Urgency and ambition in Cannes Acid 2025

There are hidden gems ripe for discovery in the youngest and smallest Cannes sidebar. The post Urgency and ambition in Cannes Acid 2025 appeared first on Little White Lies.

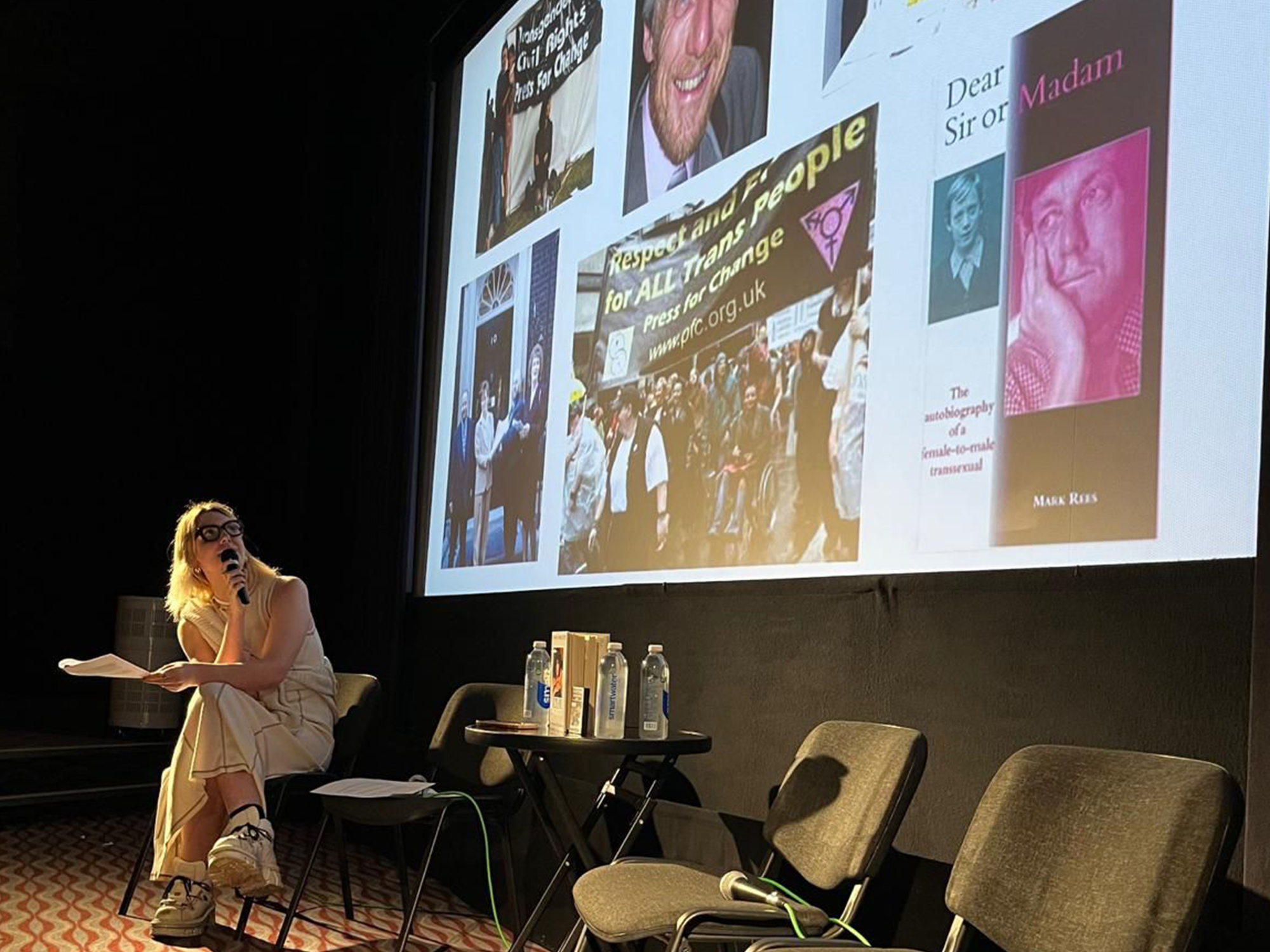

On April 15 of this year, ACID, the youngest and smallest of the parallel selections at Cannes, announced its lineup, which included Sepideh Farsi’s Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, a portrait of the 25-year-old Palestinian photographer Fatima Hassouna and her work documenting the ongoing atrocities in her native Gaza. The next day, Hassouna was killed, along with 10 members of her family, when an Israeli airstrike targeted her home. Both ACID and Cannes released statements in response to her death; the difference between the two is illuminating. Cannes said that Hassouna and her family “were killed by a missile that hit their home,” and numbered among “the far too many victims of the violence that has engulfed the region.

The Programme Committee of ACID 2025, meanwhile, said that “an Israeli missile had targeted her home, killing Fatem and several members of her family,” making her “one more death added to the list of targeted journalists and photojournalists in Gaza, and at the time of writing, to the daily litany of victims who die under bombs, out of hunger, and because of politics of genocide that must be stopped and for which the Israeli far-right government must be held responsible.”

Cannes is, for better or worse, one of the defining bodies of contemporary institutional film culture, and letting individual filmmakers make political statements while assiduously pretending not to know what they’re saying is about the best we can hope for from institutional film culture at the moment. ACID’s tickets are available for booking through the Cannes website, but it is very much its own thing, even if, by programming Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, it made Fatima Hassouna the festival’s business, and motivated Palme d’or jury president Juliette Binoche to devote a couple minutes of her remarks at the opening ceremony to the martyred journalist.

Founded in the early 1990s, “L’Association du cinéma indépendant pour sa diffusion,” the independent film association for its distribution, supports independent film in France and internationally through a number of festival and theatrical exhibition initiatives. Its selection at Cannes every year is selected by a programming committee of association members, and its selection, this year as every year, reflects the affirmative priorities of the film artists who make up the association. This year, that seems to mean films whose politics are embodied in their urgency and ambition, as well as indie-universalist humanism from filmmakers from different backgrounds.

Another documentary, Sylvain George’s Obscure Night – “Ain’t I a Child,” registers among of the former category. George embeds with migrant boys in Paris as they hang out all at night in large throngs late night below the Eiffel Tower, sleeping rough, scavenging for coins and cigarette butts, comparing trajectories through Europe’s bureaucracies and custodial systems, plans for papers and arrest histories. Two and three quarter hours long and the culmination of a three-part series, the film uses duration, particularly within distended bull sessions and peacocking fights, similar to the earlier works of Pedro Costa, and the frames are classical as Costa’s are, too, but differently so: the film is in magazine-glossy black and white, full of striking angles on famous landmarks and unfamous, acne-scarred faces, both made equally heroic.

Like Lance Oppenheim, George finds revealing moments all the more striking for being conveyed in a conspicuously cinematic language of continuity editing and striking compositions. Given the film’s rapport with youth exploring an urban environment, comparisons could also be made to author-subject collaborative films like Bill and Turner Ross’ Tchoupitoulas or Michal Marczak’s All These Sleepless Nights, here achieved in the service of moving lives from the margins of Europe to the looming foreground.

Of the fiction films, the opening night selection, L’Aventura, is like Aftersun, seemingly inspired by autobiographical home movies of the filmmaker’s childhood family vacation. In Sophie Letourneur’s film, 11-year-old Claudine, her harried mother, her feckless stepfather, and her not-yet-potty-trained 3-year-old half-brother travel around Sardinia on their summer holidays. The film jumps back and forth, its chronology occasionally garbling as memory does, as the family re-narrates their trip as voice memos for Claudine’s cellphone. A rare acknowledgement of the lower-maintenance older sibling (but not so old that she’s forgotten the power of a sulk), these recaps, taking place at restaurants and recapitulating the bickering, lost wallets, missed turns, improvised itineraries, disappointing meals, gorgeous sunsets, and all-ages tantrums, are a classic memory-making exercise as well as a rare moment of calm in a family frazzled by meeting the very different demands of a tween and a toddler, and by the rivalries of a mixed family. Any film which features a 3-year-old boy in every scene is necessarily a documentary; Letourneur’s is relatably lively (if it’s not your family) and tense (if it is).

Drifting Laurent is a story of quarterlife male malaise, in which the eponymous failure to launch crashes for the offseason in a family friend’s empty ski condo in the foothills of a not-so-magic mountain. Then he stays, orbiting an inevitably quirky constellation of lost souls, among them a dying woman, hippie caretaker Béatrice Dalle, and her large adult son, a Viking reenactor and vlogger. The tone established by filmmakers Anton Balekdjian, Léo Couture and Mattéo Eustachon is tender, almost morose at times, but enlivened by comic moments of frankly confrontational social awkwardness, and a few gags dependent upon drolly specific camera positioning.

Another twentysomething malaise movie, Lauri-Matti Parppei’s debut A Light That Never Goes Out, is more pungent with textures of Braff. A classical flautist retreats to his childhood home in provincial Finland’s Rauma after a breakdown, and thaws under the watchful and antic ministrations of a manic pixie dream performance artist — a type that really does tend to thrive in the indulgent DIY culture of the Nordic welfare state. It helps that the director is also an experimental musician, and that the avant-punk band the wayward protagonist sort-of forms, which mixes ambient drone with d.i.y. effects like the sound of a hand mixer immersed in a gallon of water, is actually pretty good; also that the filmmaking is attentive to the subtleties of a novel location. (Attention to the masculine postures of the rougher urban areas outside of Lisbon is also the high point of Pedro Cabeleira’s Entroncamento, an overlong neon-night/interlocking character crime thriller that strikes its poses unconvincingly.)

One more young man in limbo is at the center of the best film I saw in ACID, and one of my highlights of the festival. A young student in New York City to catsit in a vacant apartment, sit idly at the front desk in a mostly empty art gallery, and cruise the mostly empty weeknight residential streets and dark park for sex is the subject of Drunken Noodles, from Lucio Castro. Castro’s End of the Century, a modular melodrama about boxes within boxes (apps on home screens of phones of people passing through Airbnbs and looking for sex on Grindr). His third film — the second, After This Death, just premiered at the Berlinale earlier this year to mixed reviews — follows End of the Century, one of the last great films of the 2010s, in taking abrupt leaps forwards and backwards in time, and maybe into and out of alternate realities, opening and foreclosing alternate human connections and life paths. Castro’s soothingly paced, exquisitely poised vision of queer life and city life defined by contingency and possibility is both radical and bittersweet.

The post Urgency and ambition in Cannes Acid 2025 appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Fascinating Rhythms [M]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/m-fingerprint.jpg)

![Love and Politics [THE RUSSIA HOUSE & HAVANA]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/therussiahouse-big-300x239.jpg)

![‘The Studio’: Co-Creator Alex Gregory Talks Hollywood Satire, Seth Rogen’s Pratfalls, Scorsese’s Secret Comedy Genius, & More [Bingeworthy Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22130104/The_Studio_Photo_010705.jpg)

![‘Romeria’ Review: Carla Simón’s Poetic Portrait Of A Family Trying To Forget [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22133432/Romeria2.jpg)

![‘Resurrection’ Review: Bi Gan’s Sci-Fi Epic Is A Wondrous & Expansive Dream Of Pure Cinema [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/22162152/KUANG-YE-SHI-DAI-BI-Gan-Resurrection.jpg)

![They Flew $19,000 Business Class—Here’s What I Think Denver Airport Execs Were Really Doing [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Denver_international_airport.jpg?#)

-1-52-screenshot.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)