Cannes being Cannes, star visits, rather than auteurist visions, are what galvanize public attention—especially American stars. The 2025 edition certainly checked those boxes, with two stars, Kristen Stewart and Scarlett Johansson, premiering their directorial debuts; elder statesman Robert De Niro received an honorary Palme, and nearly-as-elder Denzel Washington was surprised with one. But the biggest attention-grabber was that the self-appointed savior of moviegoing, Tom Cruise, deigned to bring his latest, possibly final, Mission: Impossible film to the Croisette. He wasn’t accompanied by the eight-jet flyover welcome that he received for the post-pandemic premiere of Top Gun: Maverick (2022)—along with his own honorary Palme—but showing up without gimmicks only proved just what a star the 62-year-old actor is. The film premiered in the 2,309-seat Grand Auditorium Lumière, a fitting venue to host the man who has branded himself as the cultural ambassador for watching movies in theaters.

While many movies at Cannes don’t need a star, Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning (all titles 2025 unless otherwise noted), which premiered out of competition, would not exist without this one. The new franchise entry, a direct continuation of Dead Reckoning (2023), is the kind of globalized superfilm that is increasingly in jeopardy due to mammoth costs, distracted audiences, and diminishing standards of quality. From its early decades, American cinema has been exported abroad to maximize profits, but few films have had the overproduced yet recursive blankness of The Final Reckoning. An adventure geared toward remembering adventures past rather than sending us on new ones, it spends much of its 169-minute running time recalling earlier entries in the franchise, and indeed earlier moments in Cruise’s majestic career. These flashbacks, recaps, and reminiscences feel eerily like in memoriam clips, limited by IP necessity to his globetrotting, world-saving agent, Ethan Hunt. Throughout, everyone is repeatedly told that Hunt is the only man capable of the job, a tautology that ensures we can only imagine him doing it. Indeed, if Cruise ever stops making these movies, these movies will stop being made.

Yet the franchise in its current form is a grandiose confusion. The Final Reckoning’s first hour, full of empty talk in abstract spaces, has all the discursive intangibility of art cinema. Disjointedly, there are two enemies: a villain so svelte as to leave no impression even while threatening global extinction, and a godlike rogue AI lamely pictured on screens as an early iTunes visualizer. Weak threats notwithstanding, the stakes are the end of the world. But the world we see, however exotic the settings, is a series of mundane action-movie backdrops against which increasingly convoluted pages of expository dialogue play out. Everyone in the film, and the film itself, is adamant about the high stakes of everything, but within the film’s self-enclosed world, the anxiety appears delusional. Above all, the worry seems to be that the franchise, and perhaps cinema itself, might be extinguished if Cruise fails. It is uncertain how many more movie stars of Cruise’s inexhaustible charisma and energy will follow in his footsteps, and how many more $300+ million films can be made, but The Final Reckoning’s strained portentousness felt above all like desperation, needing viewers to believe not just its premise, but also how impressive it all is, how essential. Quite the opposite: The film has polished the grinning gleam of Tom Cruise to a superfine, frictionless surface, a consumer object so ruthlessly manufactured that it appears from certain angles without luster at all.

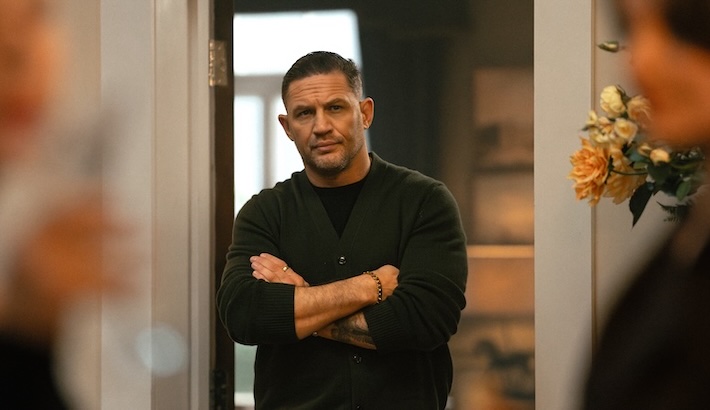

Highest 2 Lowest (Spike Lee, 2025).

Perhaps these are the conditions for and the results of making big-budget movies with our few remaining stars, for Denzel Washington’s presence also produces an uncanny effect in Spike Lee’s Highest 2 Lowest, which likewise premiered out of competition. It would be unproductive to compare Lee’s film to Akira Kurosawa’s kidnapping epic on which it was based, except to say that Toshiro Mifune, the star of High and Low (1963), is only one part of a larger tapestry woven from fraught class conditions and cutting-edge policework. Conversely, Washington, a similarly iconic and intense actor, is Lee’s film in the same way Cruise is The Final Reckoning: The whole enterprise bends around him like light warps around a heavy body in space. An internally mysterious actor of great beauty, Washington, like Henry Fonda before him, exudes moral rectitude inextricable from a deep, possibly impenetrable privacy. Something is shifting, though, in his recent work in Gladiator II (2024)and here: He appears more like an actor whose presence is somehow inside and outside the movie, as if he were a visitor to the set and to the fiction. In Highest 2 Lowest, he plays a legendary but waning music mogul whose son is kidnapped, yet despite his character’s drive to avenge the crime, Washington’s own engagement throughout the film seems fleeting. The movie is eager to keep up with this transitory, august presence. We watch Washington’s mind and acting work variously in sync with and independently from the drama of a scene: Any tension in the critical revelation of the kidnapping and the later realization that his chauffeur’s son was accidentally the victim feels diffused by the actor’s brusque, anti-climactic interpretation. In the face of such a capricious performance, whatever script there was seems to meekly retreat and its powerhouse director seems to coast.

Lee, one of America’s great artists, is both consistently erratic and astonishingly productive, able to pivot between unremarkable films and those which evince a cinematic brilliance all his own. In Highest 2 Lowest, his vibrant and disruptive side is mostly held in check. The scenario is so promising, with its milieu of Black wealth and power, clever locus in the music industry, and milieu of present-day New York. But these rich contexts for the kidnapping plot feel merely name-checked, and Washington’s off-kilter sincerity results in unexpectedly corny drama dosed by the director’s thriller clichés. There are indeed some of Lee’s joyfully overstuffed flourishes and ingenuity: a sudden shift from digital video to celluloid when Washington enters the subway to pay off the kidnapper, a Puerto Rican pride concert intercut with the money drop, and above all, a masterful confrontation between Washington’s mogul and an aspiring rapper played by A$AP Rocky. Staged in a recording studio, each on one side of the booth’s glass divider, it reinvents High and Low’s iconic ending on its own terms, revives the flagging story, and suggests the fully committed movie that could have been—something that grabs you by the throat. Instead, there is the sense of watching an actor have such an impact on set and on screen that the whole movie contorts itself to meet him on his own terms.

Eddington (Ari Aster, 2025).

Where Lee feels uncharacteristically restrained, a younger director exercising his privilege to do whatever he wants, for better or for worse, is Ari Aster, who is in Cannes for the first time. Eddington is his most ambitious film yet, a small-town portrait turned fresco of American society that chants “USA, USA” with a smirk. Presented in the main competition, it’s a cynical, darkly comedic tale of an already fractured community in New Mexico pushed over the edge by the pandemic in May 2020. Centering on a meek sheriff (Joaquin Phoenix, in a welcome comic mode) whose simmering feud with the mayor (Pedro Pascal) turns into a radicalized campaign to unseat him, the film watches a likeably bumbling, well-meaning, politically moderate American go mad as society implodes. Swirling in the increasingly manic atmosphere are many of the principal figures and topics of the American COVID era: online conspiracies, snake-oil messiah figures, pedophile paranoia, data farming, the Black Lives Matter movement, antifa terrorists, and social-justice warriors.

Commendable as such a post-2020 index of the components torquing American government and culture to a breaking point may be, Eddington is nevertheless beset by a bleak parodic perspective that can only identify extreme instigators of conflict and difference without recognizing any nuance. The result is an overwrought misanthropy common to the less pleasant side of the Coen brothers’ films, where an absurdist worldview can feel predetermined. The Coens at least are clear that they’re writing fables; Eddington revels in how relevant it wants to be, but can’t move beyond its own invented caricatures. The film is genuinely provocative in its aim to synthesize so much American distress, but its nihilistic comic spectacle feels little more than ghastly. Aster points out what is happening in America, but doesn’t have the curiosity or courage to wonder why.

Top: Case 137 (Dominik Moll, 2025). Bottom: Two Prosecutors (Sergei Loznitsa, 2025).

A rejoinder to Eddington's cartoon is Dominik Moll’s avowedly realist Case 137, a grounded and quite literally by-the-books policier—yet this proves a more incisive approach for exploring the world in which we live. Moll’s competition entry follows his excellent, low-key Zodiac-alike, The Night of the Twelfth (2022), both being bullshit-free exemplars of the kind of satisfying procedurals that were common in cinema for decades before finding a larger audience on television. The story of an internal affairs investigation into police abuse during the 2018 Yellow Vest protests in Paris, Case 137 follows the lead investigator (Léa Drucker) with a curiosity for and appreciation of where and how people work. With an ethical balance of characters worthy of Otto Preminger, Moll’s style reveals much more than Eddington’s morbid coarseness does, emphasizing the sanctity of law and objectivity in civil Western democracy—a sanctity that is shown to exist only in principle. In practice, Drucker’s investigator exists within the system she is tasked to police. Her ideals of culpability are gradually eroded by the consequences (and lack thereof) of her investigation, revealing that the face of fairness and justice worn by a government is only a mask. The system so thoroughly navigated in Case 137 as a means for policing the police, and thus keeping power in check, seems but a smokescreen of process with no intent to actually hold anyone accountable. By the end, the film calls into question whether a society based on such systems can be trusted at all.

Sergei Loznitsa would likely insist that it should not be. As the Ukrainian filmmaker has repeatedly made clear in his archival documentaries about the Soviet Union, recent history has seen supreme abuses of power, causing suffering and death among people whose stories are too often forgotten. Two Prosecutors, Loznitsa’s first fiction film since Donbass(2018), is set during the rarely filmed Stalinist terrors of the late 1930s but is nevertheless about a subject that is likely familiar to many: that authoritarian governments ignore due process, imprison and abuse the innocent along with the guilty, and obfuscate or erase entirely the records of their own crimes. The film follows a young, newly appointed prosecutor, Kornev (Aleksandr Kuznetsov), investigating a smuggled message from a political prisoner; after pressuring officials for access and hearing the prisoner’s testimony of his own torture and the confessions that were forced from other inmates, Kornev travels to St. Petersburg to present the report to the minister. A blunt work with, perhaps intentionally, no surprises, Loznitsa’s film reduces the process to simple essentials and lucid images: officials deflecting and delaying the investigator, creating an ambiance of threat, and finally resorting to imprisoning him as well. Its mise-en-scène consists of countless locked gates and receding stairwells—the prison’s thousands of inmates and their experiences of abuse are kept offscreen, in our imagination. In St. Petersburg, there is a mirrored reality, gleaming and bustling, but somehow full of similarly liminal spaces: waiting rooms, hallways with mysterious offices, stairways to unknown destinations. This unjust world is not exaggerated to grotesque effect, à la Brazil (1985) or even Eddington, but rather with dry, stark, and weighty directness. We watch Kornev’s foolhardy belief in the ethical righteousness of the system with an equally naïve faith that it could turn out differently for him than we expect. The endpoint of this journey is clear from the start, and watching what follows is not to wonder how it comes to pass, or even to be reminded that this has happened before. It is the eternal spectacle of state power: the persecution of the innocent under the guise of the just.

Death Does Not Exist (Félix Dufour-Lapperrière, 2025).

The secret agent, the kidnapper, the sheriff, the investigator: So many of these characters are tasked, or task themselves, with taking action to change the world. Félix Dufour-Laperrière’s Death Does Not Exist, a hand-drawn animated feature from Quebec that premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight, refreshingly looks not outward, but inward. Its subject feels even more contemporary than Eddington’s: Gen Z’s desire for social and political transformation, complicated by their own doubts and anxiety. A group of young adults gather in the woods, profess their solidarity with each other, and proceed to attack a countryside manor of the rich and powerful, guns ablaze. Hélène (Zeneb Blanchet) is one of the group, but during their final meeting, their faces lit by the smoldering shells of their mobile phones they’ve set ablaze out of precaution and defiance, her wide eyes radiate uncertainty about taking part in the extreme, murderous act. Failing to fire her weapon or support her friends during the ensuing bloodbath, she flees into the woods.

Rather than trace action, Death Does Not Exist takes the form of a fevered conversation between an imaginary survivor of the group and Hélène as she flees in confusion. Hélène’s swirling doubts contend with her friend’s recriminations and harsh moral scrutiny as the forest expands and hosts morphing visions of animals chasing one another and of their small town being radically reconfigured by nature—though whether for good or bad is unclear. The imagined debate and visions wrestle over the young woman’s wavering conviction and guilty betrayal, and her aching need to change a world full of misery and inequality. How this manifests, her actual beliefs, are mostly absent; the film keeps the conflict philosophical rather than dramatic. We cannot see her life, only what’s in her head.

Hélène’s journey acknowledges that processing emotions and questioning motives and morals are as critical to addressing injustice as action itself. Such honest turmoil with no easy answers stands diametrically opposed to the clear motivations and purity of heart represented by Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt, an ideologically blank hero appointed to miraculously save the entire planet. Cannes may need Cruise to bestow the holy light of the paparazzi on the festival, but we all need more movies brave enough to wrestle with what it takes to actually create change.

Continue reading our coverage of Cannes 2025.

![Fascinating Rhythms [M]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/m-fingerprint.jpg)

![Love and Politics [THE RUSSIA HOUSE & HAVANA]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/therussiahouse-big-300x239.jpg)

![‘Friendship’: Andrew DeYoung On Tim Robinson, Paul Rudd, & The Wildest, Cringiest Buddy Comedy Of The Year [The Discourse Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22133754/FRIENDSHIP-Poster.jpg)

![They Flew $19,000 Business Class—Here’s What I Think Denver Airport Execs Were Really Doing [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Denver_international_airport.jpg?#)

-1-52-screenshot.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)