Women’s Work: On Mikio Naruse

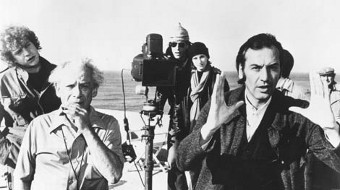

Repast (Mikio Naruse, 1951).Mikio Naruse was radical in his dedication to the mundane. Whether employing the devices of melodrama or abandoning plot almost entirely, he maintained a lucid, unsparing focus on the everyday routines and pressures, compromises and disappointments that quietly erode his characters, the way drops of water wear down a stone. Naruse made films about women’s bruising emotional lives, but above all about women’s work: the thankless domestic chores of wives, the constrained roles of geisha and bar hostesses, and the various labors of maids, shopkeepers, bus conductors, office workers, farmers, and even artists.Naruse’s genre was shoshimin eiga, “common-people dramas” about the pinched and precarious world of the lower-middle classes. His characters tend to live in cramped houses with scuffed tatami mats and battered shoji screens. Among the pleasures of films such as Mother and Lightning (both 1952) are the weathered texture and raffish shitamachi atmosphere of working-class neighborhoods with their narrow, dusty alleys, old wooden houses, and cluttered storefronts. The director himself, born in 1905, grew up poor, and his portrayal of these areas is unromanticized but not without tenderness. He loves street peddlers, who are always passing in the background of scenes with their wares in carts or strung on bamboo poles; the cries of itinerant knife-sharpeners; and the music of strolling buskers. New York’s Japan Society hosted the first retrospective devoted to Naruse in 1973, four years after his death; ever since, he has had a keen following among cinephiles, but the breadth of his work has remained elusive. This year brings another chance to explore his vast filmography—he directed around 90 features between 1930 and 1967, going from silent films to color and CinemaScope. The celebration, which includes related programs in several American and Canadian cities, begins with a 30-film retrospective at Japan Society and Metrograph, “Mikio Naruse: The World Betrays Us.” The title is drawn from a statement that sums up the filmmaker’s legendarily pessimistic outlook: “From the earliest age, I have felt that the world we live in betrays us.”Wife! Be Like a Rose! (Mikio Naruse, 1935).At fifteen, the orphaned Naruse went to work as a prop assistant at Shochiku, one of Japan’s oldest studios. After working his way up through the ranks, he graduated to directing in 1930, and made two dozen silent films (five are known to survive). In 1935, he left Shochiku for P.C.L., the precursor to Toho, where he made his first sound films, and where he would spend the rest of his career. His breakthrough was that year’s Wife! Be Like a Rose!, which topped the Kinema Junpo magazine poll and became the first Japanese talkie shown in New York. Like many of his prewar films—the subject of a series at this summer’s Cinema Ritrovato festival—it is set in a world uneasily divided between tradition and Westernized modernity. The protagonist, Kimiko (played by Sachiko Chiba, who would be married to Naruse from 1937 to 1940), is a confident, modern working girl. She even playfully tries thumbing a ride, exclaiming, “I saw it in the movies!” The light, comic tone of early scenes gives way to a delicately moving family melodrama when Kimiko sets off into the countryside determined to bring back her wayward father, who ran off with his geisha mistress. What she discovers upends her conventional ideas about marriage and propriety.The motif of a transformative journey, often from the city into the country, recurs throughout Naruse’s films, from the silent Apart from You (1933) to the late masterpiece Yearning (1964). His people are so often stuck in ruts that a train ride into the mountains or a day at the seaside can feel like an exhilarating escape. The relief is generally short-lived; Naruse said of his characters, “If they move even a little, they quickly hit the wall.”Apart from You (Mikio Naruse, 1933).Thematically, there is extraordinary consistency throughout Naruse’s long career, but stylistically he evolved by stripping away flourishes. His silent and early sound films use impressionistic montage, freewheeling traveling shots, fast dollies, whip pans, lap dissolves, and sound bridges spanning scenes. By the 1950s, he had developed a mature style of unobtrusive camerawork, naturalistic lighting, and fluid editing. Late in life, Naruse talked about making a movie with no sets or props, just a plain white backdrop, to direct all attention to the actors’ gestures, expressions, exchange of gazes, and relations in space. Naruse considered the late 1930s and ’40s a low period when he was forced to take studio assignments with inferior scripts. These were the years of Japan’s empire, the Second World War, and the American occupation, when government censorship forced filmmakers to uphold one ideology or another. Naruse mostly skirted overt propaganda, making a series of films about traditional performing arts; even th

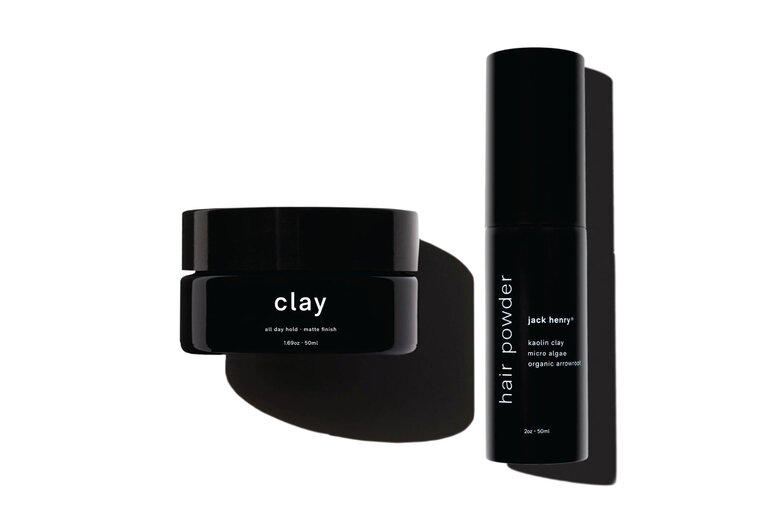

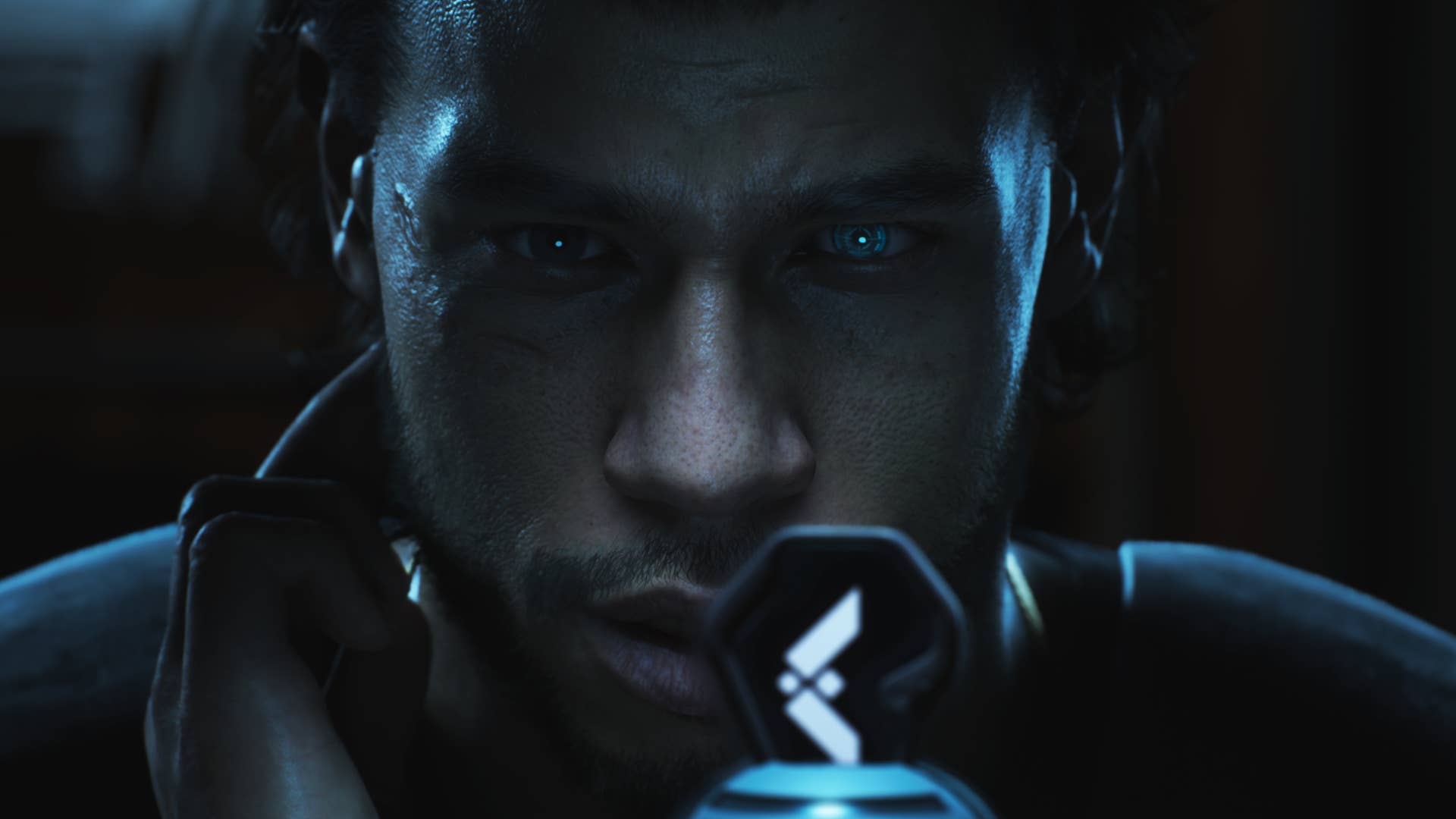

Repast (Mikio Naruse, 1951).

Mikio Naruse was radical in his dedication to the mundane. Whether employing the devices of melodrama or abandoning plot almost entirely, he maintained a lucid, unsparing focus on the everyday routines and pressures, compromises and disappointments that quietly erode his characters, the way drops of water wear down a stone. Naruse made films about women’s bruising emotional lives, but above all about women’s work: the thankless domestic chores of wives, the constrained roles of geisha and bar hostesses, and the various labors of maids, shopkeepers, bus conductors, office workers, farmers, and even artists.

Naruse’s genre was shoshimin eiga, “common-people dramas” about the pinched and precarious world of the lower-middle classes. His characters tend to live in cramped houses with scuffed tatami mats and battered shoji screens. Among the pleasures of films such as Mother and Lightning (both 1952) are the weathered texture and raffish shitamachi atmosphere of working-class neighborhoods with their narrow, dusty alleys, old wooden houses, and cluttered storefronts. The director himself, born in 1905, grew up poor, and his portrayal of these areas is unromanticized but not without tenderness. He loves street peddlers, who are always passing in the background of scenes with their wares in carts or strung on bamboo poles; the cries of itinerant knife-sharpeners; and the music of strolling buskers.

New York’s Japan Society hosted the first retrospective devoted to Naruse in 1973, four years after his death; ever since, he has had a keen following among cinephiles, but the breadth of his work has remained elusive. This year brings another chance to explore his vast filmography—he directed around 90 features between 1930 and 1967, going from silent films to color and CinemaScope. The celebration, which includes related programs in several American and Canadian cities, begins with a 30-film retrospective at Japan Society and Metrograph, “Mikio Naruse: The World Betrays Us.” The title is drawn from a statement that sums up the filmmaker’s legendarily pessimistic outlook: “From the earliest age, I have felt that the world we live in betrays us.”

Wife! Be Like a Rose! (Mikio Naruse, 1935).

At fifteen, the orphaned Naruse went to work as a prop assistant at Shochiku, one of Japan’s oldest studios. After working his way up through the ranks, he graduated to directing in 1930, and made two dozen silent films (five are known to survive). In 1935, he left Shochiku for P.C.L., the precursor to Toho, where he made his first sound films, and where he would spend the rest of his career. His breakthrough was that year’s Wife! Be Like a Rose!, which topped the Kinema Junpo magazine poll and became the first Japanese talkie shown in New York. Like many of his prewar films—the subject of a series at this summer’s Cinema Ritrovato festival—it is set in a world uneasily divided between tradition and Westernized modernity. The protagonist, Kimiko (played by Sachiko Chiba, who would be married to Naruse from 1937 to 1940), is a confident, modern working girl. She even playfully tries thumbing a ride, exclaiming, “I saw it in the movies!” The light, comic tone of early scenes gives way to a delicately moving family melodrama when Kimiko sets off into the countryside determined to bring back her wayward father, who ran off with his geisha mistress. What she discovers upends her conventional ideas about marriage and propriety.

The motif of a transformative journey, often from the city into the country, recurs throughout Naruse’s films, from the silent Apart from You (1933) to the late masterpiece Yearning (1964). His people are so often stuck in ruts that a train ride into the mountains or a day at the seaside can feel like an exhilarating escape. The relief is generally short-lived; Naruse said of his characters, “If they move even a little, they quickly hit the wall.”

Apart from You (Mikio Naruse, 1933).

Thematically, there is extraordinary consistency throughout Naruse’s long career, but stylistically he evolved by stripping away flourishes. His silent and early sound films use impressionistic montage, freewheeling traveling shots, fast dollies, whip pans, lap dissolves, and sound bridges spanning scenes. By the 1950s, he had developed a mature style of unobtrusive camerawork, naturalistic lighting, and fluid editing. Late in life, Naruse talked about making a movie with no sets or props, just a plain white backdrop, to direct all attention to the actors’ gestures, expressions, exchange of gazes, and relations in space.

Naruse considered the late 1930s and ’40s a low period when he was forced to take studio assignments with inferior scripts. These were the years of Japan’s empire, the Second World War, and the American occupation, when government censorship forced filmmakers to uphold one ideology or another. Naruse mostly skirted overt propaganda, making a series of films about traditional performing arts; even these relatively escapist entertainments are streaked with his signature pessimism. Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro (1938) begins as a tart romantic comedy about a male singer and female shamisen player whose success as a duo is threatened by their constant offstage squabbles, plainly sparked by jealousy and unspoken attraction. If this were a Hollywood movie, the outcome would be predictable, but Naruse has far less faith in the power of love to overcome personal failings.

In one of his favorites among his own films, The Whole Family Works (1939), for which he also wrote the screenplay, Naruse quietly undermines militarist and nationalist values. It is a nearly plotless portrait of a large, impoverished clan, as the sons struggle to escape the quicksand of menial, dead-end jobs. Naruse not only depicts the grinding experience of poverty—near the end, the oldest son breaks down in sobs, exhausted from chronic hunger and despair—but also dares to question filial piety, portraying an older generation crushing the hopes of the young. This echoes the theme of his first sound film, the intricately constructed, flashback-studded tragedy Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts (1935), in which a selfish and hard-hearted music teacher exploits her daughters and apprentices, forcing the young women to busk with their shamisens in nightlife districts, where they are ignored, insulted, kicked out of bars, and groped by men uninterested in their musical talents. For women, the profession of entertainer is just another job combining rigorous demands with lowly status.

Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts (Mikio Naruse, 1935).

The shamisen, a stringed instrument with a tone one might call bluesy, is traditionally associated with geisha, who were trained to be both skilled performers and pleasing companions for men. Flowing (1956) probes the complexities of these roles within an elegiac portrait of a geisha house in decline. The powerhouse cast includes three of Japan’s greatest actresses. The regal Isuzu Yamada plays Otsuta, the head of the household, an aging beauty who clings to her proud belief in geisha as paragons of feminine grace and carriers of tradition. But though deeply rooted in Japanese culture and society, geisha were also considered disreputable; viewed by men as sexually available, many relied on the support of “patrons.” Rebelling against the required performance of submissive charm and flattery, Otsuta’s forthright daughter (Hideko Takamine, Naruse’s most frequent star) rejects the family business and tries to make a living as a seamstress. The daily struggles of the house are quietly observed by their maid, played by Kinuyo Tanaka, who subtly reveals the painful effort behind her bright, ingratiating demeanor. She even smiles, humbly and heartbreakingly, as she tells her future employers that her husband and child are dead.

Here, as in the even bleaker Late Chrysanthemums (1954), about an ex-geisha turned money-lender, financial worries are a relentless refrain; life is reduced to a demeaning hunt for cash. This is especially true in Naruse’s many films about bar hostesses, such as Ginza Cosmetics (1951), in which a widowed mother (Tanaka) spends her days doing housework and cajoling deadbeats to pay their bar tabs, and her nights fending off salarymen’s propositions and listening politely to caterwauling drunks. She is teased with a glimpse of something better when she meets a man who quotes poetry and shows her the constellations, just as the heroine in the enchanting Morning’s Tree-Lined Street (1937) gazes at the moon behind the clouds, longing for something beyond the tawdry life of a hostess. With its brisk, jazzy style, Depression-era mood, and crew of sassy girls, Morning’s Tree-lined Street could almost be a Warner Bros. pre-Code movie. But only in Japan would a romantic spa weekend turn into an invitation to double suicide. This time, the journey’s promise of escape is even more illusory than usual, a dream that turns into a nightmare.

Top: Morning’s Tree-Lined Street (1937). Bottom: When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Mikio Naruse, 1960).

For geisha and bar hostesses, femininity is a performance—and hard labor. The ultimate distillation of this theme comes in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960). With its cool jazz score and the neon signs of Ginza bars shimmering in widescreen black-and-white nocturnes, the film has a beguiling surface, but a desolate heart. Keiko (Takamine), who works as the head hostess or “mama-san” at a bar, wears modest kimono instead of flashy western clothes, and the rumor that she put a written vow never to love again in her late husband’s funeral urn makes her an object of romantic obsession for the bar’s sympathetic, streetwise manager (Tatsuya Nakadai). Here and elsewhere, Naruse’s films express deep ambivalence about the traditional ideals of Japanese womanhood: devotion, self-sacrifice, purity. They harbor, like Nakadai’s character, nostalgia for values lost amid a crass, money-grubbing modernity, but also recognize what it costs women—and even men—to uphold such ideals.

When a Woman Ascends the Stairs perfectly illustrates Naruse’s slow-burn approach to melodrama. He establishes the quotidian rhythms of life—structured here by the recurring motif of Keiko reluctantly climbing the stairs to her workplace—and methodically reveals the undercurrent of humiliating desperation beneath the façade of beauty and cheerfulness that the hostesses are forced to maintain. There are no big plot twists, just a steady accrual of small indignities, a muffled buildup of emotions that are tamped down until they can no longer be contained.

For widows and single women, life is a perpetual struggle to make ends meet; but Naruse paints an even grimmer portrait of marriage in a suite of films including Wife (1953), Husband and Wife (1953), and A Wife’s Heart (1956)—the titles alone convey a sense of limited options and crushing sameness. Two of his best marriage films star Setsuko Hara, and it is something of a shock to see the serene beauty, whose angelic smile graced many of Yasujiro Ozu’s films, playing a disgruntled wife who complains about the domestic drudgery and emotional deprivation of her life, as she does in Repast (1951). This formal term is a curious translation of the film’s original title, Meshi, a casual, almost rude, word for rice (and hence a meal), akin to “grub” or “chow.” When her husband grunts “I’m hungry,” Hara’s character retorts that he never speaks to her except to demand food. We watch her realize, crushingly, that her life has been reduced to feeding and serving a man who offers little in return.

Sound of the Mountain (Mikio Naruse, 1954).

In nearly all of Naruse’s marriage films, the indifferent husband is played by Ken Uehara, a one-time matinee idol who, in middle age, specialized in playing the coldest of cold fish. He is particularly insensitive in Sound of the Mountain (1954), but here Hara’s character gets some support from her husband’s family, who openly discuss their unhappy union, including his affairs and her choice to have an abortion. (That Japanese cinema could refer openly to these subjects, along with prostitution and rape, but rarely showed on-screen kissing, while Hollywood in the fifties blushed to even show a double bed but made a trademark of stars locking lips in close-up is a fascinating study of cultural difference.) The bluntness with which Naruse’s characters speak to family members can feel brutal. Lightning climaxes with a bitter, flaying scene in which a daughter tells her hapless, much-married mother that she wishes she’d never been born, and that “you had us without love, like a cat.” Yet afterward, mother and daughter stroll off together in the post-storm calm.

Lightning and Repast are two of six films Naruse directed based on the writings of Fumiko Hayashi. The last, A Wanderer’s Notebook (1962), was adapted (by the successful female screenwriter Sumie Tanaka) from Hayashi’s first book, an autobiographical novel that recounts her grueling rise from being the child of itinerant peddlers through years of abject poverty and bad relationships, before she finally turns this life into the subject for a breakthrough literary success. Naruse may have been drawn to Hayashi partly for her unvarnished descriptions of existence on the margins: In the film, she is criticized by fellow writers for her squalid subjects, her poetry called “naked” by one, and compared by another to the contents of a dustbin.

Hayashi’s unflattering self-portrait is matched by Takamine’s performance in the lead. She makes Fumiko boldly unprepossessing: slouching, frumpy, and glum. As she bounces between menial jobs and stints as a bar hostess, she falls for handsome, selfish men who treat her horribly, explaining that she “can’t help loving men, even if they beat me.” Hayashi is considered a feminist writer, but she and Naruse both confront the oppression and exploitation of women without idealizing their female characters, and rarely suggest much hope for change. What they do offer is too rare in cinema: women who are neither demonized nor put on pedestals, but allowed to be fully human.

Floating Clouds (Mikio Naruse, 1955).

The most celebrated of Naruse’s Hayashi adaptations, Floating Clouds (1955), is a romantic melodrama that can be read as a critique of its genre, exposing the self-destructive pathology of romantic illusions. It follows a woman (Takamine again) who clings persistently to a man unwilling to commit to her. The cold, chaotic, hardscrabble environment of postwar Japan is contrasted with the dreamlike memory of a wartime romance in the tropical jungles of Indochina; both main characters are mired in self-pity and paralyzing nostalgia. The man is played by the elegant Masayuki Mori: If Uehara is the icy, withholding husband in Naruse’s marriage films, Mori is the gentle, melancholic, but ultimately weak and disappointing lover. Men in Naruse’s films are not always entitled jerks, but they are almost always ineffectual, stunted and perhaps even infantilized by a lifetime of being waited on and propped up by women.

His contemporary Ozu may have cornered the seasons, but Naruse made weather his own, with Floating Clouds, Summer Clouds (1958), Scattered Clouds (1967), Sudden Rain (1956), and Lightning. This is not merely a matter of titles, but of visceral physicality. The drenching rain and suffocating humidity at the end of Floating Clouds, when the heroine follows her beloved to a famously inclement island despite her ill health, feels fitting: She winds up in a land that is always weeping. Naruse’s characters are continually reacting to heat or cold: huddling over hearths in winter, warming their hands on smoldering coals; in summer, fanning themselves and mopping their necks, eating ices and melons while children play with sparklers in the street. Weather, like so much else in these films, is inescapable.

Untamed (Mikio Naruse, 1957).

Naruse made few period films, but one delightful exception is Untamed (1957), set in the Taisho era (1912–26), a time of rapid modernization and openness accompanied by a short-lived democratic government. It is also one of the most optimistic and bracingly feminist of all his works. Over the course of the film, the heroine’s journey from downtrodden wife to emancipated businesswoman is paralleled by the appearance of new technologies—trains, telephones, Victrolas, and movies.

Oshima (Takamine) is introduced as the new wife of a canned-goods merchant (Uehara, reptilian as usual) who soon divorces her, following a miscarriage during a violent argument. “Always a hard worker,” she goes to the mountains to toil as a maid at an inn to pay off her brother’s debts: waiting on guests, polishing floors, scrubbing laundry in the river. There she falls in love with the married manager (Mori, appealing but spineless as ever). Back in the city, she becomes a seamstress, learns to use a sewing machine, starts her own shop tailoring Western clothes, and promotes it by riding a bicycle in a European-style dress and hat. Determined and savvy, Oshima is also unruly and pugnacious, engaging in several knock-down, drag-out brawls and turning a hose on her second husband (Daisuke Kato) when he slacks off work, then insults and slaps her. She is “just like a man,” other characters say with a mixture of disdain and awe. And for once, the film seems to hold a reward for this long-suffering woman: not only independence, but the delectable young Tatsuya Nakadai, in one of his earliest film roles as the shop assistant she promotes to partner, and perhaps more.

Hideko Takamine was indispensable to Naruse’s films because of her unadorned honesty and enormous range: She could go from demure repression to uninhibited outbursts of raw emotion, sometimes within the same performance. Yearning showcases her most astonishing metamorphosis as Reiko, a war widow who has spent two decades dutifully serving her late husband’s family. She insists that she is content with her meager life—cooped up in a small grocery store that is now being squeezed out by a modern supermarket—but she is shaken up by a declaration of love from her handsome young brother-in-law Koji (Yuzo Kayama), and eventually decides to return to her distant hometown. She embarks on a train, and he pursues her; thus begins the most sublime of Naruse’s transformative journeys. Every frame is suddenly charged with beauty and the uneasy, thrumming possibility of change and renewal. As the silvery train slices through misty landscapes and grimy cities, a series of mostly wordless scenes traces the shift in Reiko’s feelings for Koji, leading up to a quietly piercing epiphany as she finally faces her pent-up loneliness and desire.

Yearning (Mikio Naruse, 1964).

The film’s original title, Midareru, does not mean “yearning.” Its meanings include: to fall into disorder, become disheveled, be disturbed or mixed-up. When applied to flowering trees, it means “to bloom in profusion.” All of these apply to Naruse’s women and their stories. At the end of Yearning, Takamine confronts the tragic outcome of her own confusion in a close-up that is among the greatest in cinema. Her features scarcely change, but behind her eyes she seems to pass through every stage of grief in a rapid, noiseless collapse, leaving a black hole that sucks all feeling into it. The world may betray Naruse’s characters, but they also betray themselves.

The perfection of this moment, in one of the last films of Naruse’s long career, emerges from his acceptance of life’s insoluble messiness. Like the hardworking heroine of Untamed, who curtly dismisses an ikebana (flower arranging) teacher, saying, “I don’t have time for this,” his films resist pretty images and find beauty in women’s weed-like resilience, growing in neglected places on the cloudiest days.

![“[You] Build a Movie Like You Build a Fire”: Lost Highway DP Peter Deming on Restorations, Lighting and Working with David Lynch](https://filmmakermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/1152_image_03-628x348.jpg)

![Dan Gilroy Talks ‘Andor,’ Tyranny, Writing Mon Mothma’s Fiery Speeches, Bix’s Great Sacrifice & More [The Rogue Ones Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/13114943/Dan-Gilroy-Andor-Interview.jpg)

![Ice Cube Says TSA Took His iPad—It’s Back Now, But He’s Not Letting It Go [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/ChatGPT-Image-Jun-14-2025-06_37_14-AM.jpg?#)

![Juicy rumors, but how far will cardholders be squeezed? [Week in Review]](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Juicy-rumors.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Problem Framing: Rewire How You Think, Create, and Lead with Rory Sutherland](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/rort-sutherland-35.png)