Cannes Review: A Poet is a Darkly Humorous Tale of Failed Creative Pursuits

Far removed from the mournful yearnings of A Quiet Passion––much less the quotidian, calming rhythms of Paterson––Simón Mesa Soto’s Medellín-set second feature finds unexpected poetry in the jagged, pained misery of dashed dreams and misinterpreted, career-ending good intentions. A Poet’s Oscar Restrepo (Ubeimar Rios), though 2,000 miles south of the down-on-their-luck, desperate characters often captured […] The post Cannes Review: A Poet is a Darkly Humorous Tale of Failed Creative Pursuits first appeared on The Film Stage.

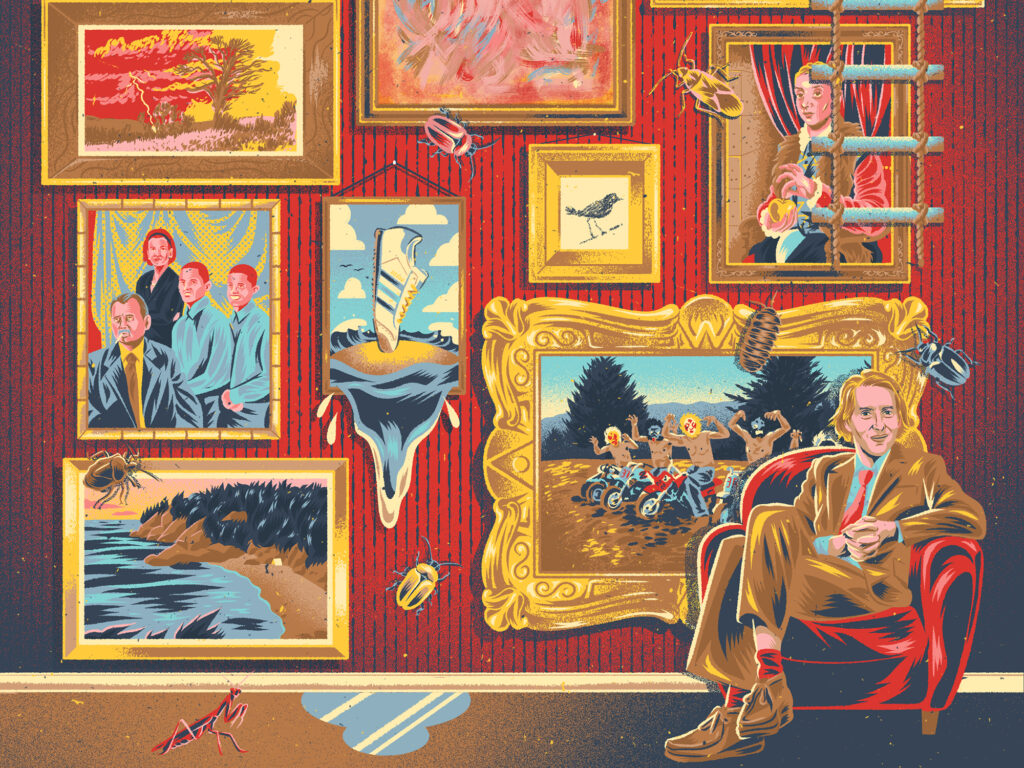

Far removed from the mournful yearnings of A Quiet Passion––much less the quotidian, calming rhythms of Paterson––Simón Mesa Soto’s Medellín-set second feature finds unexpected poetry in the jagged, pained misery of dashed dreams and misinterpreted, career-ending good intentions. A Poet’s Oscar Restrepo (Ubeimar Rios), though 2,000 miles south of the down-on-their-luck, desperate characters often captured by Sean Price Williams’ camera, would find some recognition in the shared Sisyphean struggle of striking out at every opportunity life offers up. This Un Certain Regard jury prize winner is a darkly humorous, cautionary character study in letting one’s long-lost creative dreams drive every decision––one in which Soto, more often than not, finds empathy as his protagonist circles the drain.

Still clinging to the dreams of being a celebrated poet––or at least one that will pay the bills––Restrepo has had an existence of seemingly self-inflicted trials and tribulations, going through a perpetual mid-life crisis some decades after published work was praised early in his career. He lives with his mother (Margarita Soto), has a rocky relationship with his teenage daughter Daniela (Allison Correa), harbors no bank account (much less pocket change), and spends what he can scrounge together to satisfy his alcoholism. Bloviating amongst his peers when he gets the chance to discuss his passion to a willing audience at the local poetry club, there’s the sense that Restrepo’s contemporaries just barely put up with his antics after years of infliction. After being more or less forced by his sister to teach a philosophy class at a local school to get his life in order, a beacon of purpose emerges.

Yurlady (Rebeca Andrade), one of his students, shows a way with both words and art, leading Restrepo to take her under his wing. Does he actually believe in her. Does he want to leech off her talent and gain inspiration through osmosis? Does he selfishly hope to be the savior for her to escape her lower-class life? Or perhaps this new relationship is simply a cipher to satisfy the pain of not having a connection with his own daughter? Soto, refreshingly, provides no precise answers, never painting in such clear-cut colors and always keeping one on their toes about Restrepo’s potentially amoral motives. Accusations of inappropriate conduct start surfacing after one particularly disastrous night, yet Restrepo believes he did everything with the best intentions; so ensues a complicated battle of wills between Restrepo, Yurlady, her family, his poetry club, and the administration of the school at which he teaches.

In what miraculously is his first acting credit, Rios gives a phenomenal performance, wearing decades of regret on his weathered, bespectacled face. With a nebbish demeanor when he doesn’t have the false confidence instilled by alcohol flowing through his blood, it’s clear he lacks the public-speaking skills or sense of professionalism of his peers, despite living a life dedicated to the art of poetry. There’s a defeated pain in Rios’ eyes that renders his character little more than, in the words of Billy Corgan, a rat in a cage. Using lively 16mm shot by Juan Sarmiento G., the camera is continuously fixated on Restrepo, trying just as much as the viewer to unpack the enigmas of his forlorn existence.

Repudiating what could have been a bleak, suffocating character study, Soto mines the humor of most situations, with quick cuts from editor Ricardo Saraiva punctuating Restrepo’s unceasing desperation, from sleeping on the street after drunk rants about legendary poets to crying in the car to rock ballads as we see his inner turmoil. He’s the kind of conniving character who vows he’ll help his daughter go to college and pay for her tuition in one scene, while in the next asking for five or ten bucks that he promises to pay back.

This kind of unscrupulous character study may test the patience of anyone wondering the point of watching this sad sack fall deeper into his self-made hole, and certain stretches suggest slightly extended repetitions of what came before. Yet as the Coens put Larry Gopnik through the wringer nearly two decades ago, here’s another updated telling of the Book of Job that finds an absurdly comic side to such afflictions. Ultimately finding welcome reconciliation after a drolly hilarious punchline to his dedication to Yurlady’s talent, Oscar Restrepo may be hapless, but he isn’t completely hopeless.

A Poet premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

The post Cannes Review: A Poet is a Darkly Humorous Tale of Failed Creative Pursuits first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Stephen King’s ‘Never Flinch’ Is a Messy Exploration of Feminism and Addiction [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Screenshot-2025-05-27-085722.png)

![The Studly American [APARTMENT ZERO]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/apartment_zero-poster.jpg)

![Money Changes Everything [GREED on video]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/greed-3leads.jpg)

![The Sun Also Sets [The Films of Nagisa Oshima]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/boy-flaginside.png)

.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)