Bird

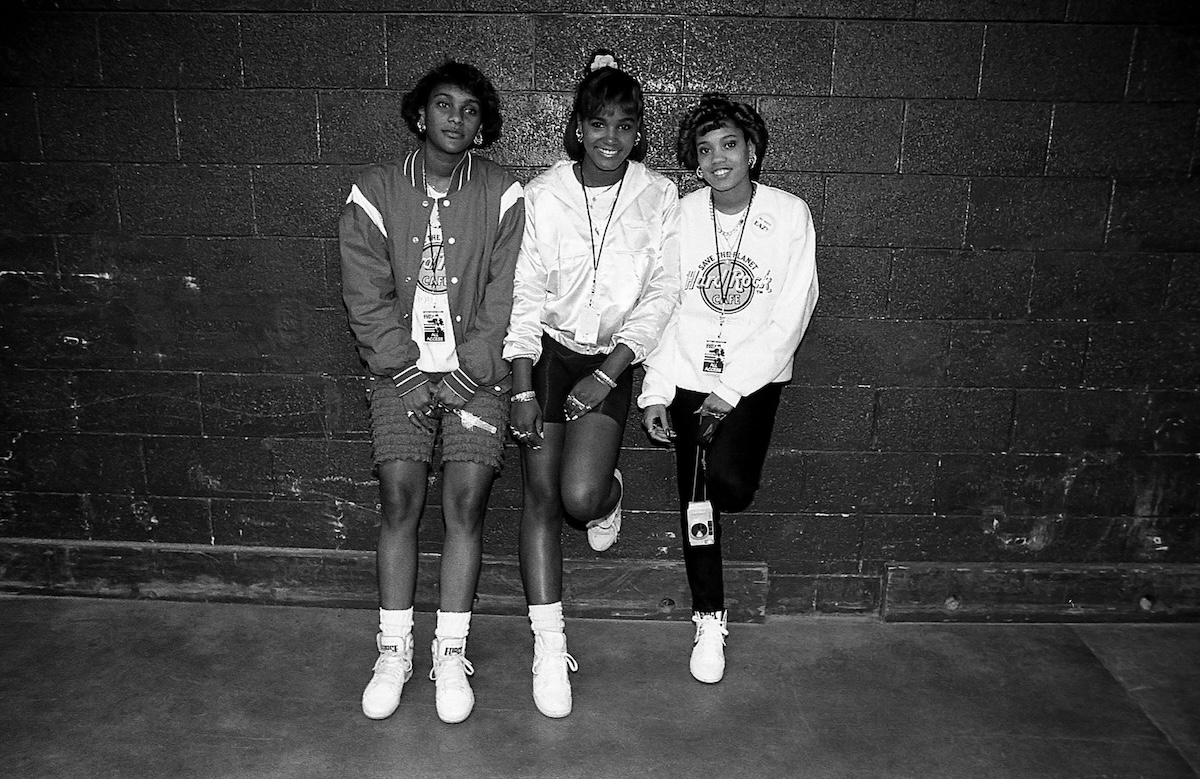

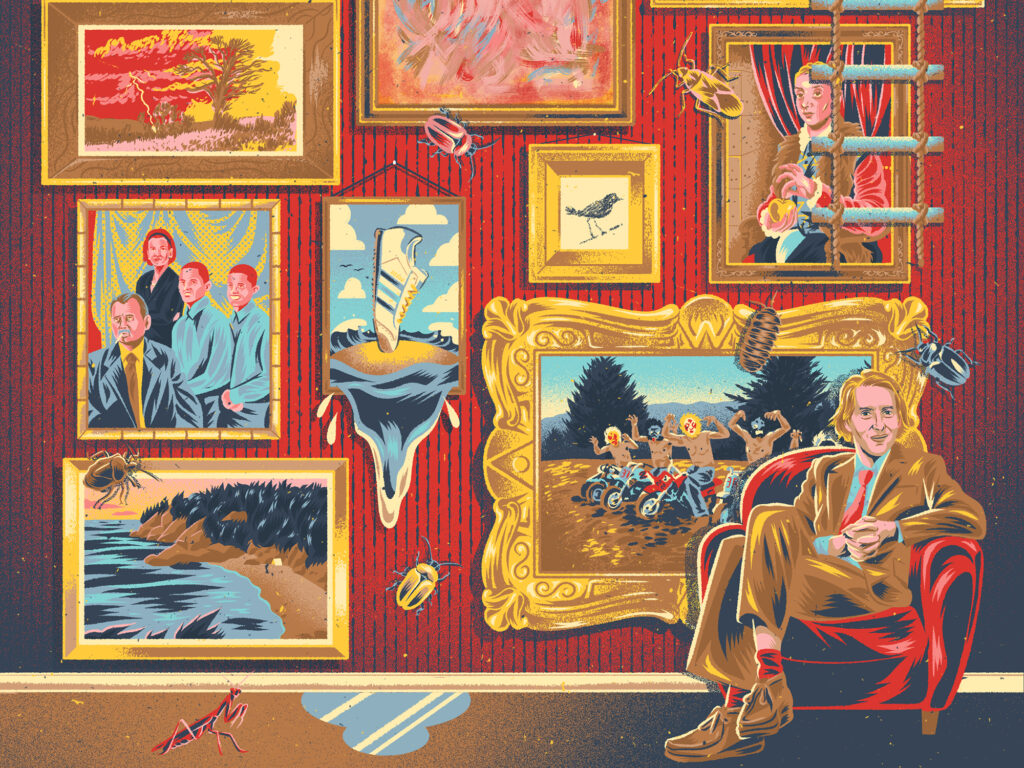

From the Chicago Reader (October 28, 1988). — J.R. Clint Eastwood’s ambitious and long-awaited biopic about the great Charlie Parker (Forest Whitaker), running 161 minutes, is the most serious, conscientious, and accomplished jazz biopic ever made, and almost certainly Eastwood’s best picture as well. The script (which accounts for much of the movie’s distinction) is by Joel Oliansky, and the costars include Diane Venora as Chan Parker, Michael Zelniker as Red Rodney, and Samuel E. Wright as Dizzy Gillespie. Alto player Lennie Niehaus is in charge of the music score, which has electronically isolated Parker’s solos from his original recordings and substituted contemporary sidemen (including Monty Alexander, Ray Brown, Walter Davis Jr., Jon Faddis, John Guerin, and others), mainly with acceptable results. The film is less sensitive than it might have been to Parker’s status as an avant-garde innovator and his brushes with racism, and one is only occasionally allowed to listen to his electrifying solos in their entirety, without interruptions or interference (as one was able to do more often with the music in Round Midnight), but the film’s grasp of the jazz world and Parker’s life is exemplary inmost other respects. The extreme darkness of the film, visually as well as conceptually, leaves a very haunting aftertaste. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 28, 1988). — J.R.

Clint Eastwood’s ambitious and long-awaited biopic about the great Charlie Parker (Forest Whitaker), running 161 minutes, is the most serious, conscientious, and accomplished jazz biopic ever made, and almost certainly Eastwood’s best picture as well. The script (which accounts for much of the movie’s distinction) is by Joel Oliansky, and the costars include Diane Venora as Chan Parker, Michael Zelniker as Red Rodney, and Samuel E. Wright as Dizzy Gillespie. Alto player Lennie Niehaus is in charge of the music score, which has electronically isolated Parker’s solos from his original recordings and substituted contemporary sidemen (including Monty Alexander, Ray Brown, Walter Davis Jr., Jon Faddis, John Guerin, and others), mainly with acceptable results. The film is less sensitive than it might have been to Parker’s status as an avant-garde innovator and his brushes with racism, and one is only occasionally allowed to listen to his electrifying solos in their entirety, without interruptions or interference (as one was able to do more often with the music in Round Midnight), but the film’s grasp of the jazz world and Parker’s life is exemplary inmost other respects. The extreme darkness of the film, visually as well as conceptually, leaves a very haunting aftertaste. Read more

![Wriggling Free of Perfection [THE EEL]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/theeel.jpg)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)