Little Lambs, Big Back Story

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan Thuras: If you visit Colonial Williamsburg these days, you will find that there’s one burning question on everybody’s mind. Darin Durham: Everybody’s always worried about where Wilbur is. Anna Reinhardt: People will sometimes even email us and say like, “I saw you move Wilbur, where did Wilbur go?” Darin: We get text messages on a daily basis about the whereabouts of Wilbur. Dylan: Wilbur is a sheep, a very friendly sheep, and a little one too, just only a year old. Born last year during what’s called the lambing season. Lambing season happens every spring in Colonial Williamsburg and it’s a really big deal, mainly because these baby lambs are very small and very, very, very cute. Darin: Some people plan their trips to Williamsburg during lambing season for that purpose. This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Anna: I think the energy around lambing season is always really fun and the weather is nice and the flowers are blooming and the little lambs are running around, I mean … Darin: And jumping. They like to jump. Anna: Yeah, it’s really cute. Dylan: But in addition to being extremely small and extremely cute, these lambs tell a pretty incredible story about American history. It’s a story that involves sheep smuggling, extinction, and a president of the United States. I’m Dylan Thuras and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. This episode was produced in partnership with Visit Williamsburg. Dylan: And today we are going to Williamsburg to talk about a very special breed of sheep. One that was so prized, so incredibly valuable, that during the 18th century there was a lot of illicit, under-the-table sheep trading going on. And after some ups and downs, these valuable sheep actually went extinct in the United States before ultimately being brought back right here in colonial Williamsburg. Crazy sheep story. Darin Durham and Anna Reinhardt are both animal husbanders at Colonial Williamsburg. It means they spend a good part of each day chasing after sheep in historical costumes. And it is not every day you see someone join a Zoom meeting in a period outfit. Darin: Yes, I am dressed like a rural person in the 18th century right now. We were just shearing sheep at our farm site on the other end of town. Anna was also dressed up, but now she is back in her lovely Colonial Williamsburg sheep t-shirt. Anna: I was covered in sheep gunk. I was smelly. Yeah, so now I’m wearing a hot pink t-shirt with a cartoon sheep on it, and you can’t see on the video, it says Colonial Williamsburg. Dylan: Shearing a sheep is really hard work. I’ve tried to do this once, and it’s just incredibly difficult. First off, they weigh between 100 and 200 pounds, so they’re just difficult to wrangle. And also, they wiggle around. They’re kind of, you know, they get nervous and want to run away. But then there’s the fact that at Colonial Williamsburg, they’re not using modern electric clippers. They are shearing with actual shears, like scissors. Anna: I feel like I need to prepare by going home and just sitting on the couch and squeezing a tennis ball, because you’re opening and closing the shear so much that by the end of it, I find that my forearms are a little sore. Dylan: Using electric clippers would make this process go much faster. But that is just not the point. The Colonial Williamsburg experience is all about feeling like you’ve been dropped into the 18th century. So not only are Anna and Darin using old-fashioned shears, they’re also using them on old-fashioned sheep. Anna: One of the things that we try to do here is line up animals that reasonably could have been in our kind of region during the colonial time period. Darin: And the Leicester Longwool had a big part to play in a lot of that. Dylan: Yes, we are talking about a specific breed of sheep called the Leicester Longwool, which was like basically the first designer breed ever. They’re like the sheep version of the labradoodle. And it all started back in England in the 1740s. Darin Durham: The Leicester Longwool breed was developed by geneticists in England by the name of Robert Bakewell. I mean, he’s still in a lot of agricultural textbooks even today. And the Leicester Longwool breed itself is one of the first breeds of livestock that actually had a breed standard. So if you look at the American Kennel Club with all the dogs, it kind of started with the idea that Robert Bakewell came across with this particular breed of sheep. Dylan: Basically, Robert Bakewell wanted a sheep with a lot of meat on it and also a lot of wool. So he chose ewes and rams from his flock that were beefier or woolier, and then he bred them together. An

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan Thuras: If you visit Colonial Williamsburg these days, you will find that there’s one burning question on everybody’s mind.

Darin Durham: Everybody’s always worried about where Wilbur is.

Anna Reinhardt: People will sometimes even email us and say like, “I saw you move Wilbur, where did Wilbur go?”

Darin: We get text messages on a daily basis about the whereabouts of Wilbur.

Dylan: Wilbur is a sheep, a very friendly sheep, and a little one too, just only a year old. Born last year during what’s called the lambing season. Lambing season happens every spring in Colonial Williamsburg and it’s a really big deal, mainly because these baby lambs are very small and very, very, very cute.

Darin: Some people plan their trips to Williamsburg during lambing season for that purpose.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Anna: I think the energy around lambing season is always really fun and the weather is nice and the flowers are blooming and the little lambs are running around, I mean …

Darin: And jumping. They like to jump.

Anna: Yeah, it’s really cute.

Dylan: But in addition to being extremely small and extremely cute, these lambs tell a pretty incredible story about American history. It’s a story that involves sheep smuggling, extinction, and a president of the United States.

I’m Dylan Thuras and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. This episode was produced in partnership with Visit Williamsburg.

Dylan: And today we are going to Williamsburg to talk about a very special breed of sheep. One that was so prized, so incredibly valuable, that during the 18th century there was a lot of illicit, under-the-table sheep trading going on. And after some ups and downs, these valuable sheep actually went extinct in the United States before ultimately being brought back right here in colonial Williamsburg. Crazy sheep story. Darin Durham and Anna Reinhardt are both animal husbanders at Colonial Williamsburg. It means they spend a good part of each day chasing after sheep in historical costumes. And it is not every day you see someone join a Zoom meeting in a period outfit.

Darin: Yes, I am dressed like a rural person in the 18th century right now. We were just shearing sheep at our farm site on the other end of town. Anna was also dressed up, but now she is back in her lovely Colonial Williamsburg sheep t-shirt.

Anna: I was covered in sheep gunk. I was smelly. Yeah, so now I’m wearing a hot pink t-shirt with a cartoon sheep on it, and you can’t see on the video, it says Colonial Williamsburg.

Dylan: Shearing a sheep is really hard work. I’ve tried to do this once, and it’s just incredibly difficult. First off, they weigh between 100 and 200 pounds, so they’re just difficult to wrangle. And also, they wiggle around. They’re kind of, you know, they get nervous and want to run away. But then there’s the fact that at Colonial Williamsburg, they’re not using modern electric clippers. They are shearing with actual shears, like scissors.

Anna: I feel like I need to prepare by going home and just sitting on the couch and squeezing a tennis ball, because you’re opening and closing the shear so much that by the end of it, I find that my forearms are a little sore.

Dylan: Using electric clippers would make this process go much faster. But that is just not the point. The Colonial Williamsburg experience is all about feeling like you’ve been dropped into the 18th century. So not only are Anna and Darin using old-fashioned shears, they’re also using them on old-fashioned sheep.

Anna: One of the things that we try to do here is line up animals that reasonably could have been in our kind of region during the colonial time period.

Darin: And the Leicester Longwool had a big part to play in a lot of that.

Dylan: Yes, we are talking about a specific breed of sheep called the Leicester Longwool, which was like basically the first designer breed ever. They’re like the sheep version of the labradoodle. And it all started back in England in the 1740s.

Darin Durham: The Leicester Longwool breed was developed by geneticists in England by the name of Robert Bakewell. I mean, he’s still in a lot of agricultural textbooks even today. And the Leicester Longwool breed itself is one of the first breeds of livestock that actually had a breed standard. So if you look at the American Kennel Club with all the dogs, it kind of started with the idea that Robert Bakewell came across with this particular breed of sheep.

Dylan: Basically, Robert Bakewell wanted a sheep with a lot of meat on it and also a lot of wool. So he chose ewes and rams from his flock that were beefier or woolier, and then he bred them together. And ultimately, eventually, ta-da, you get this big, meaty, woolly sheep: the Leicester Longwool. Soon, the Leicester Longwools became famous for producing this super warm, super durable wool. It was the perfect wool for making blankets or coats. Now, during this period, the textile industry made up an enormous part of the British economy. And the British were very protective of their textiles. They passed all sorts of laws banning the colonies from producing their own wool and exporting it. Believe it or not, they also banned sheep like the Longwools from being sent out of Britain. These sheep were essentially a protected technology. Think of the CHIPS Act today. So, as you can imagine, people in the American colonies thought, “Oh, I really, really want to get my hands on these valuable sheep.”

Darin: And there were people, particularly rich planters, that were buying them off the black market. And there’s a pretty famous one. There’s this fellow on the Potomac River by the name of George Washington that bought some Leicesters off the black market.

Dylan: That’s right. George Washington was an illicit sheep trader.

Darin: Yeah, he called the black sheep market.

Dylan: There’s actually a letter from him where he’s complaining about all of these British statutes on sheep and then mentions that some, quote, “less scrupulous people have managed to get around them,” wink wink. He’s pretty careful to say that he didn’t do any of the importing directly, but it seems like he was definitely buying baby lambs from these smuggled sheep. All these British rules about sheep trading, they weren’t just annoying. They were exemplary of the fundamental problems between the colonies and the British. And so it became a political issue.

Anna: As we get closer to the American Revolution, a lot of farmers in Virginia get interested in the idea of trying to produce more wool as a form of economic independence and patriotism. People are saying, like, “Oh, yeah, it’s going to increase our economic independence.” And part of it is really political protest.

Darin: Washington has, what, between two and four hundred sheep at any given time.

Anna: Yeah, I think at one point he might have had close to 900. Not for long, though.

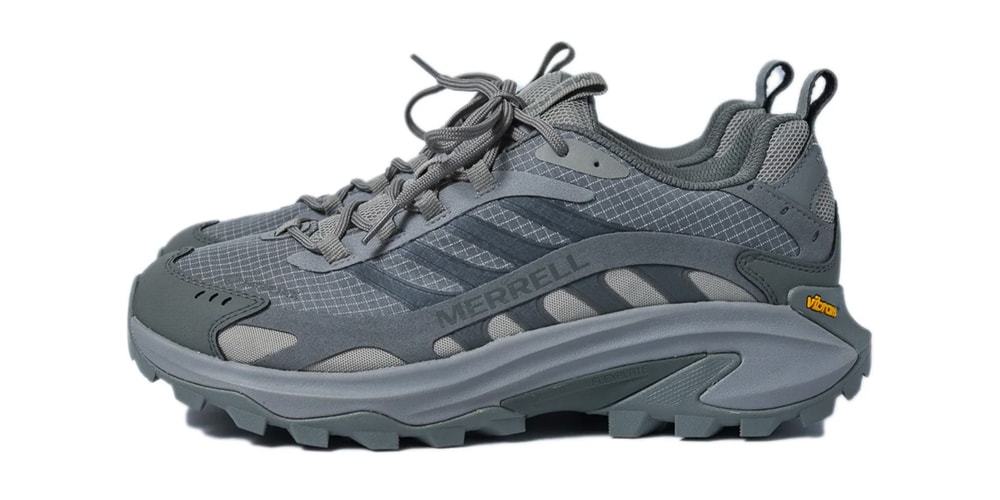

Dylan: For a long time, the Leicester Longwools were the gold standard of sheep. Everybody wanted one. The wool was strong and warm, had a kind of sheen to it even after you dyed it. But then a story that happens time and time again played out. A new kind of technology arrived on the block. A new breed of sheep from Spain. And actually, this one you’ve probably heard of. You probably even own a jacket or a sweater made from its wool. Merino sheep and Merino wool. The Merino sheep produced wool that was both softer and finer than the Leicester Longwool. So soft you could wear it right next to your skin. And soon, a kind of Merino mania began to spread. And the Leicester began to fall out of favor. By the 1940s, the Leicester Longwool was completely extinct in the United States.

Darin: And, you know, that’s kind of a problem because once you lose some of this genetic material, it’s gone forever. And there are hundreds of breeds of livestock that have actually become extinct. As young as this country is—you know, we’re going on 250 years—we’ve lost a lot of livestock that will never come back.

Dylan: Enter Colonial Williamsburg. In the mid-1980s, they started what was called their Rare Breeds Program. The goal was to bring back animals that had been really important to American life in the 18th century. Cows like the Milking Red Devon, or horses like the Cleveland Bay Horse. If you’ve ever seen the movie War Horse, that is a Cleveland Bay Horse. And to bring the Leicester Longwools back, Colonial Williamsburg had to track down a farmer in Australia that still had a flock.

Darin: Those Leicesters were brought over, flown over, and they had a flock here in Williamsburg, Virginia, and they had another satellite flock within about an hour and a half from here, and basically went from there. And now there’s, what, about 2,000 Leicesters registered at any given time now here in the United States?

Anna: The Livestock Conservancy tracks how rare different breeds are in North America. So there’s, just like an endangered species list, there’s extinct, there’s critically endangered, there’s threatened, and then there’s watch lists, and then you’re not on the list anymore. The Leicester Longwools have gone from extinct to, or functionally extinct at least, to threatened in North America, which is pretty good.

Darin: It’s probably our rare breeds program’s biggest success story, I would say.

Dylan: Today, Colonial Williamsburg is home to about 40 Leicester Longwool sheep, and more are born every year during lambing season, which, as we mentioned before, is unquestionably the cutest time of year to visit Colonial Williamsburg. And of course, back in the 1700s, the wool from these Leicester Longwools would have been made into fabric, and so that is what happens at Colonial Williamsburg, too. They shear the sheep once a year, spin it into yarn on an old-fashioned spinning wheel, and then weave it into fabric on these big looms. This fabric is usually made into rugs or horse blankets, used all around town. But if you have any crocheters or knitters in your life, they sometimes put up homemade yarn for sale in the gift shop.

Darin: And it’s a cool souvenir if you happen to come across it, because, you know, you’re in Colonial Williamsburg, that sheep was hand-shorn in an 18th century method. It’s an 18th century breed of sheep, and you’re getting a product that, I mean, wholeheartedly was, you know, started here and ended here, which is pretty neat.

Dylan: It’s like farm-to-table but for cloth, you know? Wool-to-yarn. Sheep-to-sweater. But even if you’re not in the market for yarn, you can still visit the sheep and the baby lambs, including Wilbur, and appreciate how they kind of set the vibe at the museum. You know that when you are walking around Colonial Williamsburg, you are seeing the things that people would have seen and hearing the things they would have heard, including all these cute little “bah” sounds.

Darin: You’re walking down the street at 7:30 in the morning, you hear roosters crowing, you hear cows mooing, you hear sheep bleating, and it really adds to the experience as a whole.

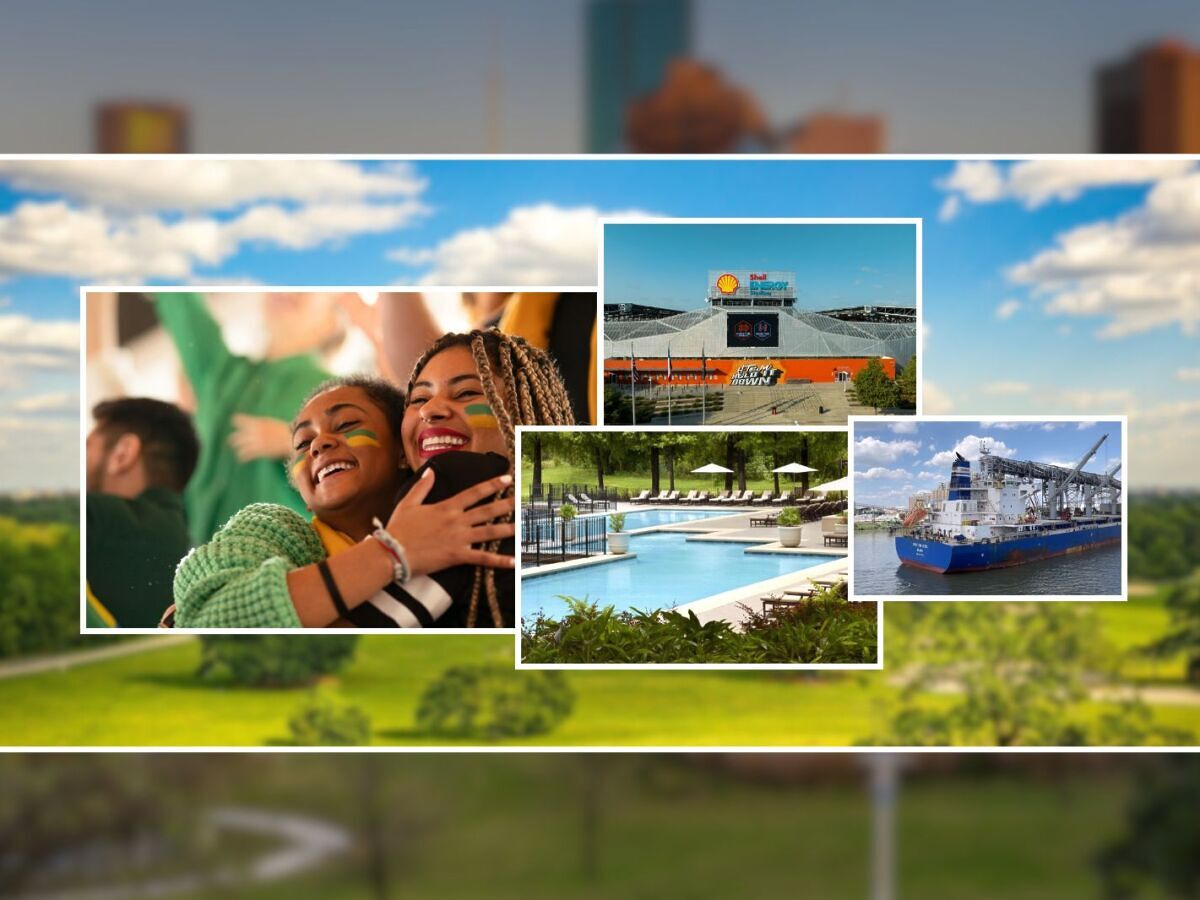

Dylan: You too can go and see these cute little baby lambs and visit the rare breeding program in Colonial Williamsburg. I personally find this to be one of the most interesting things about the whole experience. And while you’re there, you can explore more. You’re in this historic triangle where Williamsburg is one piece of it, but the whole region is this kind of intermix of nature and history. Nearby, you can go to Jamestown on the James River. You can see bald eagles and white deer and all of the wildlife that the English settlers would have seen when they arrived. Or you could go to Yorktown’s riverfront and see these battlefield landscapes and also understand this natural world that shaped colonial survival, whether it’s the Chesapeake Bay and its marine life or the wildlife in the forests that sustained soldiers during the American Revolution. You can find out all of this and more places to explore on Visit Williamsburg.

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

![Redrawing History [POCAHONTAS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/pocahontas-movie-poster.jpg)

![A Room With No View [ORPHANS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/orphans-poster.jpg)

![Familiarity Breeds Contempt [SCOOP]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/scoop-1.jpg)

![Steam Next Fest Demo for Dark Fantasy Dungeon Crawler ‘Horripilant’ Now Available [Trailer]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/horripilant.jpg?fit=900%2C580&ssl=1)

![Celebrity Guest [MISERY]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/misery.jpg)

![Not everything is user-friendly in this hobby – maybe we can help? [Week in Review]](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Copy-of-2025-Blank-Featured-Image-Template-970-x-485-px.png?#)

.jpg?updatedAt=1748848969283#)

.jpg)