Cannes Review: Christian Petzold’s Mirrors No. 3 is an Enigmatic Drama About Letting Go

Christian Petzold’s fifteenth feature Mirrors No. 3 marks his fourth with Paula Beer, the actor-muse he first directed in 2018’s Transit, a film that shares significant themes with his newest––chiefly that of total strangers inexplicably recognizing each other and immediately feeling a deep, soulful bond with nary a word. Needless to say Mirrors No. 3 […] The post Cannes Review: Christian Petzold’s Mirrors No. 3 is an Enigmatic Drama About Letting Go first appeared on The Film Stage.

Christian Petzold’s fifteenth feature Mirrors No. 3 marks his fourth with Paula Beer, the actor-muse he first directed in 2018’s Transit, a film that shares significant themes with his newest––chiefly that of total strangers inexplicably recognizing each other and immediately feeling a deep, soulful bond with nary a word. Needless to say Mirrors No. 3 is, like the others, an enigma.

We open on Laura (Beer) looking longingly over a small rural bridge, staring at the running river water below as if to silently wish tragedy upon herself. She walks down to the water. A harbinger in an all-black zentai suit slowly standup-paddleboards past her, the soundscape grazed by the soft noise of tumbling water around the ore. They stare at each other as he glides by. Then we stare at the water until her boyfriend corrals her back to the car. They’re in the middle of a road trip.

Suddenly we’re ripping down the street in a convertible with Laura, her boyfriend, and two haughty unknowns, the latter three of which won’t get more than a couple minutes’ screentime. They zip past Betty (Barbara Auer), a woman painting her fence, and Petzold briefly slows things to the microsecond in which Betty and Laura lock eyes and feel the mystifying bond that drives this story.

Coming from the third movement of French composer Maurice Ravel’s five-part piano suite, which Laura plays in the final act––a callback to Petzold’s Phoenix, which ends with a music moment so chilling the pianist is compelled to stop playing––Mirrors No. 3 is a strange title. It’s not difficult to make the connection to mirrors as a motif. But why such a seemingly insignificant tie proved strong and indicative enough for this honor remains buried somewhere within Petzold’s dense thematic logic, itself disguised by the movie’s simplicity in story and technique.

The four arrive at a marina to board a boat, but Laura pulls out in depression, much to her boyfriend’s frustration. On his way to drop her off at the nearest train station, they almost crash into Betty. Crisis averted, they peel off, only to total the car seconds later. The boyfriend dies, but Laura hardly has a scratch on her body––one of many mysteries looming under this story’s surface and never to be explored, intended to tease interest, created to be let go of.

That’s one of Petzold’s trademark moves: little mysteries that enrich, complicate, and abandon the story, filled out just too little to decipher, their ghost left behind to taunt the viewer with loose connections and peculiar feelings. On paper they simply suggest plot holes, but under the direction of Petzold’s unique pace, mood, and tone, those mysteries have become the glitter and glue of his filmography––what makes each film stand out, stick together, and stay in your mind. Unsurprisingly, Mirrors No. 3 is as committed to the idea as ever. Inch by inch, the concept of letting go emerges as the core theme.

Unbeknownst to herself, Laura wants to recover at Betty’s countryside home, and Betty excitedly allows it, offering round-the-clock care despite Laura hardly needing it. Laura is a piano student in Berlin, a classically trained musician and music-theory whiz able to play impressionist masterpieces at the drop of a hat or name the key of any song in seconds. Betty’s vocation is less clear. She’s a single woman taking care of her home but seems more like a mother, caring for Laura in the aftermath of the accident, telling Tom Sawyer tales before bed, and lovingly inviting her to live there post-recovery.

Still, there’s a lack of life to Betty’s house outside the fresh new coat on the outdoor fence, a visual foreshadowing of Laura’s presence in her life. Betty’s exotic herb garden is dying, her demeanor is timid, and her mounting love for life with Laura gives an overeager edge. Yet, in the light of Betty, the trauma of Laura’s wreck and her boyfriend’s death evaporates into thin air, as if it had never happened. As far as we can tell, it’s what Laura wanted.

That only covers the first ten minutes or so, but, per its meandering mysteries, Mirrors No. 3 is the kind of work best-served with as little information as possible. It’s not among Petzold’s greatest, but films like Barbara and Undine have made that a very high bar to clear. It’s textbook Petzold, which I mean as a major compliment. Don’t expect all of the mysteries to be uncovered. There is no big explainer moment or narratively satisfying closure, the likes of which Petzold rejects, but the enigmas that do reveal themselves yield rare treasures.

Mirrors No. 3 premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival and will be released by Metrograph Pictures.

The post Cannes Review: Christian Petzold’s Mirrors No. 3 is an Enigmatic Drama About Letting Go first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Kick Your Way Out of Hell in ‘Kick’n Hell’ on July 21 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/kicknhell.jpg)

![Love and Politics [THE RUSSIA HOUSE & HAVANA]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/therussiahouse-big-300x239.jpg)

![The Screed We Need [FAHRENHEIT 9/11]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/fahrenheit_9-11_collage.jpg)

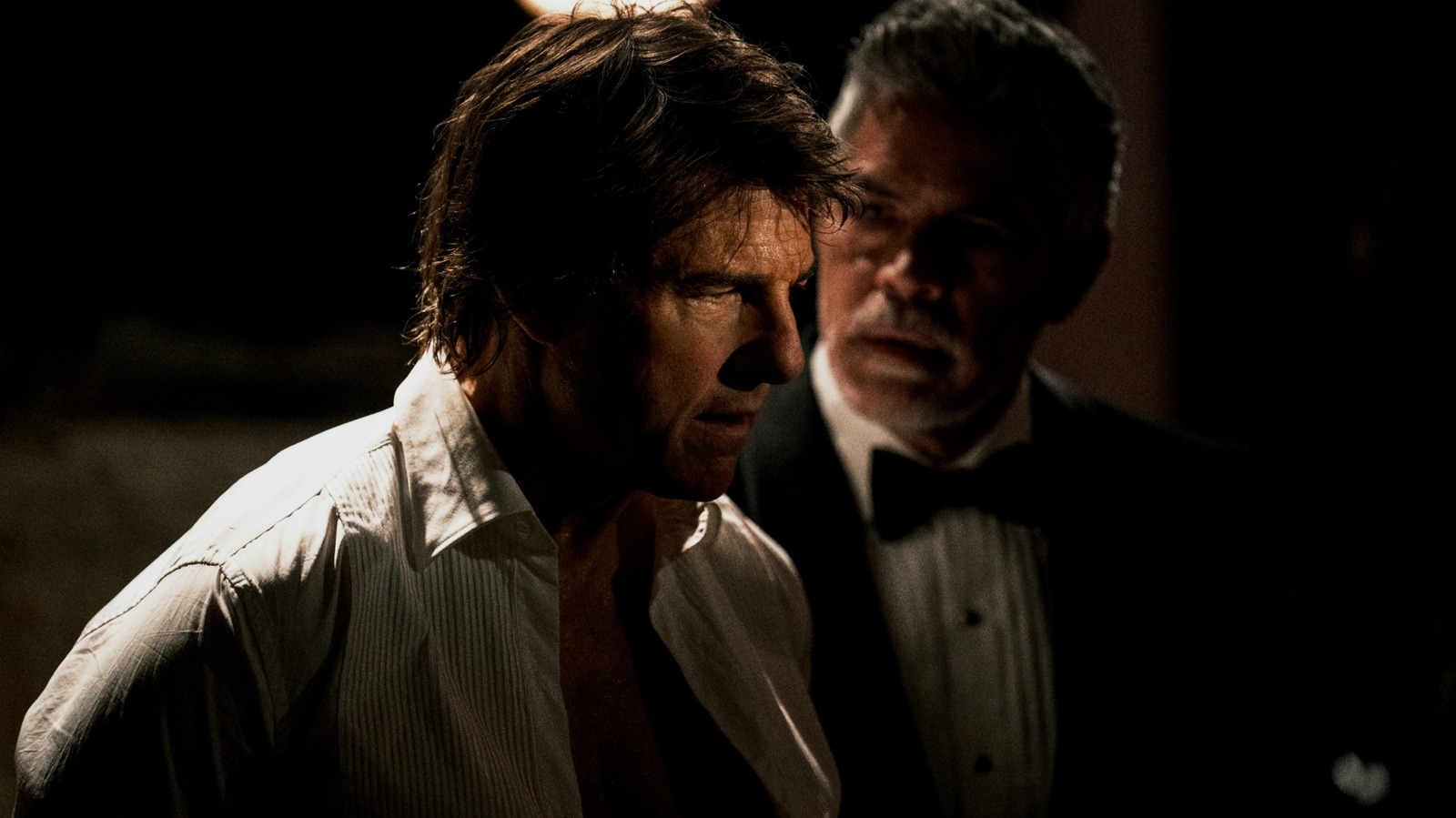

![‘The Studio’: Co-Creator Alex Gregory Talks Hollywood Satire, Seth Rogen’s Pratfalls, Scorsese’s Secret Comedy Genius, & More [Bingeworthy Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22130104/The_Studio_Photo_010705.jpg)

![‘Romeria’ Review: Carla Simón’s Poetic Portrait Of A Family Trying To Forget [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22133432/Romeria2.jpg)

![‘Resurrection’ Review: Bi Gan’s Sci-Fi Epic Is A Wondrous & Expansive Dream Of Pure Cinema [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22162152/KUANG-YE-SHI-DAI-BI-Gan-Resurrection.jpg)

.jpg?#)

.png?#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)