J. Hoberman on 1960s New York, Protests, Alternative Press, and Sinners

To paraphrase Margaret O’Brien in Meet Me in St. Louis: Wasn’t I lucky to come of age in my favorite city? For one thing, my impressionable undergraduate years fell during J. Hoberman’s tenure as lead film critic of the Village Voice, and his approach––which I would characterize as treating movies as artifacts or maybe symptoms […] The post J. Hoberman on 1960s New York, Protests, Alternative Press, and Sinners first appeared on The Film Stage.

To paraphrase Margaret O’Brien in Meet Me in St. Louis: Wasn’t I lucky to come of age in my favorite city? For one thing, my impressionable undergraduate years fell during J. Hoberman’s tenure as lead film critic of the Village Voice, and his approach––which I would characterize as treating movies as artifacts or maybe symptoms of overlapping artistic, social, and political zeitgeists––was tremendously influential to me, as it has been to other critics attempting, for better or worse, to locate art in the world and maybe understand the world through art. A wag once observed that Hoberman’s year-end top 10 list was the rare opportunity to find out which movies he actually liked, but I can’t imagine having received a better education than the encouragement, implicit in his work, to set aside aesthetic hierarchies in favor of networks of associations and draw my own conclusions.

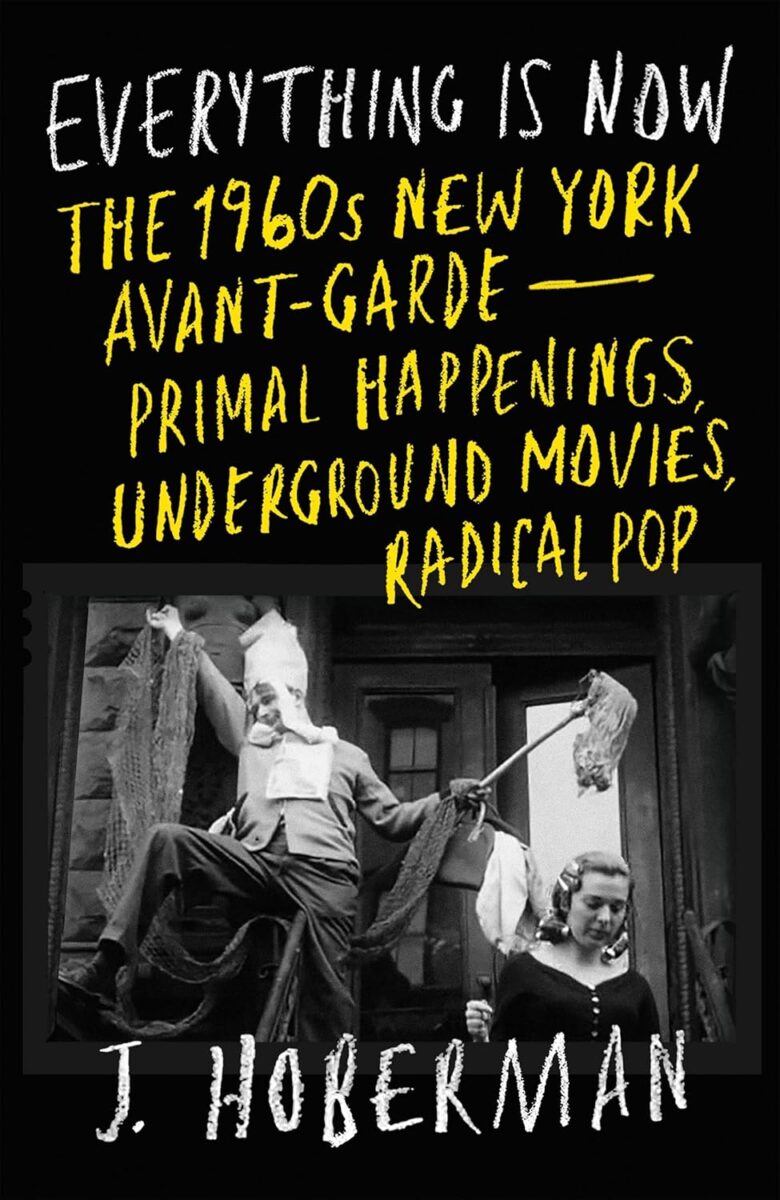

Hoberman’s new book, Everything Is Now, is a history of a time in New York City when those networks were especially dense. Hoberman re-immerses the reader in the underground art movements of the 1960s: trashy and camp films by Jack Smith, fourth wall–smashing plays by the Living Theater and the Performance Group, free jazz by Ornette Coleman, nude Happenings by Yaoyi Kusama, Pop and Op art, agit-folk, psychedelic light shows, and on and on. The book is divided into “Subculture” and “Counterculture,” moving chronologically through the decade and showing, especially as the Vietnam War heats up and youth culture emerges as a dominant force, how the oppositional aesthetics of alternative artistic movements informed the confrontational tactics of alternative political movements. Local radical performance becomes national revolutionary spectacle by leveraging the new mass media. Unsaid, but to me implicit, is that avant-garde “superstars” were innovators and early adopters of the techniques and technologies that would subsequently enable the rise of Reagan––a story Hoberman told in his “Found Illusions” trilogy of books The Dream Life, An Army of Phantoms, and Make My Day, chronicling the Cold War and American myth as refracted by and experienced through its movies.

For the duration of Everything Is Now, though, lower Manhattan seems to still be, well, a village––a teeming social ferment in which art, variously thrilling and enervating but always on the cutting edge of something, is experienced live and promoted through (and debated in) the alternative papers making the scene week in and week out. The book is an expression of gratitude for the more intimate (and much more affordable) city that the author, like all New Yorkers of every age, once knew. The teenage author pops up throughout as a precocious Voice reader and gatecrasher of Dylan concerts, but the book belongs to marginal figures, hangers-on, and scene legends, both artists and their chroniclers. Characters emerge and recede, old bylines drop out and new ones pop up, movements are hip and then passé; the city remains. The book is on shelves now; a film series featuring films discussed therein––including experimental classics, rare performance documents, and a simultaneous projection of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo and Robert Kramer’s Ice––runs June 20 – 24 at Anthology Film Archives, one of the East Village’s few remaining connections to the world of Everything Is Now.

I spoke to Hoberman earlier this week.

The Film Stage: I suppose we should start with political theater and public protest. Because yesterday, a candidate for mayor was roughed up and arrested by feds while escorting New Yorkers out of immigration court. Video of the incident was immediately circulated via social media and published on the Times website; a spontaneous rally developed downtown ––

J. Hoberman: I was there.

Well, certainly this would warrant a paragraph in Everything Is Now 2025. I’m curious what parallels you see between what you write about in the book and what you observe––or how you participate––today.

It was radical when––I think it was Abbie Hoffman, or some other Yippie––said, after Chicago ’68, “the whole world is watching.” Because the whole world wasn’t really watching––it wasn’t televised live––but the idea that a street demonstration could become globalized, an immediate event, was a powerful realization. Of course, the slogan was wonderful too. I don’t know whether things have the same impact today. Certainly the idea of pop-up rallies is completely due to the Internet. It makes it possible to have an almost instantaneous rally to which all these political figures showed up. That was the thing that amazed me the most—also, it was a good-looking crowd. I don’t know how else to say that.

At the same time, things seem even more Balkanized, so it’s a paradox. You can rally your––there’s this term that Vonnegut used in Cat’s Cradle, your karass, your granfalloon––you can reach your group, but does it have any impact beyond that?

The point that I was making in the book about the 60s was that happenings, as they were called, was a new kind of performance that moved out from lofts and galleries into the street, so that you had somebody like Abbie Hoffman, who understood how you could take these seemingly absurd events and use them to make political points. I don’t know that that can have the same impact now. But, you know, maybe I’m wrong.

In general, are you interested in Instagram, TikTok, Twitch as art mediums or media artifacts or theaters of personality?

I did sign up for Bluesky because I wanted to promote my book, but also I kind of enjoy that kind of contact with people. Although, again, I realize there’s a specific audience you’re talking to. In terms of other social media, I’m more interested in things that people do with their phones. I have a seminar at Columbia in documentary [that I teach] once a year, and I put a big emphasis on people making films with their phones and encouraging them to do that. But that’s not exactly new. The phones only came into existence maybe 15 years ago but it seems already like old-fashioned technology, that people would make movies on their phones and then upload them to YouTube.

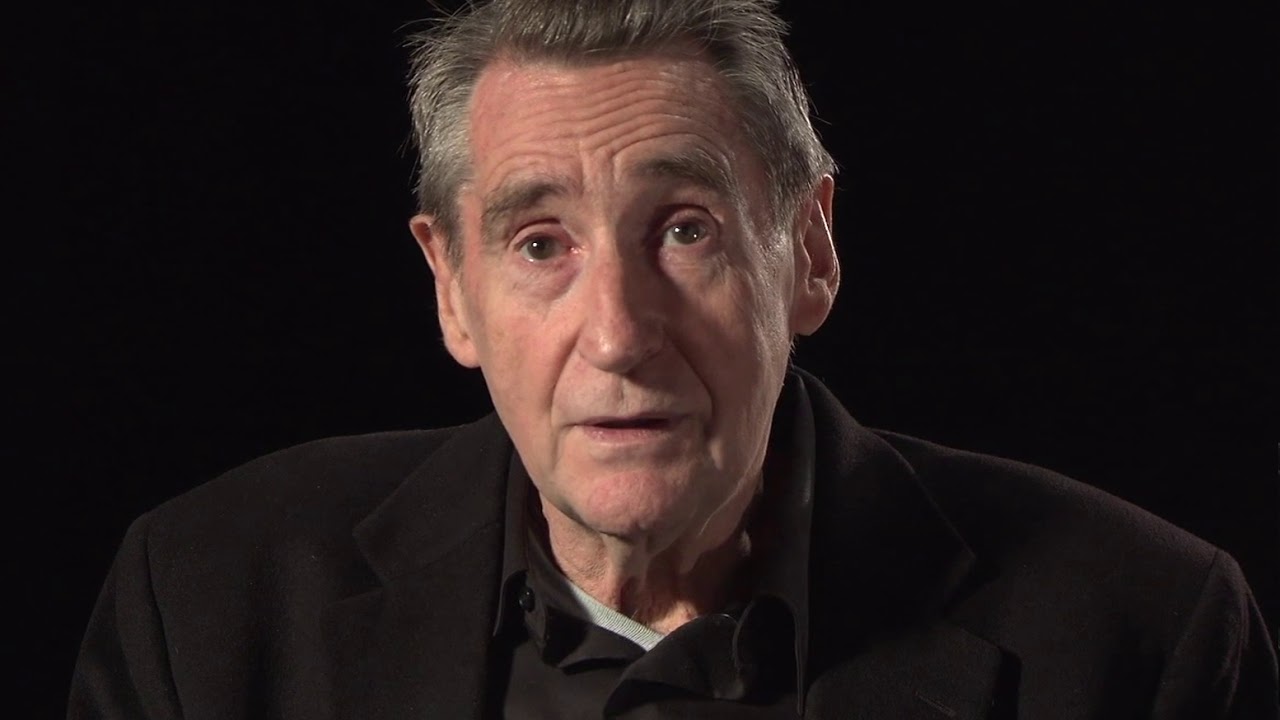

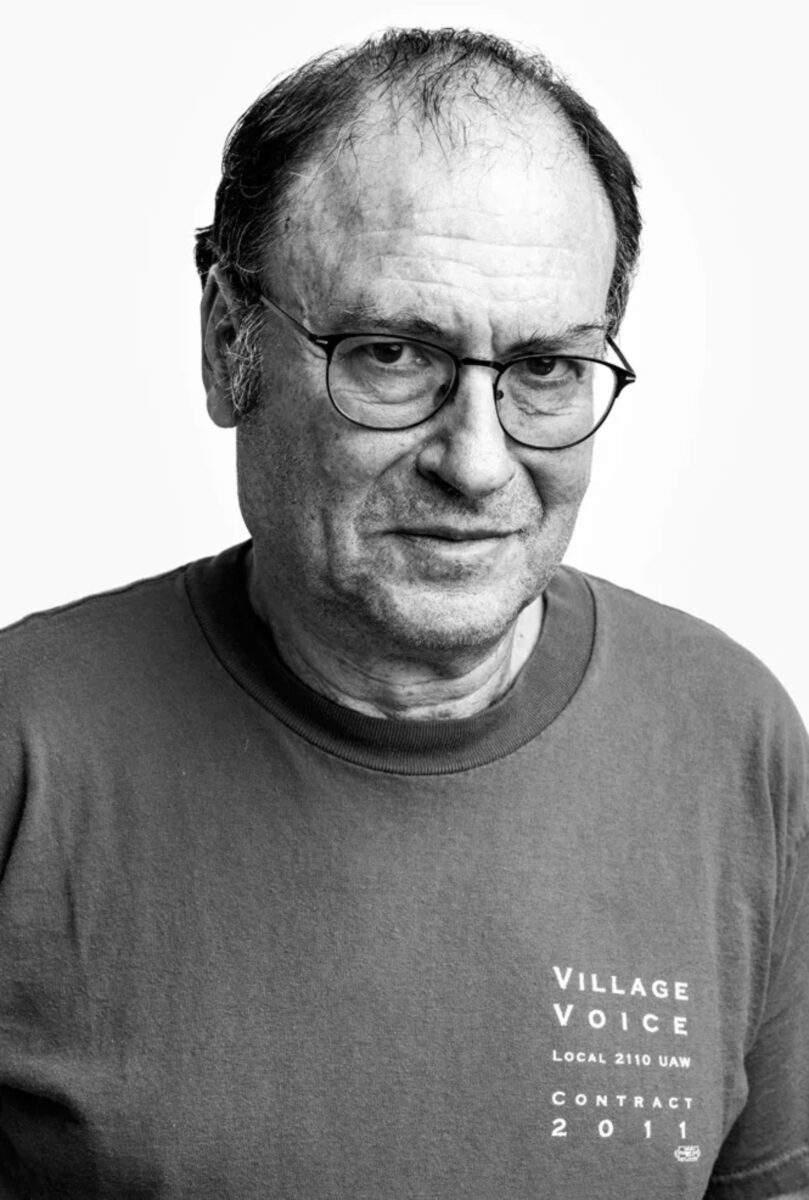

J. Hoberman

A theme of the book is the way techniques of experimentation––spontaneity, confrontation, bad taste––inform first art happenings and then protests, be-ins, even bombings. There’s an awareness of how stuff will play to a mass media rather than an in-person audience. And the transition from scenes to screens is the story of the period during which you were a regular reviewer. For that reason I’m curious if you see this book in conversation with the Found Illusions trilogy, with the rise of Reagan.

I certainly see it in conversation with The Dream Life, since it’s covering the same material. In a way, this book was a reaction. I was tired of writing about Hollywood movies; I felt that I had said what I had to say, and I wanted to go back to something of more personal interest.

What I was trying to get at is how a polity or collective entity expresses itself through the contributions of individuals. Again, that can be extrapolated to the present time––I don’t know that I would have the same personal investment in it, although I was thinking about [the 60s] for the last three or four years and now I’m back in the present, so I could have some other thoughts. Those have been, as I said, mainly to do with citizen journalism. As opposed to performative TikToks, which I’m aware of, although I don’t follow it. There was that comedian who was so great during COVID, making fun of Trump. That was both underground and viral at the same time. I don’t know what became of her, but everybody was watching her. She used to lip-sync.

To talk a little bit about the personal aspect––being somebody whose own youth was misspent reading and writing for the alternative press––I wanted to ask what it was like to read, or reread, the Voice and other papers for this book. How differently does the first draft of history read in hindsight?

Well, I’m glad you mentioned that, because I was going to say that, though people may have been playing to a mass audience, they still communicated through the alternative press.

I couldn’t have written this book without the alternative press. The Voice was the basis for virtually all the information about things that were going on in terms of underground film and performance and even community activism for the first half of the ’60s; and when the Voice became semi-established, the East Village Other and then Rat and then, nationally, all sorts of other papers picked up the slack. Because there was no video, in any real sense, until the 1970s or so, the things that people wrote describing these events are what we have. There are sometimes some photographs, but that’s really it. So I felt tremendous gratitude.

I read these papers, but in rereading them I came to a belated appreciation of some of the writers. Because when you’re 19 or 20 years old, you think you know it all––it takes a lot to impress a 20-year-old. There was plenty of nitpicking that I could have done at the time, but I no longer feel that way. And having spent the better part of my life writing for a weekly, I can read these earlier ones now with a real understanding of how a paper gets put together, so that increased my appreciation too. But as a means of communication within the counterculture, those papers were invaluable. It’s just remarkable how much information people got out to each other.

There are a lot of bylines attributed in the book. Some of the writers are people you would have read at the time, some are forgotten, and some still read today. Some eventually became your colleagues, some maybe rivals. Did you discover anybody, or did any writers rise or fall in your estimation?

Nobody really fell; if they’re in the book, it’s because they wrote something [useful]. There are some people––there was a woman who wrote for EVO, named Lita Eliscu. I remember at the time I didn’t think she was a particularly good writer. She covered some things that I was interested in, so I certainly knew her byline. But revisiting this, 55 years later, I was impressed by her journalistic chops. That was maybe more important in the alternative press, at least the post-Voice alternative press, than writing.

The Voice was always a writer’s paper. Although Jonas [Mekas] was not a great writer, he’s something else. Jill Johnston––that’s the other one who was so incredible in terms of what she was present for and wrote about––had written quite normally, so to speak, when she was reviewing for art magazines. And then she just developed this other style for writing in the Voice, which at the time I wasn’t that impressed with. But now I think that a great deal of the history of the period exists thanks to her.

You’re using advertisements, listings, reviews, recaps, essays about artworks; some are permanent and some are impermanent. There’s films and lost films, physical artworks and live performances. To what extent is the scope and emphasis of the book dictated by the extant record versus by your own judgment and priorities? Is there stuff you had to really work to get in there? Stuff you wish you had more of?

The book kept expanding as I discovered things. The first thing I thought of was that maybe I should take a dozen artists and do a kind of collective biography. I decided against that for a number of reasons––one was that I thought it was insufficiently collective; I wanted to talk more about the city, or a milieu.

There are people who I came across who I’d never heard of, who I put in the book, that I would have loved to have known more about. But, you know, there were people who just disappeared, and there’s no real record. There’s an actor, Jeanne Phillips, for example. I mean, I knew her name. She was in Jack Smith things, and in plays and so on. And she was a woman of color, which was unusual in that scene––although not unheard-of. I was finally able to piece together that she had once been some kind of city worker and then got involved in this crazy fringe theater. I’m thinking, “Who is this woman?” I really would have been curious to talk to her.

And there were artists who turned up, and I might have been aware of them––someone like Jackie Cassen, who was into mixed-media light shows. But it wasn’t until I was working on this book that I realized she was one of two or three people who created the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Warhol was like the Thomas Edison of the scene, just drawing on other peoples’ stuff––it’s not to take anything away from him, but he’s an impresario. So by the time I figured this out about her, it turned out she had just died. She’d been living on Staten Island. I could have interviewed her if I had thought of this a year or two earlier.

The converse of this is: what kind of rules did you set about underground figures who became nationally significant? It seems like you had to maintain an idea while writing about who counts as within the scope of the book and who doesn’t, and decide how you manage somebody like Dylan, moving between the Village and Woodstock, manage Warhol’s films versus his visual art, manage the Velvet Underground as a rock band versus as Factory affiliates.

You mention probably the three most critically examined figures in the book. I wasn’t sure that there had ever been a book in which Warhol and Dylan were co-equals. But on the other hand, I didn’t want them to dominate. There are probably 12 or 15 figures who are in it from beginning to end. Yoko Ono shows up very early and she’s there at the end, and it mainly has to do with her period as a Fluxus fellow-traveler rather than as the wife of the biggest pop star in the world.

I wasn’t going to ban stars, but neither did I want to make them so central. The idea of conjoining Dylan and Warhol, which happens right at the center of the book––I’m interested in the protest scene that Dylan attached himself to, just like I’m interested in the proto-Pop scene that Warhol attached himself to. Both of these guys––from Minnesota, Pittsburgh––they come to New York and they’re like sponges. That’s their genius: they’re capable of absorbing things around them and creating their own synthesis. But I wanted it to be clear that this couldn’t have happened in a vacuum. The whole idea of rugged individualism is kind of abhorrent to me.

This is the story of how a certain time and place and people produced this art, and the story of that time and place and people as told through the art that it produced––which I think is a theme in a lot of your criticism. In this book, you taxonomize movements, you conceptualize artworks, you juxtapose them with one another in suggestive ways. A lot of the book is organized by these lickety-split transitions: this other art event was happening a block away; this film is covered in the same issue of the Voice. Both are a few days before or after this or that political event. When laying out the book through these coincidences, are you setting out to link artworks and events to each other and then deliberately finding a hook, or are you following the chronology and then discovering the echoes and resonance?

Well, let me tell you how I work. I need a chronology; it’s very important. I have a rough idea, but to really start writing, I need a chronology.

But even though I need a chronology, I don’t write in a chronological fashion. I learned as a journalist with a byline to do the easiest stuff first, ’til you have something or else come up with a lede and come up with a kicker and then figure out how to make it work. Andrew Sarris used to sit there and write in a completely linear fashion. I can’t do that. And so, in the course of working on different parts of the book––going from here to there and back––the juxtapositions would give rise to ideas. I’m not going to say that I was functioning like Burroughs making cut-ups or an Abstract Expressionist painter, but the process of assembling it was very stimulating.

You mention Burroughs––I do think of it as a little bit aleatory. And I know that when you’re lecturing, one of your preferred pedagogical tools is the double projection: superimposing these movies and seeing how they line up. Is there a parallel between “let’s research what was happening on this block this week” and “let’s play these two movies on top of each other and see what emerges”?

I hadn’t thought of it that way, but it’s basically montage: meaning is constructed from the juxtaposition of things. There’s some Jungian quote that somebody told me in college, which I’d never really been able to track down––something to the effect that the universe loves a coincidence.

When you show two movies together, you can’t predict what’s going to happen. But something interesting always happens. In the same way, it’s just intriguing to me that certain things would have been going on simultaneously or almost simultaneously. They may or may not have been connected. That’s part of the reason for the title of the book: I wanted to create this overwhelming sense of the present, and [this impression of] seemingly simultaneous events was part of it.

A close reader of the book kind of chastised me, or thought that I should have been more judgmental in terms of taste. But that wasn’t my intent. I’m always interested in reception, in how these things were perceived at the time, which––again––is why the alternative press is so crucial.

There have been some excellent oral histories––Gerd Stern gave an amazing oral history [From Beat Scene Poet to Psychedelic Multimedia Artist: 1948 – 1978]. So you get what their subjective view is. There have been some good memoirs and stuff, but that’s something different too.

There were certain films or exhibitions or theatrical pieces which seem to me to be landmarks, just like there were certain artists who seem to be undeniably important––although certainly these things changed. My whole view of Kusama changed while I was working on this book, for example. I remember at the time I just thought she was some kind of crazy exhibitionist, and she was, but there’s a significance to what she was doing,

It’s interesting that she’s like such a viral figure now, because you depict her as inventing virality, a little bit.

She moved from the art world into the counterculture, which is not a move that too many other people made. But anyway, between the landmarks I’m always looking for stuff to fill in the background––all this anecdotal information to solidify the past.

To speak to solidifying the past: a few years ago, I was in a bar with a few other colleagues talking about, I don’t know, what would define “Obama-era cinema” or the “Trump canon.” And a friend and colleague just sighed and said something like, “Boys love talking about who was president when a movie came out.” It made me think of the Voice 50th-anniversary essay you wrote, which I read in college, where you mentioned that “the ideological analysis of mainstream movies, becoming a house specialty after Ronald Reagan was elected president.”

That’s a very casual way of describing an approach that seems to have trickled down––there’s an LARB series right now about Biden-era cinema; people regularly parse the values of a given Disney animated film, whether they’re progressive or reactionary, at the expense of any formal or aesthetic analysis. Are you conscious of the influence of that house style?

It’s sort of dismissive to say, “Been there, done that.” I did write something about Obama cinema, but it was very, very circumscribed. There were obvious ways in which movies organized themselves around him. But the movies are just not as important as they used to be. Hollywood reached its peak with Ronald Reagan. That’s really when the whole ethos entered into everyday life––even though, from another standpoint, the movies had ceased to be the dominant popular form. We’re past that now. Trump is something completely different. I got into that a little bit at the end of Make My Day, in part because my wife would say, “Why aren’t you writing about what’s happening now?”

You know, I was very happy as the second-string critic at the Voice. Andrew Sarris would never believe this, but I was perfectly content not having to review movies by Steven Spielberg and so on. But then he got ill and I had to take the job, and so to make it interesting for myself, I did these ideological readings. In a way, I’m glad––I would have lost my mind when Marvel came in, but that was after I lost my job, so I didn’t have to contend with that.

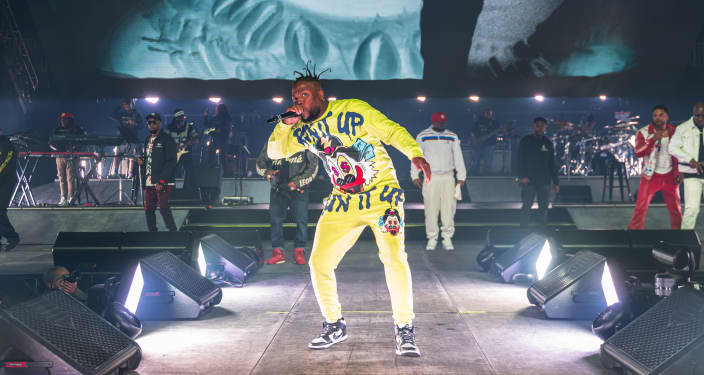

People sometimes ask me if I’m going to do something on Biden or Trump. I’m not. There’s something else going on. Maybe I can contribute to it, maybe I can’t. I don’t watch enough television to be able to say much about that. And I’m a civilian––I go to see movies that I want to see. Sometimes there’s something that just sounds so interesting––you know, like Sinners––that I go to see it. That one I could have written about.

What’d you think?

I thought it tapped into this wealth of under-leveraged material. It was so great to see a movie set in the Mississippi Delta in the 1930s, with all these allusions. I loved that big, anachronistic dance number. Then it became too Tarantino-like. The vampire thing was not without interest, but it seemed kind of obvious to me. I would love, for example, to know what Arthur Jafa makes of this movie––he’s from Clarksdale. Clearly this guy [Ryan Coogler] is fascinating, is a major filmmaker. It’s the most interesting Hollywood movie I saw this year, but I really don’t see all that much.

Maybe just a sentimental question to close on. In the book, you give a lot of exact street addresses for venues, and it’s cool to realize, say, “Oh, that’s KGB Bar now.” As a New Yorker this is a hobby of mine: I can eat at Szechuan Mountain House on Saint Marks and think to myself that this is where they had the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. But it must be different for you to pass the former location of Max’s Kansas City on the way to the Criterion offices, given that you actually went to Max’s Kansas City. Are you sentimental about any long-gone places?

Oh, sure. Yes, I miss the New York of my adolescence and early adulthood. But, you know, this is New York. I felt that, by giving the addresses, I was creating little monuments. I was very struck by the fact that in Paris, you walk around and they’ll tell you, “Oh, Baudelaire lived here.” They’re so conscious of their past. And in New York there’s nothing like that. I feel like these lofts, these buildings, when they [still] exist, should be acknowledged for what they were. So that was my way of making a mental map. And I’m glad people notice; I’m glad people enjoy it. I was bracing myself for my editors saying, “Why are you doing this?” It was an eccentricity that they let pass. They were very good.

Everything Is Now is now available and J. Hoberman Selects: Everything Is Now is underway through June 24 at Anthology Film Archives

The post J. Hoberman on 1960s New York, Protests, Alternative Press, and Sinners first appeared on The Film Stage.

![‘The Descent’ Official Novelization Coming Soon from Titan Books; Read First Chapter Now [Exclusive]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/descent-shauna-2.jpg)

![No Stars: A Must-See [THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/1990/03/ThePlotAgainstHarry-300x168.jpg)

![The Nasty Woody [ANYTHING ELSE]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/anything-else.gif)

![American Airlines Slammed By Elite Passenger Forced To Fly Economy While Pilots Relax In First Class [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/amercan-airlines-737-first-class-seat-pair.jpg?#)

![United Flight Attendant Leaves Risqué Note for Miley Cyrus’ Ex—”I Was Shakin’ Like a Stripper” [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ua-fa.jpeg?#)

![[Podcast] Problem Framing: Rewire How You Think, Create, and Lead with Rory Sutherland](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/rort-sutherland-35.png)