Cannes Review: The History of Sound is a Tenderly Felt Drama with Terence Davies-Style Musicality

It’s strange to hear backwood Appalachian fiddle folk in a French theater at the hand of a South African director portraying the queer, song-collecting lives of two American men who are madly, delicately in love and played by British stars. Thanks to Paul Mescal, it’s also quite lovely. The History of Sound––Oliver Hermanus’ hushed ode […] The post Cannes Review: The History of Sound is a Tenderly Felt Drama with Terence Davies-Style Musicality first appeared on The Film Stage.

It’s strange to hear backwood Appalachian fiddle folk in a French theater at the hand of a South African director portraying the queer, song-collecting lives of two American men who are madly, delicately in love and played by British stars. Thanks to Paul Mescal, it’s also quite lovely.

The History of Sound––Oliver Hermanus’ hushed ode to New England’s rich tapestry of folk history, adapted by Ben Shattuck from his short-story collection of the same name––is a tenderly felt drama sung in whisper and sorrow, the kind that almost guarantees a cry for anyone weakened by a phenomenal homegrown voice or piercing romance. Its alternately hyper-specific and vast range of vocals, styles, and tunes suggest the minor dawning of a lesser-known American sound.

Much as Inside Llewyn Davis and O Brother, Where Art Thou? sought to reintroduce music the Coens trusted would resonate with modern audiences, The History of Sound means to show us the power of (primarily a cappella) folk songs of their time and place. T Bone Burnett will be proud.

Hermanus’ approach culls from the familiar emotional and tonal territory of Brokeback Mountain, a movie so influential it inspired a landslide of iterations that have nearly rendered Ang Lee’s singular approach normative over the two decades since it released. But The History of Sound manages to pull something fresh from the form. Where Lee captured a tiny (but indicative) rural portion of the closeted American West in the ’60s and ’70s, Hermanus sets his sights on New England near the end of and just after WWI.

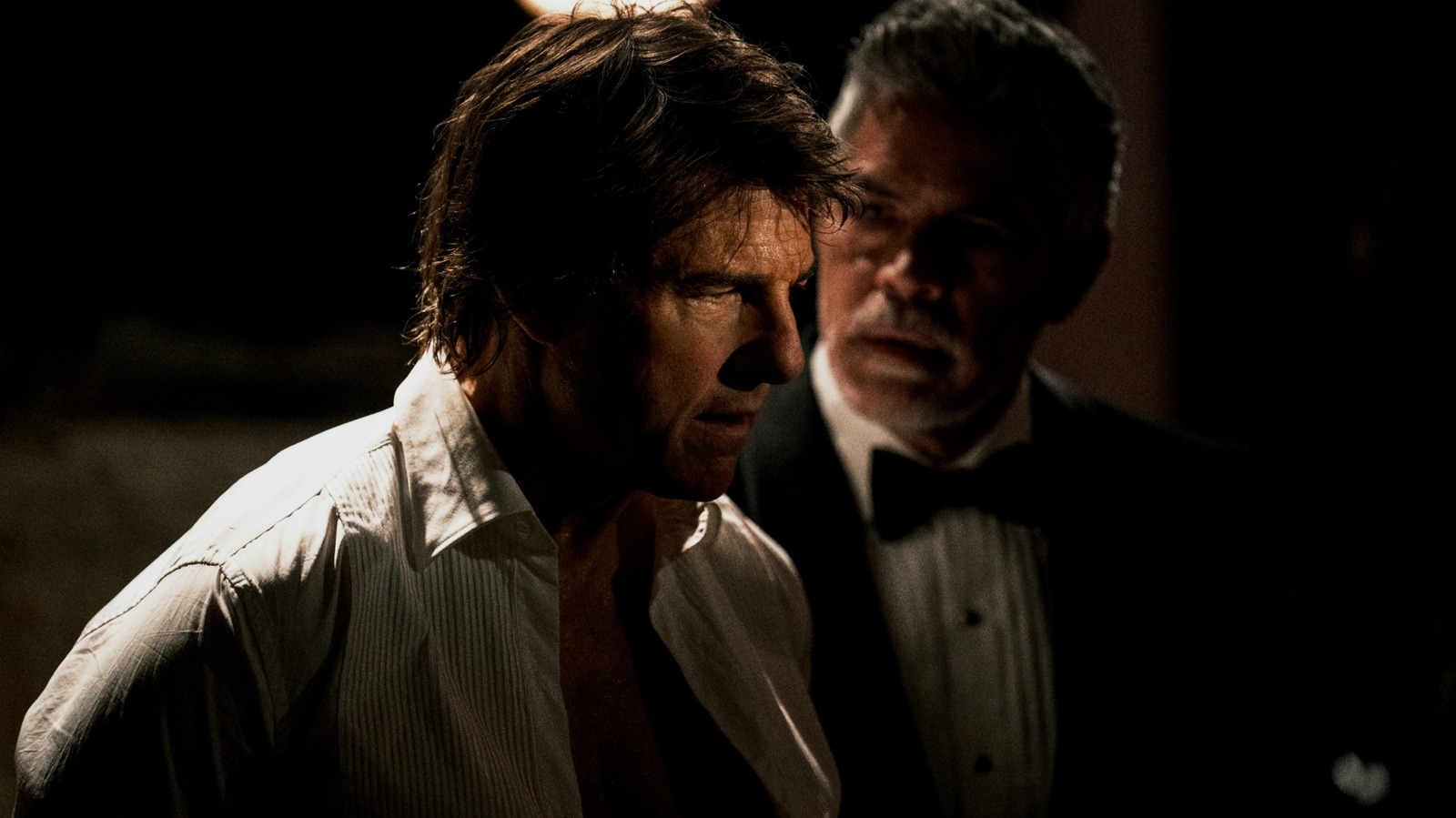

Lionel (Mescal) and David (Josh O’Connor) meet at Boston College in 1917 and fall fast in love, if you’re reading the signals. If you’re someone alive at the time, you’re probably not picking up on them. Self-assured and well-disguised in a gentleman’s behavior of the period, they just seem like best friends. Lionel is quiet and inexpressive, a blank smile plastered on his face. From the outside, it seems he could be hollow––until he sings. David, on the other hand, is a loose and lively fellow, so charming he could’ve been a grifter in another life. In this one, his passion fell to music.

Not long after they meet, David is drafted to the war and Lionel goes back home to take care of his adoring-but-stringent mother, whose life has never gone beyond the Massachusetts farm on which she raised her son. She’s appalled when, a year later, Lionel informs her he’ll be leaving to embark on an indefinite, song-collecting journey with his college buddy David, an expedition the latter’s university is funding for the department’s research.

It’s 1919, the war is finally over, spirits are high, and their reconnection is wriggling with potential. Using the Edison wax cylinder phonograph invented only 40 years prior, the two set out across the Northeast to record iterations and dialects of the region’s folk songs. All they have is camping gear, recording equipment, and each other. We so quickly glide through the trip––serene (and unfortunately sexless; the film is anything but carnal) and successful––that it’s over before we know it. The time spent listening to the compilation of gentle, soulful songs and strong voices whisps away in what feels like seconds, giving scenes a cherished quality. The downside of that brilliance is how long sequences after the trip, sans music, can feel. Not all song-less stretches play dull, but they tend to thrive more on the potential of a song emerging than a long dialogue taking shape. Lionel eventually begins a posh life abroad as a singer, where he meets a woman that he appears to genuinely fall in love with for a short time. Or at least tries to fall in love with. In a gay romance film, however, that’s obviously doomed.

I don’t know if The History of Sound is worth revisiting for its devastating romance, the likes of which deepen this story’s emotion but make it a much heavier haul, but I’m counting down the days until I can revisit its songs, sonically and visually; the hearing speaks for itself. But there’s something about being in the room with them up-close while they’re singing that brings the world to a halt, something about the songs that lift your soul with their peculiar melancholic power.

The oft-occurring tavern- or kitchen-set song is reminiscent of Terence Davies and his spotlighting of the old-world way people casually sang in homes and public forums to enjoy themselves, or communally mourn, or any reason in-between that justified the sweet sound of music. Before music was infinitely accessible and explorable at the flick of a finger, it was a more precious thing. Hearing a new type of song, voice, or instrument could be an otherworldly experience.

That’s still true today, of course, but it has to catch us in the right moment. We hear, know about, and often turn off all kinds of music; or at least we can if we want to. They couldn’t. The recording of sound, much less music that could be replayed, caused even greater excitement. On their journey from Massachusetts to Maine––a particularly special landing place for the Lewis and Clark of the Northeasternmost dialects of American folk––the reactions of those they pitch on the project are fascinating. The possibility of this technology is more like wizardry to people of that time, who approach the phonograph and recording sessions with caution.

As in Davies’ films, the sudden, plentiful a cappella folk songs disarm any listener of their modern context to help understand why the experience was so powerful. In this sense, Mescal is perfectly cast. His singing voice is a sacrosanct soft-boy croon equal-parts pretty, sturdy, and true (one can’t help but think about the years Mescal spent with Phoebe Bridgers). It’s a relief to see him out of the blockbuster machine that doesn’t know how to wield his subtlety, even better to find him back in the kind of emotionally dense film in which he can triumph. He and O’Connor both wear the century-old look well.

If no other reason compels, see The History of Sound for its songbook. Traditional pieces like “Silver Dagger,” made mildly popular by Joan Baez in 1960, are so well-arranged and distilled that they have the potential to be sleeper sad-indie hits of the year.

The History of Sound premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival and will be released by MUBI.

The post Cannes Review: The History of Sound is a Tenderly Felt Drama with Terence Davies-Style Musicality first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Kick Your Way Out of Hell in ‘Kick’n Hell’ on July 21 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/kicknhell.jpg)

![Love and Politics [THE RUSSIA HOUSE & HAVANA]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/therussiahouse-big-300x239.jpg)

![The Screed We Need [FAHRENHEIT 9/11]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/fahrenheit_9-11_collage.jpg)

![‘The Studio’: Co-Creator Alex Gregory Talks Hollywood Satire, Seth Rogen’s Pratfalls, Scorsese’s Secret Comedy Genius, & More [Bingeworthy Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22130104/The_Studio_Photo_010705.jpg)

![‘Romeria’ Review: Carla Simón’s Poetic Portrait Of A Family Trying To Forget [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22133432/Romeria2.jpg)

![‘Resurrection’ Review: Bi Gan’s Sci-Fi Epic Is A Wondrous & Expansive Dream Of Pure Cinema [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22162152/KUANG-YE-SHI-DAI-BI-Gan-Resurrection.jpg)

.jpg?#)

.png?#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)