Cannes Review: In Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind, Crime is a Losing Game

For the second time in three years, Cannes’ competition ends with a film in which Josh O’Connor plays a scruffy, late-20th-century man with some knack for pinching masterpieces. Following (spiritually or otherwise) Alice Rohrwacher’s La Chimera is Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind, an experiment in form so thorough and self-assured that even Robert Bresson might have […] The post Cannes Review: In Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind, Crime is a Losing Game first appeared on The Film Stage.

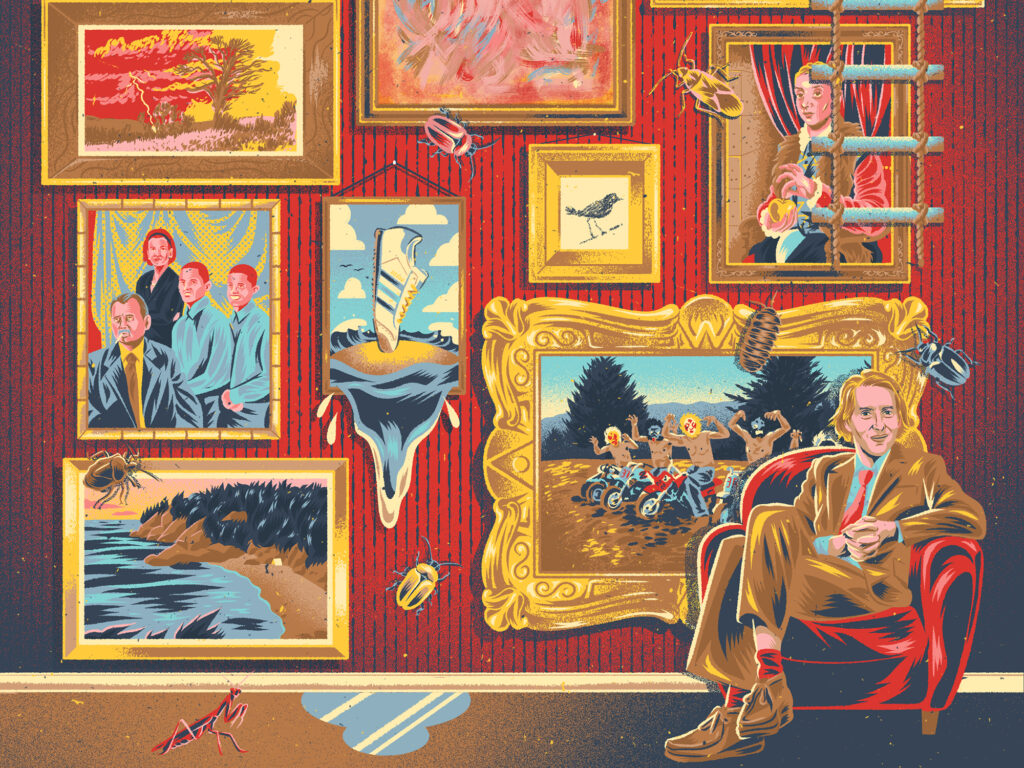

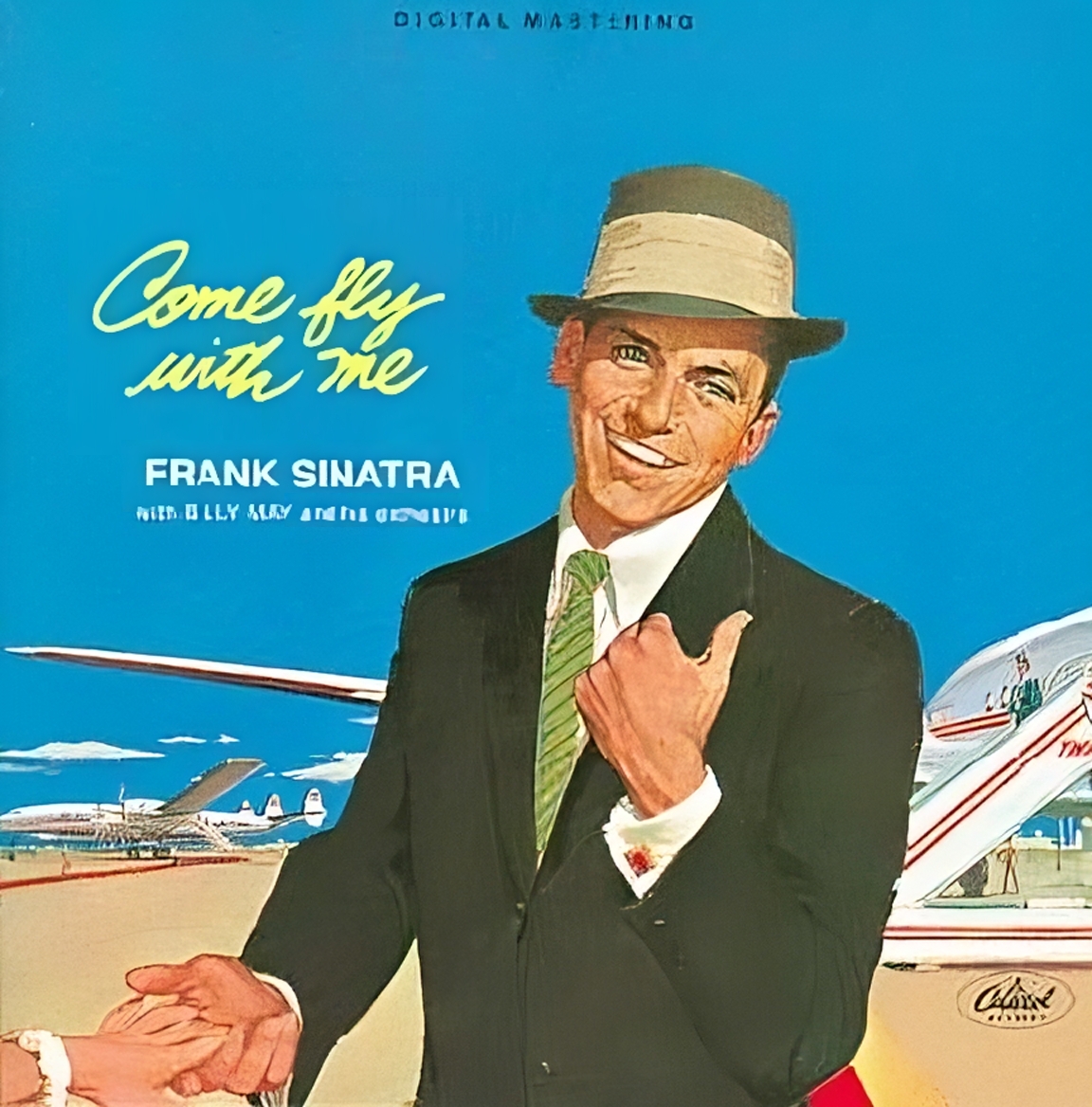

For the second time in three years, Cannes’ competition ends with a film in which Josh O’Connor plays a scruffy, late-20th-century man with some knack for pinching masterpieces. Following (spiritually or otherwise) Alice Rohrwacher’s La Chimera is Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind, an experiment in form so thorough and self-assured that even Robert Bresson might have appreciated it. Nobody expected the versatile director’s first heist movie to resemble Ocean’s 11, but The Mastermind is still remarkably low on flash. There is a jazzy score by Rob Mazurek and some even-jazzier opening credits, but this is very much a Reichardt joint: from its gorgeous, sylvan landscapes and autumnal color palette to the patient, observational tone, it suggests what robbing art in the early part of the 1970s might have truly felt like.

Whatever the case, The Mastermind will be billed as a new addition to the heist genre, as it has every right to be. Most key tropes are present: the singularly focused leader, the formation of a team (hello, bearded David Krumholz), the hatching of a plan, the execution, the nervy moments in and around the getaway car. I will be long dead before the world tires of these things, yet Reichardt isn’t out to satisfy with dopamine hits. Like Bresson’s L’Argent, The Mastermind bears little dialogue, which will come as something of a disappointment to anyone who saw Alana Haim’s name on the cast list, recalled her effervescence in Licorice Pizza, and began counting down the days until another turn. She’s one of many beloved actors left without a great deal to work with here, aside from O’Connor. Gabby Hoffman, John Magaro, and Matthew Mayer are given memorable moments, but their characters are left dangling amongst the threads.

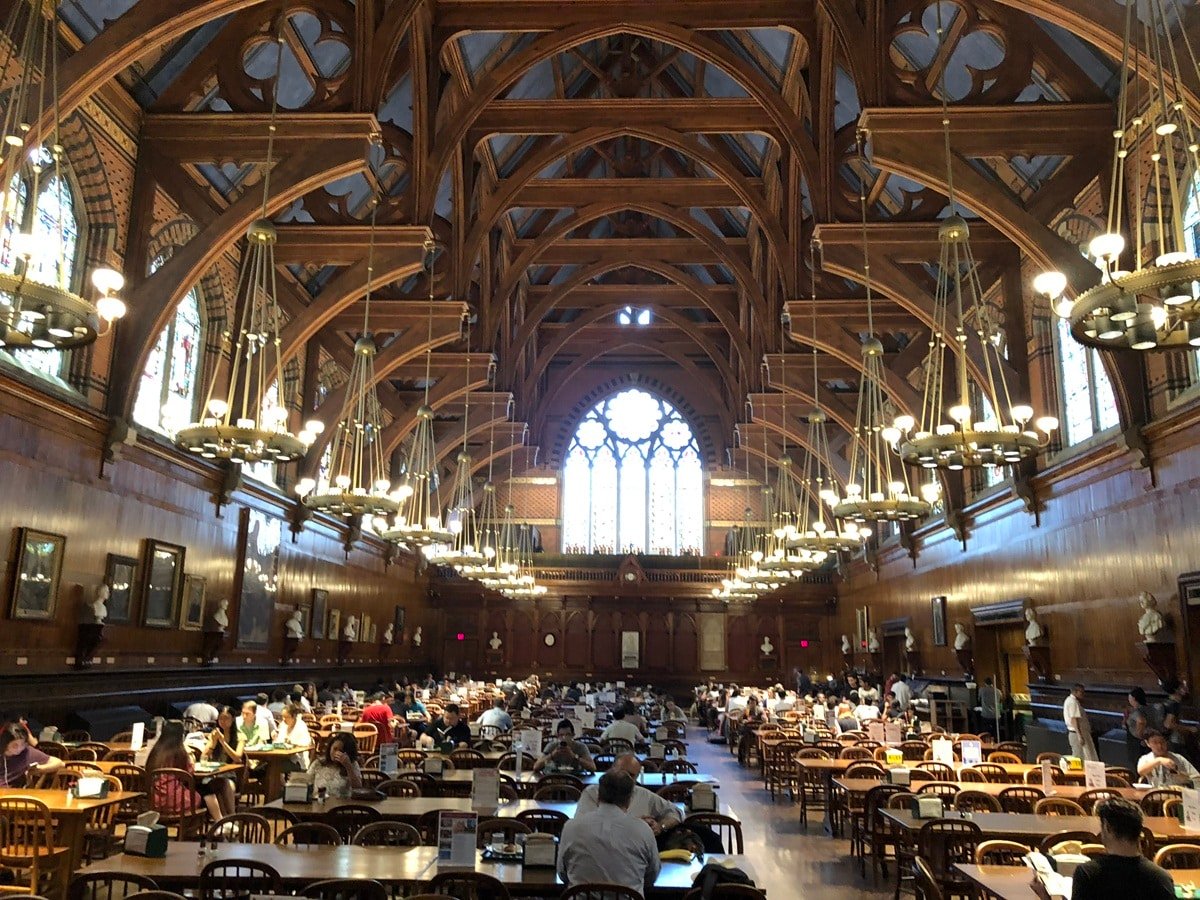

O’Connor plays James Blaine: patriarch of the Mooney family, husband to Terri (Haim), and father to two sons (Sterling and Jasper Thompson), all of whom seem unaware of the way he wanders off on family outings at the Framingham Museum of Art (filmed at IM Pei’s Cleo Rogers Memorial Library in Columbus) only to come back with a priceless totem in his glasses case. The museum’s lax security measures embolden Mooney, son of a judge (the ever-formidable Bill Camp), to hatch a plan to steal four paintings by Arthur Dove, known as the first American surrealist. He rounds up a team with a loan from his mother (a watchful Hope Davis) to whom the art school dropout lies, claiming the money is to help with a proposed architectural project. We will later see him stowing the work in a pig sty (a remarkably elongated sequence even by this film’s own standards) with seemingly no plan of where they will go next. Most of this is dealt with in the opening half-hour, Reichardt seemingly more interested in the realities of what comes next: how the local mob will react and Mooney’s lack of planning will lead to his unravelling.

Watching the film on Friday, I was reminded of the moment in The Parallax View when Warren Beatty pulled up to LAX in his Ford Torino, breezed through a metal detector and onto a commercial airliner without ever producing a ticket. Such public trust, or naivety, was on the way out at the beginning of the 1970s, a feeling that gives Reichardt’s film (where the Vietnam war looms) an unusual charge, casting Mooney’s actions––putting his family’s present and futures at risk for his own vague pursuit of God knows what––in an even more selfish light. Is there something being said here about the current state of the nation, a culture of self-interest, the loss of an ideal? Perhaps, though Reichardt wisely leaves much to the imagination. The film gradually makes its way towards a denouement that combines some final loss of principles with public unrest and poetic justice.

With The Mastermind, Reichardt has made a unique film, even amongst similarly cryptic genre exercises. You wait and wait for the moment of catharsis, the existential monologue in the third act that will cast our dubious protagonist’s actions in a grand, ineffable light––perhaps some statement on crime as a kind of performance art, or the other way around. Yet even this is conspicuous for its absence. Such futility will be alienating to certain audiences. I left the cinema gripped and unusually rattled.

The Mastermind premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival and will be released by MUBI.

The post Cannes Review: In Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind, Crime is a Losing Game first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Stephen King’s ‘Never Flinch’ Is a Messy Exploration of Feminism and Addiction [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Screenshot-2025-05-27-085722.png)

![The Studly American [APARTMENT ZERO]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/apartment_zero-poster.jpg)

![Money Changes Everything [GREED on video]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/greed-3leads.jpg)

![The Sun Also Sets [The Films of Nagisa Oshima]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/boy-flaginside.png)

.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)