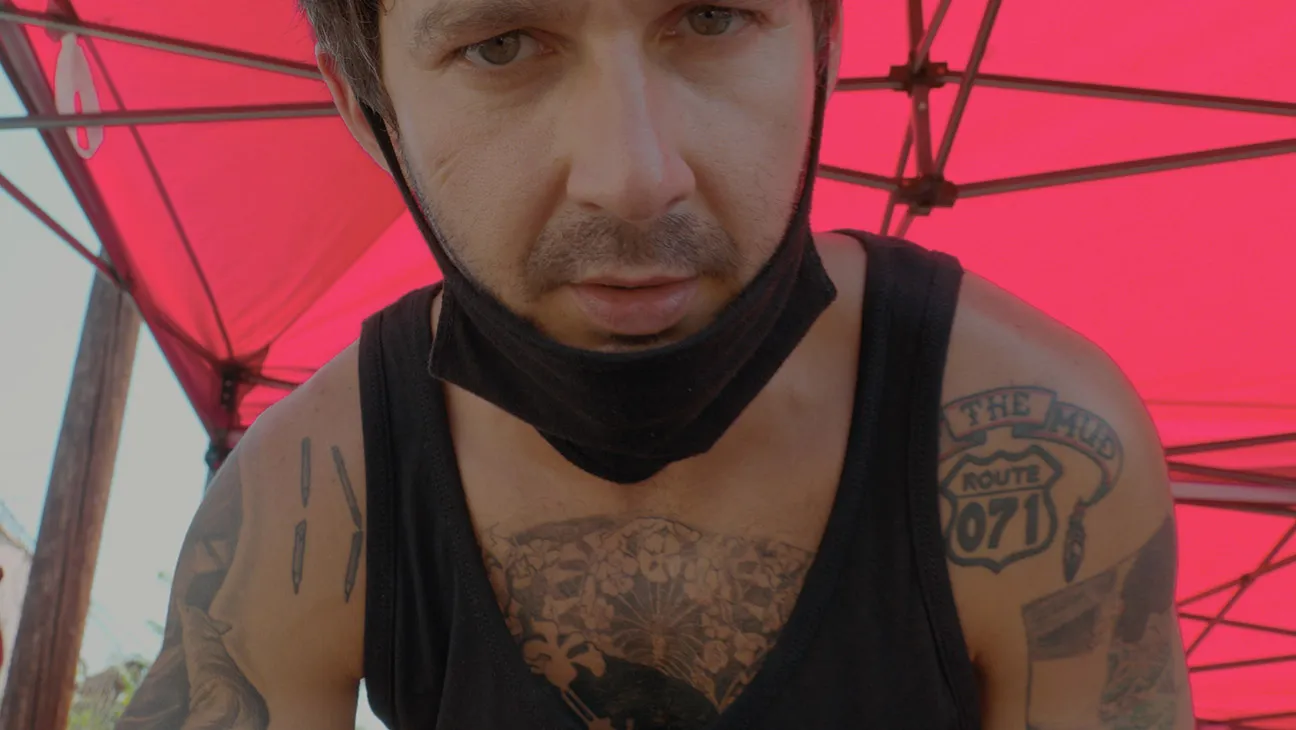

We Relate: Andrew DeYoung on “Friendship”

The filmmaker talks about his longstanding friendship with Tim Robinson, building comedy out of male emptiness, and more.

For comedian Tim Robinson, doubling down is almost always an unforced error, the kind of bad instinct that can escalate one fleeting social faux-pas into something far more catastrophic.

Across his absurd and hilarious sketch-comedy series “I Think You Should Leave,” the character type he excels at playing is that of an initially nice-enough guy—a little eccentric and prone to one peculiar grievance or another—whose frantically escalating efforts to save face after suffering a setback turn awkward moments into cringe-inducing nightmare loops.

At the center of these characters is a certain fragility of ego, a need to belong and be accepted in social situations despite their bizarre behavior, that Robinson exploits to perhaps even more discomfiting ends in Andrew DeYoung’s demented and hilarious comedy “Friendship,” now in theaters from A24.

In DeYoung’s feature debut, Robinson—in his first leading-man role—plays Craig Waterman, a socially awkward suburbanite whose corporate job involves developing “habit-forming” apps. At home, he’s an outsider, with wife Tami (Kate Mara) and son Steven (Jack Dylan Grazer) closer to each other than either is with him, and there’s no salve for the spiritual emptiness he seems to sense on a subconscious level—certainly not Craig’s catalog wardrobe (from an outfitter, inexplicably, named “Ocean View Dining”) or “the new Marvel” he optimistically talks about seeing (“I hear this one’s nuts,” he enthuses).

When he meets weatherman Austin Carmichael (Paul Rudd), who’s new to the neighborhood, Craig is completely smitten and more-than-slightly envious of Austin’s brand of cheerful, bro-y charisma. The pair gradually bond over ancient artifacts, punk music, and breaking into the mayor’s office via the sewer system—only for Craig to inadvertently ruin an evening with the fellas, leading Austin to break things off. What ensues is an amusingly off-kilter, creepingly strange series of events, as the uncomprehending Craig’s efforts to win back Austin instead trigger a hallucinatory trip, a missing-persons investigation, and sudden violence, wreaking havoc on both their lives in the process.

DeYoung has been friends with Robinson and Zach Kanin (with whom the comedian co-created both “I Think You Should Leave” and the sitcom “Detroiters”) since 2018, and that bond informed his vision of the script for “Friendship.” DeYoung wanted to lean into the anxiety and emptiness he senses in modern life, while also making a film about the absurdity of male-bonding rituals and socialization; Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master” was an unlikely but potent reference point.

“Friendship” had its world premiere at the Toronto Film Festival last fall, as part of the festival’s Midnight Madness program; it also screened at the Chicago Critics Film Festival and has been expanding in U.S. theaters since its initial May 9 release.

With “Friendship” now expanding nationwide, DeYoung jumped on the phone for a few minutes earlier in the week to discuss the “gut feelings” inside his new comedy, which scenes in the film were improvised, and the “pathetic” psychological tragedy of Craig Waterman.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Seeing your film at a sold-out advance screening during the Chicago Critics Film Festival has been one of my favorite movie-going experiences so far this year. What was it like for you to see “Friendship” with an audience for the first time?

Thank you for the kind words. The first time I saw it finished with a crowd was at TIFF. There were around 1,100 people, and I’d say it ruined my life in a way because I’m going to be chasing that feeling forever. It felt like a concert in there.

I didn’t realize the movie was that funny or could get that kind of reaction, so that’s been such an odd, cool thing for me to process. This movie plays quite well with a group of people, and it’s such a gift to hear people laugh in a room at these moments I wrote five years ago.

Tim Robinson has been called a master of cringe comedy; the adjectives I’ve heard applied to projects featuring him, like “Friendship, “I Think You Should Leave,” and “Detroiters,” are often variants of “awkward,” “anxious,” and “uncomfortable.” Is there a term you personally use to distill the comic sensibility of this film?

I don’t label it at all. I’ve no interest in that for myself, personally, and I don’t mind how people label these things, but I just follow what makes me laugh and feel something interesting. It’s a gut instinct; with comedy, we can only go with the gut. That’s where it comes from. Hopefully, it has laughs with depth, ideally. I love laughing and not exactly knowing why; that’s the goal for me.

The film’s aesthetic qualities add to that interplay between comedy and depth: all the careful compositions, the latent melancholy and dread of that wintry Yonkers setting. Look past the surface coziness of its suburban environment, and there’s an almost surreal menace and sadness lurking underneath.

I love hearing that. That’s so nice. It’s, again, just a gut feeling that I really gravitate toward. But “American Movie” is such a good example that I think about. So much of American comedy, I have no interest in, or I watch it and don’t really think about it much after. But there are certain films, like “American Movie” or this HBO documentary from the early 2000s called “Small-Town Ecstasy,” that are still deeply funny, but so many of the laughs come from this tragic behavior, from people trying their best and failing. There’s something deeply human about that that I am interested in. Rather than jokes, which I feel are common in American comedy, I want to see behavior, and I feel like the best behavior comes from putting people in tough positions.

Those tough positions, in “Friendship,” come about in part because of characters whose somewhat absurd behavior is motivated by this desire to perform, to project, to present in a society in a way that might not match who they actually are inside. I’d say both Craig Waterman and Austin Carmichael find their friendship caught in a kind of push-and-pull between external appearances and inner insecurities.

I wanted Tim Robinson’s character to be awakened by Austin. Parts of himself that he’s suppressed or repressed most of his life, he comes in contact with them, because with that feeling, when you meet someone new, whether it’s romantic, a friend, or something else, you feel kind of whole, more fully alive. That’s what I was chasing here.

And then, hopefully, at the end of the movie, we realize all that projection that he did with Austin has evaporated. He sees Austin for who he is, and they both actually begin a real friendship because they’re holding each other’s vulnerabilities for the first time rather than projecting onto each other.

You met Tim Robinson for the first time at Conner O’Malley and Aidy Bryant’s wedding, and you later wrote this role for him, having formed a friendship with him and Zach Kanin right before the first season of “I Think You Should Leave.” You’ve also worked closely with comedians Kate Berlant and John Early. I’m curious if forging friendships with very funny people informed the process of making “Friendship.”

I mean, these people are my friends because I’m a fan of theirs, but also because they’re just great people. And I feel so lucky to have gotten to know them over the years. Working with them, I know there will be a shorthand for how we can work. I don’t need to really teach anyone how to get to where we’re going. Everyone innately knows what works and what’s funny, and they’re just so brilliant.

Which matters when you’re orchestrating scenes like one standout between Conner O’Malley and Tim Robinson, two performers who take their comedy to such extreme, hysterical heights.

[laughs] That scene existed on the page, and it was half a page, but when we shot it, it was really the only improvised scene that we did, because Tim really doesn’t like to improvise too much. He can do it quite brilliantly, but he doesn’t really like to.

Tim and Conner are both geniuses, and they’ve known each other since [their time performing in the standup and improv comedy scene at Second City theaters in] Chicago and have worked together a bunch, and they also have such a shorthand; they can read each other’s minds in a certain way. They know the shape of the scene, they know what needs to happen, then you just let them go, and they come up with such brilliant stuff.

When you give a lot of trust to an actor, you’re going to get good stuff; even if you don’t know them, if you make them feel they’re allowed to fully play and explore, and you make them feel like everything is safe to try, you’re gonna get really good stuff. With these two, who are much funnier than me, you just let them go, and then you do slight adjustments.

Maybe we need a way to get here, something like that, but you just let them be brilliant and try things out. We did a few takes, and each take is 15 minutes long. They’re just going at each other, and it’s just unbelievable to watch.

I was going to ask you about your favorite scenes to film. It sounds like that was one of them.

That was certainly a highlight, just because Conner shows up on set, and he’s the nicest guy in the world, and then you watch him just become an animal and say some of the funniest things that you’ve ever heard—much funnier than I would ever come up with. It’s like watching magic.

To get into Craig Waterman as a character, this is a guy whose job involves developing apps that make people more addicted to their phones. Craig’s culture is consumerism, you could say, and many of his desires are manufactured. He can’t wait to see “the new Marvel.” Ocean View Dining is “the only brand of clothes that fit me just right.” Tell me about finding this market-obsessed character who’s so empty inside.

Yeah, that’s so good. I mean, he’s me in a lot of ways, just turned up and heightened. We are playing with the worst sides of ourselves when we fully accept culture, especially corporate culture, in the way that it’s spoon-fed to us.

I love it when people treat low-stakes things as high-stakes, and I love specifics. Tim loves specifics a lot. These things are all just coming from those specifics of the character that make me laugh.

For some of us, we have certain brands of clothes or certain foods, and we know they just work for us. The idea of doubling down on that is funny. And desire is so funny. Sometimes, when I see grown men with some sort of flashy shoe, I just like to imagine them at the store, looking at those, and being like, “Yeah, those are the ones.” [laughs]

People making choices at the top of their intelligence are always so funny to me, and I’m kind of rambling here, but some of these choices, and some of the details in this guy’s life, are all just extensions of all the specifics in our life that we don’t share with people. But we relate to them because we all have these little things.

And there’s such humiliation in having that bubble burst, realizing the brands that work for you are sometimes so generic or impersonal, or at least that they’re not expanding your sense of interior life. It’s not a rich emotional connection that one has with Ocean View Dining. But you’ve made a film about men of a certain age confronting that lack of interiority in themselves and each other. The drug-trip sequence gets at this — it could lead to this life-altering exploration of an inner self, but Craig realizes there’s nothing there to explore.

[laughs] And it’s not just men of a certain age, right? I think we’re all captured by the corrosiveness of capital, and we’re all so detached from our interiority, and that is leading to such tremendous suffering. And so, now, I’m playing it for laughs, and hopefully, there’s a cathartic relief in seeing someone so divorced from themselves because, in many ways, I think many of us are. I’m playing the despair, ideally, so that we laugh—and because we relate.

Collaborating with Sophie Corra, who edited “Friendship,” must have been a particularly important part of the process in that you were deliberately pacing this like a drama, not a comedy. She did similarly ambitious work with the tone of “The Scary of Sixty-First.”

I worked with Sophie on a previous project with John Early and Kate Berlant, and we hired her for this because she didn’t do comedy. She also clearly had saved “The Scary of Sixty-First,” you could tell—that’s an editor’s movie.

I have such a problem with modern comedy. It feels like it’s constantly selling out the emotional potential under so many scenes. And so I definitely wanted to work with an editor who had more of a footing in drama, rather than in comedy. Sophie’s an extremely funny person, and so smart, but, for this, my intention—as with everything I do, ideally—was to approach it with emotional gravity and respect.

I’m such a huge fan of so many arthouse filmmakers who know how to use the camera to add emotional weight and then let the actors deal with the comedy part of it. And to me, that mix of tones is something that I’m desperate for—and hopefully other people are too.

Looking at “Friendship” as a whole, can you speak to any particular beat, visual gag, or scene that you find particularly hilarious?

That’s such a good question. So many little moments make me laugh, and they don’t necessarily make the audience go crazy.

When I was at TIFF, what really made me laugh hard was when, right after he says, “She’s in the sewer,” and it cuts to the German Shepherd getting lifted. That was in the script, but it was supposed to be a dramatic moment where Craig’s, like, deeper and deeper in shit. But when we shot it and cut it together, that’s so fucking funny. I mean, he is deeper and deeper in shit, but look at the chaos, and the reality of it actually being played out.

It’s so pathetic, all of this. [laughs] Craig is just trying to find a friend, and now this dog is being shoved up this tunnel and struggling to get past it, just because he wanted to hang out?

Those little moments that I never really laughed at when we were editing, seeing them in context with a crowd was as if with fresh eyes. I’m like, “Oh, that’s really funny.” And there are a lot of those moments I had not necessarily intended to be funny, but—in context with a crowd—end up being big laughs.

At that moment, I felt an insane mind-meld between myself, Craig, and the dog, such profoundly shared discomfort.

[laughs] I haven’t talked about it—at all—until right now, but it is funny. That always gets a big laugh, because there’s something there. You’re right. There’s a perfect metaphor in there for the hell that’s happening in that moment.

“Friendship” is now playing in select theaters and expands nationwide May 23.

![Fascinating Rhythms [M]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/m-fingerprint.jpg)

![Love and Politics [THE RUSSIA HOUSE & HAVANA]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/therussiahouse-big-300x239.jpg)

![‘Friendship’: Andrew DeYoung On Tim Robinson, Paul Rudd, & The Wildest, Cringiest Buddy Comedy Of The Year [The Discourse Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22133754/FRIENDSHIP-Poster.jpg)

![They Flew $19,000 Business Class—Here’s What I Think Denver Airport Execs Were Really Doing [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Denver_international_airport.jpg?#)

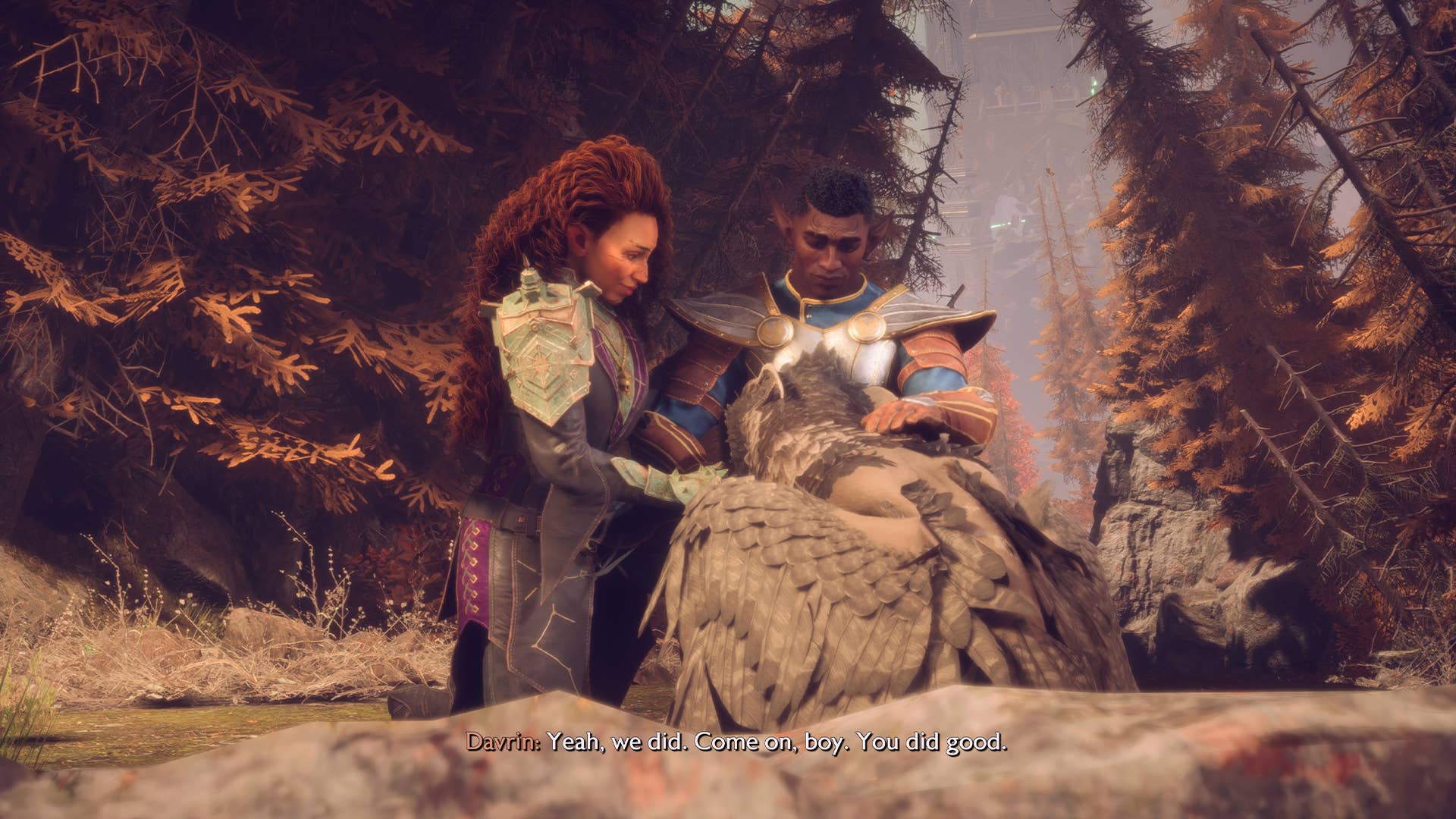

-1-52-screenshot.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)