Cannes Review: The Phoenician Scheme Finds Wes Anderson Losing the Plot in Breakneck, Tiresome Spy Comedy

We begin with music that’s uncharacteristically tense for a Wes Anderson film––chugging cellos leading a full orchestra that’s more Mission: Impossible than Moonrise Kingdom––and opener à la Nolan blockbusters: an assassination attempt. It’s an exhilarating launch into a story that starts petering out soon after. Renowned criminal mastermind Zsa Zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro) sits […] The post Cannes Review: The Phoenician Scheme Finds Wes Anderson Losing the Plot in Breakneck, Tiresome Spy Comedy first appeared on The Film Stage.

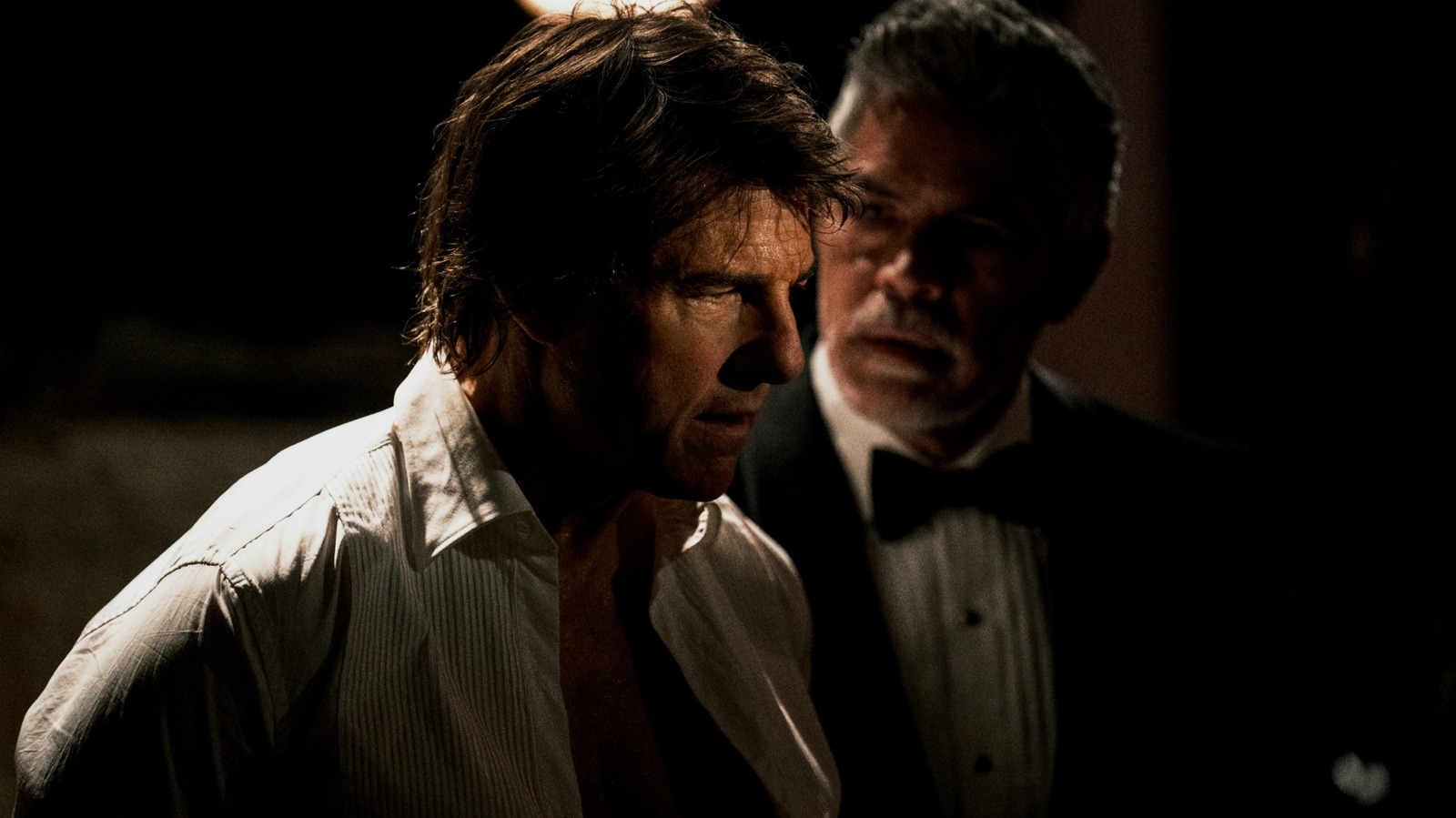

We begin with music that’s uncharacteristically tense for a Wes Anderson film––chugging cellos leading a full orchestra that’s more Mission: Impossible than Moonrise Kingdom––and opener à la Nolan blockbusters: an assassination attempt. It’s an exhilarating launch into a story that starts petering out soon after. Renowned criminal mastermind Zsa Zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro) sits before a gorgeously designed train car much like the off-white, wooden, burgundy, and plaid train car that will take him and his associates around Phoenicia for the rest of the movie. An unfortunate associate is crammed into the back corner. Without warning, a bomb obliterates any semblance of said corner, and we launch into The Phoenician Scheme, never to take a breath.

Zsa Zsa is a downright horrible man, as blunt about his actions as critics would be, but lacking any awareness to realize what makes them wrong. He’s the kind of guy who genuinely asks, “Why would anybody do something I didn’t tell them to do?” He bribes, launders, racketeers, swindles banks, starts wars, evades taxes, and lives in the Italian Palazzo whose cold, variegated marbled interiors lend Scheme much of its icy mood.

It’s been six years since Zsa Zsa has seen his daughter Liesl (newcomer Mia Threapleton), but a near-death experience has convinced him to call her back from nunhood and make her sole heir to his estate should one of the many assassination attempts on his life succeed. That he has nine (biological) sons is neither here nor there, but they do provide some delightful moments. As do the adopted ones. (Since Rushmore, Anderson has been great at getting comedic performances out of kids.)

The nefarious lead keeps getting in airplane crashes––this is his sixth, and not his final in the film––and almost dying because every government, intelligence agency, and person in power is trying to kill him. Being nationless and wholly unaccountable to any laws, it’s the only way to stop him from his global domination of infinite illicit pursuits. Anderson explains as much in a furious blizzard of exacting details, side- and back-story forays, and design-laden flourishes, the likes of which have defined his storytelling since The Royal Tenenbaums. As always, he gets his point across about characters and tone, but where it’s made his films better in the past, here the pace is so breakneck that it dilutes.

We could talk about the wife-murdering subplot, the “no slavery, no famine, no dormitories” subplot, the hand grenade buffoonery, or Wes Anderson’s weird version of a basketball game. There’s Bryan Cranston and Tom Hanks, but all of them hold little substance and pale in comparison to the main narrative thrust: filling the gap. Zsa Zsa, with Liesl and insect tutor Bjorn (a wonderful Michael Cera) in tow, is dead set on finding the last bit of funding to complete the (almost) newly minted Trans-mountain Locomotive Tunnel project, where both ends of the track come comically short of meeting in the middle.

The fundraising should go smoothly. It’s a manageable amount to raise and Zsa Zsa has his people and proposed frontages of the final bill. But the helplessly depraved father keeps trying to swindle his business partners and they catch him every time, the funding for the last piece of track quickly slipping from Zsa Zsa’s grasp again and again. Broken into five fundraising chapters (represented by shoeboxes harboring Zsa Zsa’s plan for each) The Phoenician Scheme concerns visits with wily characters like Marseille Bob (Mathieu Amalric), Prince Farouk (Riz Ahmed), and Uncle Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch) the crew of tag-alongs growing larger with each chapter.

For the first time, Wes Anderson has overindulged his taste for quirk. The Phoenician Scheme is too formulaic for its own good, lost in the haze of mathematically zany dialogue, structure, story, and design that becomes tiresome to pay attention to, much less keep up with. It’s often pleasant, pretty, impressive, and well-scored (and we’ll note the spectacle of design shortly), but that isn’t enough for someone of his caliber. Where is the emotion? The feeling? The Owen Wilson perspective of his storytelling soul?

In The Royal Tenenbaums‘ Criterion commentary, Anderson notes that his films up to that point (Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, Tenenbaums) amount to a meeting between his and Owen Wilson’s perspectives. Tenenbaums ended up being the last movie he wrote with the star, whose roles got smaller and smaller amidst gigantic casts. Now it’s easier to tell what was Anderson and what was Wilson, and in particular what the director carried from his collaborator. Anderson’s last few works seem to be losing touch with the humanity that Wilson brought to a spectacularly artistic mind: a penchant for craft and design have eclipsed his attention to relatable, emotional detail in story and character to the point he’s gone full gallery mode.

Watching The Phoenician Scheme is like walking through an immaculately curated home-design or vintage store, oohing and aahing at all the remarkable things you’d never seen or previously imagined. It’s fun, interesting, relatively shallow, inspiring in certain crafts, and usually becomes a sluggish experience after sorting through everything for a while. If you’re not buying something, the perusing itself isn’t the kind of experience you take home with you. Or if you do take back something non-material, it’s the abstract memory of eccentric patterns, wallpapers, weapons, costumes, tchotchkes, pieces of furniture––tabled ideas for your next room remodel or dishware set.

But instead of a store, we’re in a Synecdoche, New York-sized factory. And instead of walking, we’re sprinting. The production design, set decoration, costuming, makeup, art, props, locations, et al. are characteristically fantastic; they may even have reached their peak. But with age, Anderson seems to be losing his patience for the appreciation of it all, giving us little time to acknowledge, much less admire, the details.

The meager presence of A-list side players suggests one of his humblest casts in years, a notion the celebrity-adorned poster implies otherwise. Most scenes comprise del Toro, Threapleton, and Cera, with side roles ranging from a handful of scenes to a cameo for everyone else listed out.

One of its brighter moments––a hilariously irrational pilot and first-assistant exchange mid-plane-crash––will add jet fuel to the fire of conversation surrounding season two of The Rehearsal as it continues to air. Shockingly, an action scene stands as one of Scheme‘s most inspired moments, begging the question: what type of movie should Wes Anderson make next if his art-project films are finally losing their luster?

The veteran writer-director has some new tricks up his sleeve, one in particular that calls on Bergman-esque black-and-white cinematography and afterlife motifs. Whenever Zsa Zsa teases death again, Anderson lifts us to the heavens with him, first flashing a horror-tinged negative of the image before glitching the real one into its place in a blinding angelic sheen of light, only to discover God and his jurors (let the casting surprise you) in judgment mode.

The neutral feast for the eyes that is the already familiar bathroom image is an inspired take on the master shot, whose form is rarely iterated on. But the tricks don’t amount to more than brief pleasantries that vanish within seconds among the sandstorm of narrative details which follow. Here’s hoping for a Wes of more depth next round.

The Phoenician Scheme premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival and opens on May 30 from Focus Features.

The post Cannes Review: The Phoenician Scheme Finds Wes Anderson Losing the Plot in Breakneck, Tiresome Spy Comedy first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Kick Your Way Out of Hell in ‘Kick’n Hell’ on July 21 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/kicknhell.jpg)

![Love and Politics [THE RUSSIA HOUSE & HAVANA]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/therussiahouse-big-300x239.jpg)

![The Screed We Need [FAHRENHEIT 9/11]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/fahrenheit_9-11_collage.jpg)

![‘The Studio’: Co-Creator Alex Gregory Talks Hollywood Satire, Seth Rogen’s Pratfalls, Scorsese’s Secret Comedy Genius, & More [Bingeworthy Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22130104/The_Studio_Photo_010705.jpg)

![‘Romeria’ Review: Carla Simón’s Poetic Portrait Of A Family Trying To Forget [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22133432/Romeria2.jpg)

![‘Resurrection’ Review: Bi Gan’s Sci-Fi Epic Is A Wondrous & Expansive Dream Of Pure Cinema [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22162152/KUANG-YE-SHI-DAI-BI-Gan-Resurrection.jpg)

.jpg?#)

.png?#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)