Cannes 2025 | National Security Threats

Illustration by Franz Lang.I never expected my first dispatch from the 78th Cannes Film Festival to begin with a message shared on Truth Social. Deranged as it sounds, though, Trump’s promise to impose one-hundred percent tariffs on foreign film productions has hovered ominously over the Croisette.“The Movie Industry in America is DYING a very fast death,” President Trump ranted on May 5 (caps his), pointing his finger at the incentives other countries are offering US filmmakers to draw them away from Hollywood’s hallowed grounds. “This is a concerted effort by other Nations,” apparently, “and therefore, a National Security threat.” Perhaps the edition’s more muted atmosphere can be chalked up to this economic volatility. “Where did the hype go?” Variety quotes an anonymous streaming-service executive as wondering early into the fest. Indeed, studios seem less inclined than usual to splash out money on advertising; no equivalent of the two-story recreation of an Air Force pilot helmet paid for by Paramount to salute the premiere of Top Gun: Maverick in 2022 was erected to welcome this year’s Tom Cruise vehicle, Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning. Asked ahead of the film’s Cannes bow if the franchise capstone—shot in different locations around the world—would fall under the new levy scheme, Cruise replied, “We’d rather answer questions about the movie.” Vague as it was, the answer was at least in keeping with the “cinema for cinema’s sake” stance that the festival tends to parrot. Cannes’s ostrich-like tendency to ignore some of our most urgent humanitarian crises is nothing really novel; just last year, artistic director Thierry Frémaux went as far as to suggest the event should not concern itself with what he shrugged off as “polemics”: “The main interest for all of us remains the cinema.” What is new, per The Hollywood Reporter, is that on top of the standard protocol all festival staffers need to comply with, Cannes has issued internal guidelines requesting its employees to maintain “political neutrality” as they engage with guests and social media. The resulting cognitive dissonance (the world’s on fire; let’s pretend it isn’t) turned the opening ceremony into a surreal affair. As labor activists from the festival workers collective Sous les écrans la dèche (“Under the screens, the waste”) mounted protests over working conditions, Robert De Niro turned his Honorary Palme d’Or acceptance speech into a chance to rally the audience against “America’s Philistine president,” urge everyone to protest and vote, and finally offer his two cents on Trump’s new threats. “You can’t put a price on creativity,” the actor quipped, “but you can put a tariff on it.” So far, so Cannes. But if the US President’s tirade feels of a piece with the cultural entrenchment his administration has long championed, the idea that foreign productions should amount to a national security threat isn’t just outright ridiculous. It’s also hopelessly out of touch with the way the industry actually functions. Many contemporary titles are the result of coproductions pulling in resources from different countries (Cannes itself, with its gigantic Marché du Film stretching across the ground floor of the Palais du Festival, has served as a vital incubator for many such joint efforts). Coincidentally, one of the best official competition entries, a film I haven’t stopped thinking about since it premiered on day two, was one such example: Óliver Laxe’s Sirât (all titles 2025 unless otherwise noted). Sirât (Óliver Laxe, 2025).A Spanish-French coproduction, Laxe’s fourth feature is the third he’s set in Morocco. In his early twenties, the Parisian-born Spaniard moved to Tangiers to set up a filmmaking workshop for impoverished kids, an experience that inspired his debut, You Are All Captains (2010), in which he cast himself as a director who moved to the city to make a film with underprivileged children and then watched as the project took all sorts of unexpected turns. His follow-up, Mimosas (2016), weaves together two stories, ostensibly set in different timelines, into an increasingly hallucinatory journey across Morocco’s arid outback. Which is one way of thinking about Sirât. Written by Laxe and Santiago Fillol—who’s coauthored all of Laxe’s features—the film centers on Luis (Sergi López), a single father who roams Morocco in search of his missing daughter with his young son, Esteban (Bruno Núñez Arjona). It’s not that the girl was kidnapped, strictly speaking, as the boy confesses halfway through: “She’s an adult, and one day she just left.” What she did over the five months she spent away from home is anyone’s guess, though Luis reckons she spent them raving it up in one of those illegal Burning Man–style desert concerts with which Sirât opens. But no sooner does the man start sharing her pictures with some drugged-up dancers than the army arrives to shut down the party and escort all Europeans to the nearest airport. A war’s just brok

Illustration by Franz Lang.

I never expected my first dispatch from the 78th Cannes Film Festival to begin with a message shared on Truth Social. Deranged as it sounds, though, Trump’s promise to impose one-hundred percent tariffs on foreign film productions has hovered ominously over the Croisette.“The Movie Industry in America is DYING a very fast death,” President Trump ranted on May 5 (caps his), pointing his finger at the incentives other countries are offering US filmmakers to draw them away from Hollywood’s hallowed grounds. “This is a concerted effort by other Nations,” apparently, “and therefore, a National Security threat.”

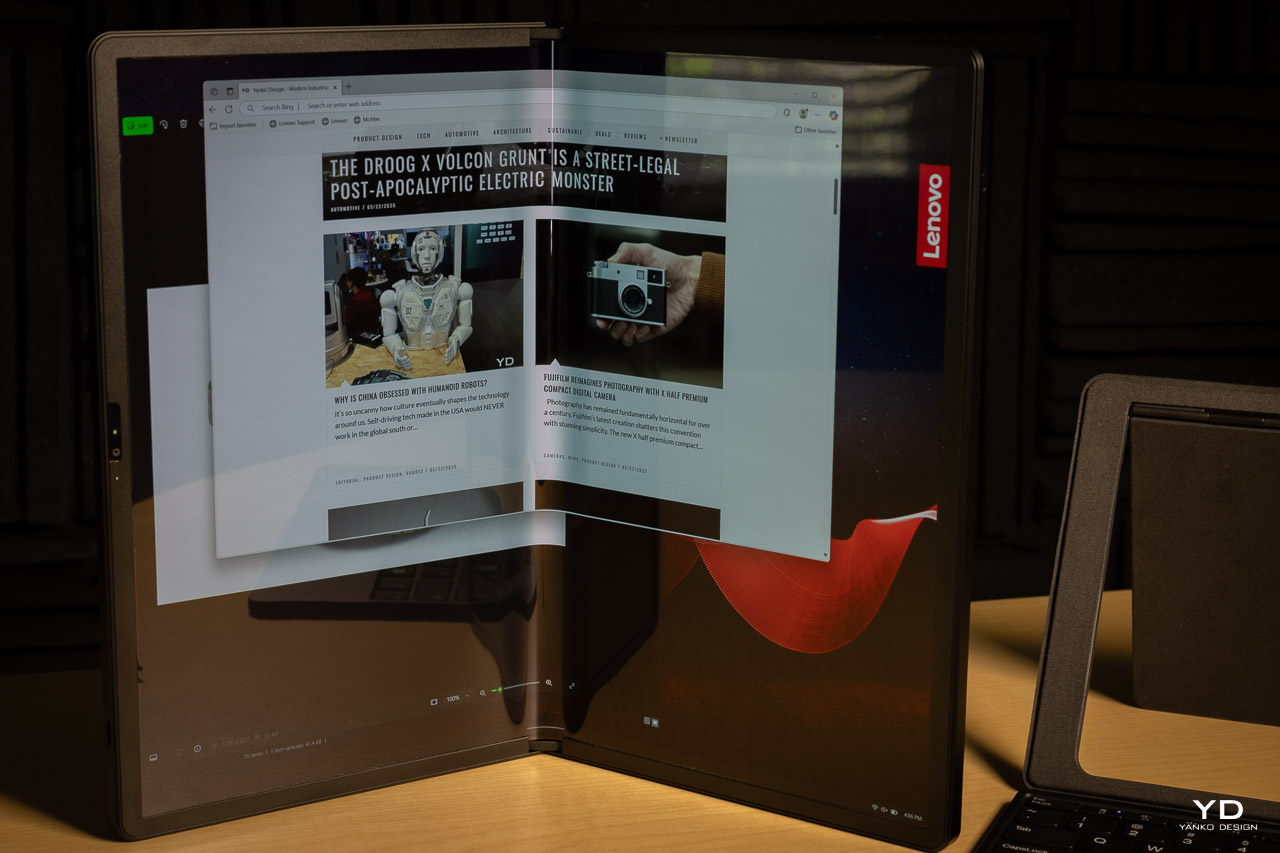

Perhaps the edition’s more muted atmosphere can be chalked up to this economic volatility. “Where did the hype go?” Variety quotes an anonymous streaming-service executive as wondering early into the fest. Indeed, studios seem less inclined than usual to splash out money on advertising; no equivalent of the two-story recreation of an Air Force pilot helmet paid for by Paramount to salute the premiere of Top Gun: Maverick in 2022 was erected to welcome this year’s Tom Cruise vehicle, Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning. Asked ahead of the film’s Cannes bow if the franchise capstone—shot in different locations around the world—would fall under the new levy scheme, Cruise replied, “We’d rather answer questions about the movie.” Vague as it was, the answer was at least in keeping with the “cinema for cinema’s sake” stance that the festival tends to parrot. Cannes’s ostrich-like tendency to ignore some of our most urgent humanitarian crises is nothing really novel; just last year, artistic director Thierry Frémaux went as far as to suggest the event should not concern itself with what he shrugged off as “polemics”: “The main interest for all of us remains the cinema.” What is new, per The Hollywood Reporter, is that on top of the standard protocol all festival staffers need to comply with, Cannes has issued internal guidelines requesting its employees to maintain “political neutrality” as they engage with guests and social media.

The resulting cognitive dissonance (the world’s on fire; let’s pretend it isn’t) turned the opening ceremony into a surreal affair. As labor activists from the festival workers collective Sous les écrans la dèche (“Under the screens, the waste”) mounted protests over working conditions, Robert De Niro turned his Honorary Palme d’Or acceptance speech into a chance to rally the audience against “America’s Philistine president,” urge everyone to protest and vote, and finally offer his two cents on Trump’s new threats. “You can’t put a price on creativity,” the actor quipped, “but you can put a tariff on it.”

So far, so Cannes. But if the US President’s tirade feels of a piece with the cultural entrenchment his administration has long championed, the idea that foreign productions should amount to a national security threat isn’t just outright ridiculous. It’s also hopelessly out of touch with the way the industry actually functions. Many contemporary titles are the result of coproductions pulling in resources from different countries (Cannes itself, with its gigantic Marché du Film stretching across the ground floor of the Palais du Festival, has served as a vital incubator for many such joint efforts). Coincidentally, one of the best official competition entries, a film I haven’t stopped thinking about since it premiered on day two, was one such example: Óliver Laxe’s Sirât (all titles 2025 unless otherwise noted).

Sirât (Óliver Laxe, 2025).

A Spanish-French coproduction, Laxe’s fourth feature is the third he’s set in Morocco. In his early twenties, the Parisian-born Spaniard moved to Tangiers to set up a filmmaking workshop for impoverished kids, an experience that inspired his debut, You Are All Captains (2010), in which he cast himself as a director who moved to the city to make a film with underprivileged children and then watched as the project took all sorts of unexpected turns. His follow-up, Mimosas (2016), weaves together two stories, ostensibly set in different timelines, into an increasingly hallucinatory journey across Morocco’s arid outback. Which is one way of thinking about Sirât. Written by Laxe and Santiago Fillol—who’s coauthored all of Laxe’s features—the film centers on Luis (Sergi López), a single father who roams Morocco in search of his missing daughter with his young son, Esteban (Bruno Núñez Arjona). It’s not that the girl was kidnapped, strictly speaking, as the boy confesses halfway through: “She’s an adult, and one day she just left.” What she did over the five months she spent away from home is anyone’s guess, though Luis reckons she spent them raving it up in one of those illegal Burning Man–style desert concerts with which Sirât opens. But no sooner does the man start sharing her pictures with some drugged-up dancers than the army arrives to shut down the party and escort all Europeans to the nearest airport. A war’s just broken out, and vague as the film may be about its origins and location, its scale is large enough as to turn the country into a kind of Mad Max wasteland, leaving people to compete for gas and food. Undeterred, Luis dogs a small gang of partygoers deeper into the desert, Esteban in tow, hoping to find his daughter at the next rave—wherever that may be.

Each film Laxe has shot in Morocco has sent him further afield from Tangiers, and Sirât feels the least anchored to the city, unfurling as it does against vast wastelands captured by the director’s longtime cinematographer, Mauro Herce, as a series of increasingly haunting vistas. It’s a choice that affords Sirât the feeling of being unmoored from a sense of place (for all intents and purposes, this could be any desert) and also suits the polyglot cast: The unlikely “family” of ravers dad and son join speaks a mix of French, Spanish, and Moroccan Arabic. This type of dislocation isn’t new in Laxe’s cinema. In Mimosas, the desert already functioned as a kind of magical no-man’s-land, not a place so much as a portal to a realm where different stories could coalesce. Just as crucially, Sirât furthers Laxe’s interest in mining spirituality from that unforgiving landscape. Mimosas was split into three chapters named after distinct aspects of the Islamic liturgy, featuring among its characters a mechanic-cum-preacher. There are no prophets to be found this time—the kind of rootlessness that binds Luis to his fellow expats here accrues a more terrifying quality. The film’s mysticism instead emerges from Laxe’s astonishing alchemy of sounds and images. If God manifests anywhere in Sirât, it’s in the communion between Herce’s sun-scorched visuals and the bass-heavy techno tracks that accompany them throughout. At its most hypnotic (a descriptor Sirât earns from its opening sequence, with Herce’s camera moving between intoxicated dancers, lost to everything but the music), Laxe’s latest reminded me of Ben Russell’s psychedelic ethnographies, Trypps (2005–10). As in that series—and in the seventh, desert-set installment especially—there’s a sense throughout Sirât that Laxe isn’t just chronicling a trip (both senses of the word apply), but trying to make cinema produce its own experience: to make it a site of transcendence itself.

In Muslim eschatology, sirat denotes the bridge each person must traverse on their way to paradise; only the righteous succeed, with the rest succumbing to a flaming hell. How Sirât lives up to that prophecy is something that’s best kept secret; this is that rare film that leaves one absolutely clueless as to where it will go. Suffice to say that, past a tragic pivot, the film’s grammar changes, with Cristóbal Fernández’s editing relying on dissolves to heighten the characters’ growing disassociation with the real world and evoke a sort of mirage. On my way to Cannes, I wondered—as I have since 2022—if anything this year would rival the breathtaking experience of Albert Serra’s Pacifiction, another title that landed in the official competition as a kind of space oddity: a film that didn’t seem beholden to an industrial or festival aesthetic but represented an electric encounter with the screen. Three years later, Cannes may have finally granted us a worthy heir.

Nouvelle Vague (Richard Linklater, 2025).

I kept thinking about Sirât almost as often as I thought about Trump’s threats, largely because of how Laxe’s spellbinding film seemed to refute the President’s myopic understanding of the medium. which seem to miss one of cinema’s salient traits: its porosity. Cinema is, by definition, a porous art form; every film exists in conversation with those that came before it, and each cinematic wave that’s ever swept through history has made its way to directors far away from its geographic epicenter. Few titles this year spoke to that permeability more eloquently than Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague, “the story of Godard making Breathless,” per its lapidary logline, “told in the style and spirit in which Godard made Breathless.” I must confess I was a little skeptical of what seemed to amount to—and in some ways is—an exercise in nostalgia. But Linklater’s approach is not museological. Even as Nouvelle Vague is so fastidiously concerned with recreating both the world Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) ambled through (shot in Paris, the film relies on extensive visual effects to conjure the city circa 1959) and the very textures of Godard’s first masterpiece (1.37:1 aspect ratio, black-and-white palette, scratchy sound design…), Linklater doesn’t plunge the movement and its members in formaldehyde, but gives their tempestuous creative struggles an infectious energy. Like so many of its French New Wave predecessors, Nouvelle Vague is basically a hangout movie, and there was something oddly fitting about watching the Cahiers du Cinéma gang kvetch about the festival’s narrow-minded approach to art in a theater named after Cahiers cofounder and critic André Bazin, just a stone’s throw away from the tiny venue on Rue d’Antibes where Breathless premiered in 1960 (the film did not officially screen as part of the festival, and was shortly thereafter deemed immoral and banned for viewers under eighteen). As Linklater’s cast graced the screen looking uncannily like the cinema titans they’d been summoned to play (Roberto Rossellini, Éric Rohmer, Agnès Varda, Raoul Coutard…), chuckles began to echo all around me, and I joined in, equal parts delighted to see those ghosts brought back to life and worried about how many other than the cinephiles around me would find their impersonations as amusing. Is Nouvelle Vague best appreciated by those already well-versed in the film at its center and the people who made it?

Hardly. Its synopsis notwithstanding, one doesn’t need an encyclopedic knowledge of the French New Wave, Breathless, and its iconoclastic auteur to bask in the youthful let’s-just-go-out-and-make-it energy that Linklater conjures. And while Nouvelle Vague carries little of Godard’s own revolutionary spirit (are we really going to fault it for that?), there’s an earnestness to the way its director revisits some of his heroes that harks back to Me and Orson Welles (2008). We watch Godard as he fritters time away, delays production, and refuses to commit to a script (much less write one), all while Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) and Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) wonder if the film will ever be released—or finished. Not unlike Godard himself, Linklater has long stress-tested cinema’s limits, from the daisy-chain tapestry of Slacker (1990), to the temporal sprawl of Boyhood (2014), to Waking Life’s (2001) animated dreamscapes. Nouvelle Vague shows none of these films’ experimentalism, but the pleasures it offers are no less gratifying. Beholden as it is to its immortal touchstone, the film gradually seems to transcend it to tell of something much more universal. That’s because Linklater isn’t after authenticity for authenticity’s sake. For all his fanatical attention to detail and faithfulness to Breathless’s style, the director leaves his performers ample room to breathe life into these characters and steer Nouvelle Vague away from a mere recreation of its ur-text and its authors. Throughout, there’s a sense of a filmmaker watching with wide-eyed wonder as a gaggle of reckless youngsters set out to do what they love, and in the process change the medium forever. This unbridled affection doesn’t just make Nouvelle Vague a heartfelt, rousing tribute to the act of creation. It also manifests itself in the way Linklater humanizes Godard—he’s not an august master to be revered, but an anxious, rebellious rule-breaker. The film, in faithful Godardian fashion, teems with all sorts of memorable quotes, the line I’ve gone back to most often is one Godard utters early on, fretting over the premiere of his friend and Cahiers colleague Truffaut’s feature debut, The 400 Blows (1959). “It’s too late,” he mutters, “I’m the last of the Cahiers directors to make a feature.” He was 29 then; like very few other visionaries, he’d stay young forever, a walking embodiment of an Edgar Lee Masters verse: “Genius is wisdom and youth.”

The Phoenician Scheme (Wes Anderson, 2025).

Linklater was not the only American filmmaker in competition to shoot beyond his native turf. Ever since The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), Cannes regular Wes Anderson has relied on Berlin’s Studio Babelsberg as production partner, and his latest, The Phoenician Scheme, is his fifth shot almost in its entirety on its iconic lots (the oldest large-scale film studio in the world, Babelsberg opened in 1912, producing, among others, landmarks like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis [1927]). But to fuss over the exact filming locations of Anderson’s projects is beside the point. The Phoenician Scheme takes place in another world of Anderson’s making, joining fictional settings like Zubrowka (The Grand Budapest Hotel), Ennui-sur-Blasé (The French Dispatch, 2021), and the fictional desert town after which Asteroid City (2023) was named. The titular Phoenicia is a supposedly profitable, “dormant” region modeled off the Arabian peninsula, which tycoon Anatole “Zsa-zsa” Korda (Benicio del Toro) wants to explore and exploit. This fictitious geography is in keeping with the director’s trademark mise-en-scène. Like its predecessors, The Phoenician Scheme unfolds inside meticulously designed soundstages, photographed in 35mm (this time not by regular cinematographer Robert D. Yeoman but Bruno Delbonnel) with a multi-plane depth that lets you bask in the frame’s symmetries, rhyming colors, and props. We’ve been here before, and I suspect this familiarity accounts for why debates around Anderson’s output by now feel as predictable as his detractors would have you believe his films are. But to chastise these films for looking the same is to miss the specificities of each imaginary world, including the way each speaks to our troubled present.

The ensemble cast is once again massive—so large that a bus was hired to shuttle the cast to the red carpet—and the story itself has an emotional core that treads territory similar to the director’s earlier projects. Anderson has never shied away from self-anthologizing, and the fraught family unit at The Phoenician Scheme’s center—a widowed father (Rushmore, 1998) trying to win over his estranged loved ones (The Royal Tenenbaums, 2001)—is a foundational motif. Chased by a gang of entrepreneurs determined to cripple his financial empire (and kill him, if need be), Zsa-zsa reunites with his 21-year-old daughter, nun Liesl (Mia Threapleton), to make her the sole heir of his empire—on a “trial basis”—and derail his rivals’ plans. But the kind of infrastructure he wants to build in Phoenicia requires exorbitant amounts of cash. Unfazed by the many attempts on his life, he enlists his daughter and a Norwegian professor (Michael Cera) he’s hired to teach him all about entomology on a journey to secure funds from former business partners.

I wouldn’t go as far as to peg Del Toro’s character as an avatar of the current US President—in an illuminating pre-premiere interview with Bilge Ebiri at Vulture, Anderson himself dismissed the suggestion, citing instead shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, Italian film producer Carlo Ponti, and the Ottoman British fixer Calouste Gulbenkian, credited as the first middleman to help the West exploit the oil riches of the Middle East. But for a story that pivots on a megalomaniac eager to fiddle with the truth and backstab relatives and associates alike, The Phoenician Scheme feels attuned to our zeitgeist, not least for its somber atmosphere. “Nihilistic” isn’t a descriptor I ever thought I’d associate with Anderson’s universe. But his latest—haunted as it is by death and interspersed with black-and-white sequences staging Zsa Zsa’s final judgment before God (Bill Murray, who else?)—may be darker than anything else in his filmography, as evinced in part by Alexandre Desplat’s score, no longer joyful but oddly mournful. Even Liesl, in the end, experiences her own crisis of faith. “When I pray,” she tells her father, “no one answers.” To criticize Anderson for the film’s airless quality, as some have done, is to play into the director’s hands: All his works rest on a tension between their painstakingly designed worlds and the way their denizens’ lives inevitably unravel. Which is to say the bleakness running through The Phoenician Scheme speaks to present-day anxieties, in sync with the mood of our times.

Sound of Falling (Mascha Schilinski, 2025).

One of the strongest films I’ve seen at the festival so far, shot as it was in and around an old farm in Northern Germany, spoke a language that simultaneously captured the details of its setting while transcending the confines of a single, claustrophobic location. Like her debut feature, Dark Blue Girl (2017), Mascha Schilinski’s official competition entry, Sound of Falling, is a cross-generational study of life inside one house, not unconcerned with the unearthed memories of its tenants so much as with evoking what it feels like to dredge them out of the mind. Spanning a century, the film follows four girls from distinct decades: young child Alma (Hanna Heckt) in pre-WWI Germany, teenage Erika (Lea Drinda) in the 1940s, Angelika (Lena Urzendowsky) living under the German Democratic Republic, and finally Lenka (Laeni Geiseler) in the present day. But Sound of Falling doesn’t proceed chronologically, nor does it feel exclusively tethered to the quartet’s perspectives. Its trajectory is circuitous; photographed by Fabian Gamper (who also lensed Dark Blue Girl) and edited by Evelyn Rack, the film moves balletically across its different eras, which are joined by long Steadicam sequences that function like passageways through time. A shot may begin by trailing after Alma, only for Gamper’s camera to sneak out of one room to chase the kid into another—catapulting us several years into the future, all in the same uninterrupted take. Sound plays a key role in this narrative flow, with designers Billie Mind and Jürgen Schulz sourcing non-diegetic noises like the distant howling of the wind or the faint scratching of a vinyl record to create bridges between storylines and epochs. In another filmmaker’s hands, such precious choreographies might register as excessively showy; in Schilinksi’s, they approximate something entrancing: a kind of séance.

I don’t use that word lightly. A work haunted by the past and committed to bringing its spectral accumulations into conversation with the present, Sound of Falling unfurls as a kind of ghost story. Death is omnipresent, and insofar as Schilinski filters domestic barbarities (intramural violence, suicides, incest) through the perspective of children witnessing them, the overall journey might bear a passing resemblance to Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon (2009). But the tone is less funereal than mysterious. Primed as I’ve been since January to see David Lynch’s fingerprints everywhere I look, there’s a couple of shots featuring kids and insects crawling into their open mouths that seem modeled on this particularly disturbing moment from Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). Though perhaps the filmmaker with whom Schilinski’s vision feels most aligned is Terence Davies, whose autobiographical “resurrections” of life in postwar Liverpool similarly dance across time, free from the obligations of linear chronology or plot. Sound of Falling might well be in dialogue with all those influences, and I’m sure new connections will crop up on further viewings. More importantly, Schilinki’s second feature offers something that’s become increasingly rare across the festival circuit: the electrifying feeling of watching a bold new voice come into their own. This is the sort of work an event like Cannes should champion—a film that testifies that cinema, for all our concerns over its moribund shape and the new threats the industry will have to confront, is still an indispensable means of making sense of the world and our place in it.

Continue reading our coverage of Cannes 2025.

![Kick Your Way Out of Hell in ‘Kick’n Hell’ on July 21 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/kicknhell.jpg)

![Love and Politics [THE RUSSIA HOUSE & HAVANA]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/therussiahouse-big-300x239.jpg)

![The Screed We Need [FAHRENHEIT 9/11]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/fahrenheit_9-11_collage.jpg)

![‘The Studio’: Co-Creator Alex Gregory Talks Hollywood Satire, Seth Rogen’s Pratfalls, Scorsese’s Secret Comedy Genius, & More [Bingeworthy Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22130104/The_Studio_Photo_010705.jpg)

![‘Romeria’ Review: Carla Simón’s Poetic Portrait Of A Family Trying To Forget [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22133432/Romeria2.jpg)

![‘Resurrection’ Review: Bi Gan’s Sci-Fi Epic Is A Wondrous & Expansive Dream Of Pure Cinema [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22162152/KUANG-YE-SHI-DAI-BI-Gan-Resurrection.jpg)

.jpg?#)

.png?#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)