“The Phones Became Weapons”: Anthony Dod Mantle on Animating 28 Years Later with Danny Boyle

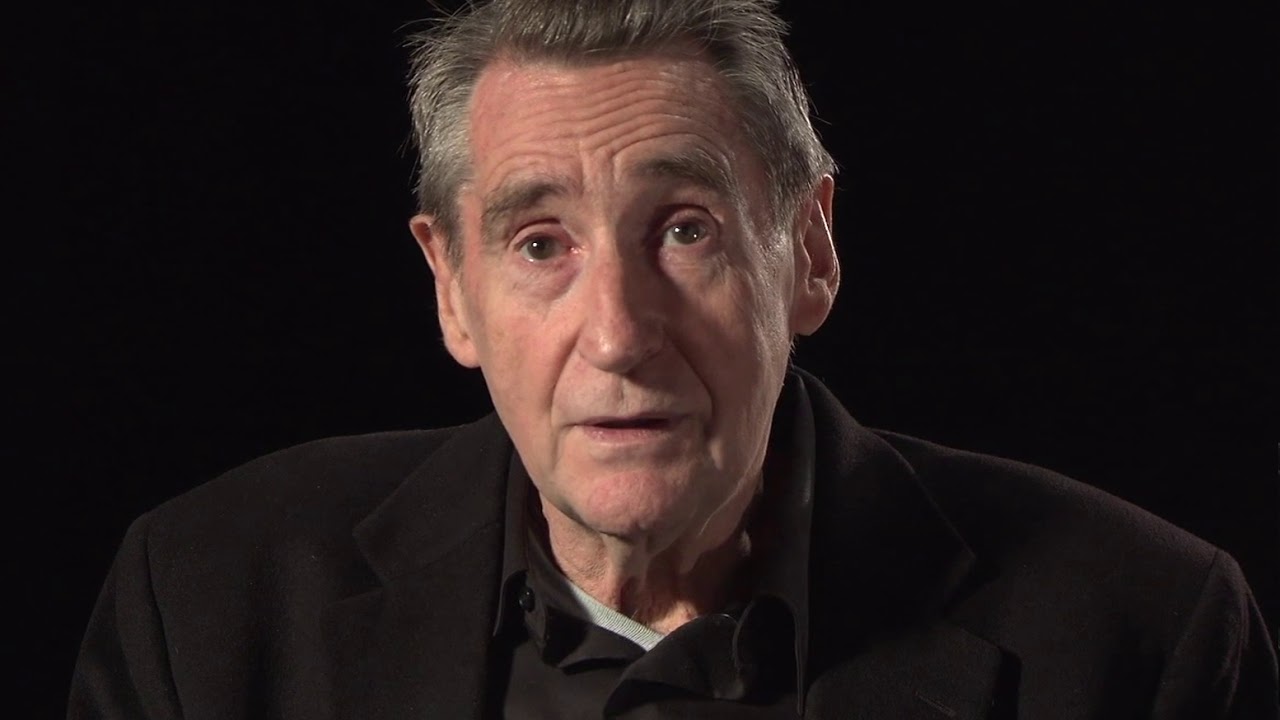

Anthony Dod Mantle has done more to advance digital photography than nearly any artist in any medium, a fact his humility rendered somewhat subtle during a career-spanning conversation I had the fortune of conducting in 2023. He could, nevertheless, casually mention that 28 Days Later constitutes “a historic film” without anyone batting an eye. The […] The post “The Phones Became Weapons”: Anthony Dod Mantle on Animating 28 Years Later with Danny Boyle first appeared on The Film Stage.

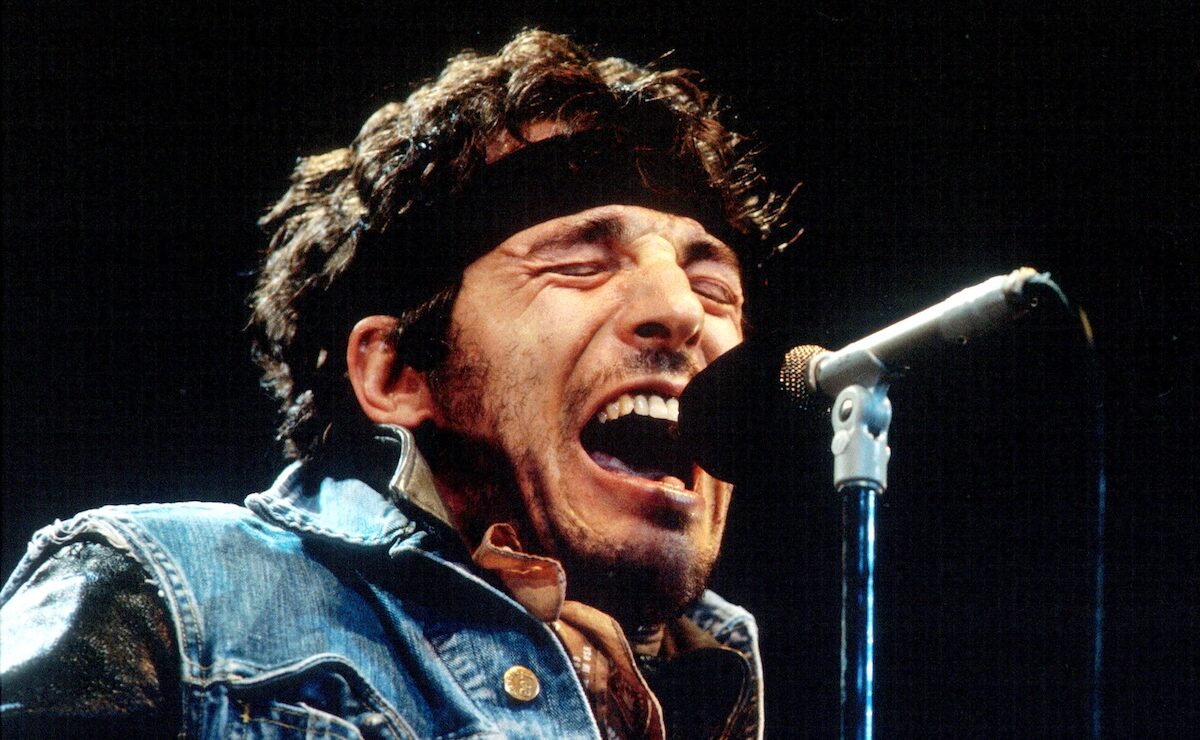

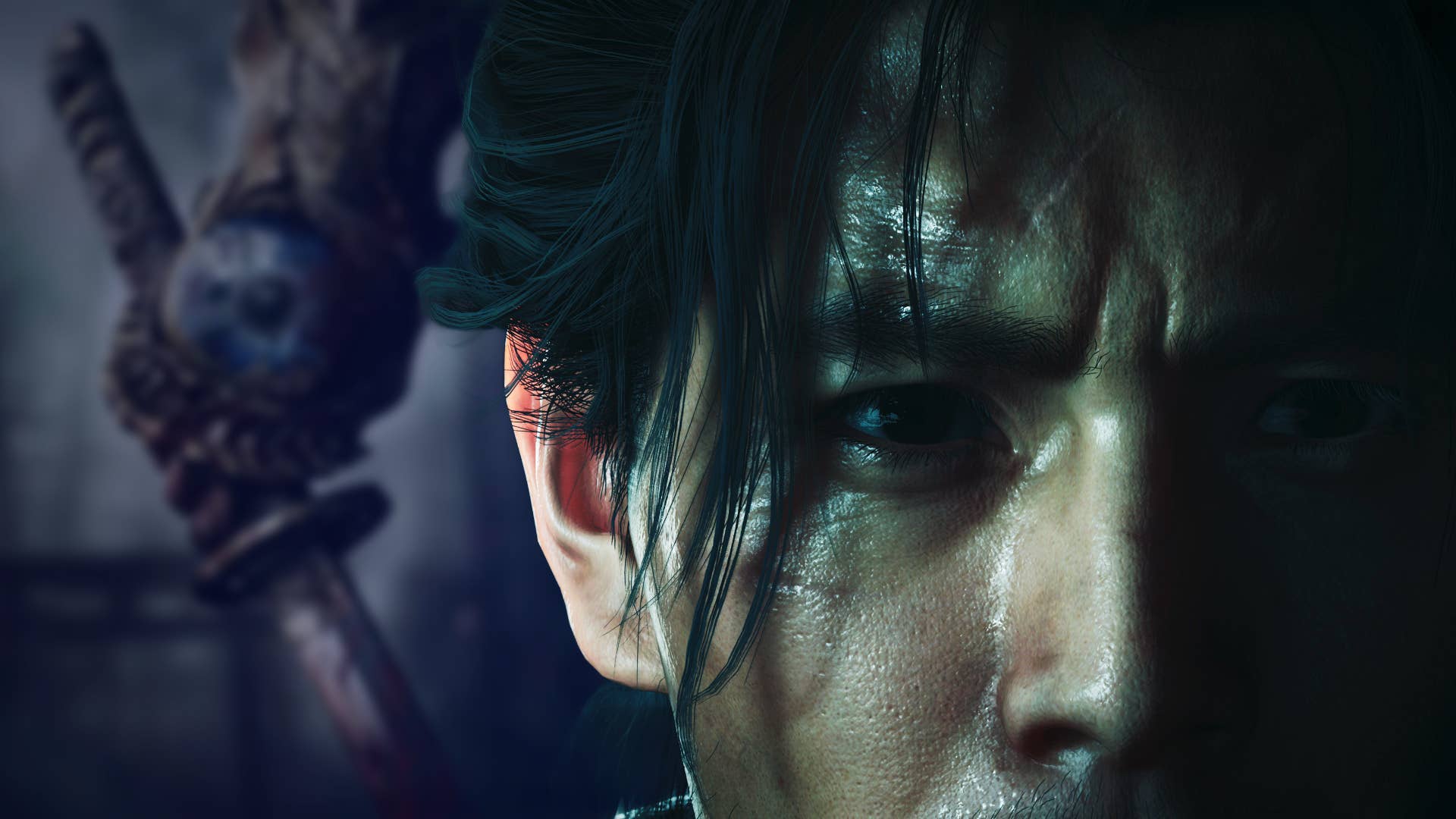

Anthony Dod Mantle has done more to advance digital photography than nearly any artist in any medium, a fact his humility rendered somewhat subtle during a career-spanning conversation I had the fortune of conducting in 2023. He could, nevertheless, casually mention that 28 Days Later constitutes “a historic film” without anyone batting an eye. The sheer aggression of Danny Boyle’s zombie picture only amplifies over two decades of digital images that have largely strived to be clean and, well, film-like. The memory of television ads with those harsh, muddy textures airing across America still boggles the mind.

Around this time did Mantle tell me about plans for a 28 Years Later trilogy on which he would shoot part one and, if all went well, three. (The middle film, directed by Nia DaCosta and photographed by Sean Bobbitt, opens on January 16.) Personal anticipation for it’s been more than I’d typically afford a zombie legacy sequel, and rumors of iPhone-shot footage piqued interest (for others, raised eyebrows). I understood by the second or third shot that Mantle and Boyle would embrace the uncanny effect of consumer tech projected big: these images are lightweight but never frivolous, tactile while alien, and so close to Aaron Taylor-Johnson or Jodie Comer that I started to wonder if scrapped takes found the DP and co. hitting their faces. I enjoyed 28 Years Later consistently and find expectations duly set for a sequel opening shortly, but am mostly waiting to see how Mantle and Boyle go further if they’re afforded the chance.

Mantle and I spoke about this unique process via Zoom, with the legendary DP doing some iPhone operating of his own.

The Film Stage: We talked a bit about 28 Days Later at Camerimage in 2023, and I was not only delighted when you later told me about plans for a sequel trilogy––it’s clear you were excited, too. As 28 Days Later was a watershed moment in digital cinematography, was it understood, when you and Danny Boyle began talking about this film, that something would have to make a similar leap? Does there have to be “a thing”?

Anthony Dod Mantle: I don’t think anything was known. What was very clear between us both––and Danny articulated that much very clearly and very well in our first conversations, which were about three or four months before we went into prep at the end of 2023––as soon as he offered me the chance to do the film, he then went on to very quickly say… I mean, he wasn’t trying to get me; he can get anybody to do his films. But he did say that, if he looks at his legacy of filmmaking––which I personally think is pretty fresh on my Tomatometer; it’s pretty varied, which I respect him for, which I try to practice myself as a cinematographer––he feels 28 Days Later was an example, one of the few films, where he feels the combination and the alignment of narrative intent, content, whatever genre you want to call it, and the realization of it––i.e. the cinematography, the color, the technique, the light, the shadow, the language we used to tell that story––was one of the most satisfying moments he’s had in his collection of films. Which surprised me. I mean, we’ve done some smackers and he’s done some pretty radical things over the years––some perhaps more conventional than others––but we’ve done quite a few things. I didn’t expect him to say that.

So when he said that I took him very seriously, because that leads into the next part of the introduction that he has for me, which was: “Somehow we’ve got to get back there.” We don’t want to go back there, because I still have that camera that I used. It’s an antique and it was good then. We’ve changed. Technology has changed. The illness has changed. COVID has changed the world. The genre of zombie filmmaking and that dystopian world has populated and multiplied by 100 since we made 28 Days Later, and we weren’t the first; we were just introducing some ideas that had never been done before. Anyway, he said that and it was quite a shove in my gut, because within seconds of saying that he said, “You’ve got to find a way of doing something that’s radically, equally relevant and appropriate and different, but honest, for 28 Years Later. What about an iPhone?”

He said the word “smartphone” and I looked at him kind of like Beavis and Butthead––my jaw dropped a bit. I’ve done my fair share of iPhones, and a lot of people in the world over have, and I don’t mind anything; I just have to think it over and marry myself to it and get my instincts in place, artistically and emotionally, to be able to do such a big undertaking, as this film became, and how I’m using the right tools.

That’s what he said, so he knew and I knew. I know Danny for his mind and his strength and opinion, his character. His vision wasn’t clear about exactly how it was to look; his idea was not clear, but the whim and the despotic kind of intent that it should be on something like that was very firm. I chatted with a group––Alex Garland, Danny, Andrew Macdonald––a bit before I just localized into Danny and just stayed on that debate with him, the polemical with him, but he wasn’t really going to budge. I could introduce other ideas. I did contemplate other, smaller… because I like size. I like small size and I like agility and economics; you know me well enough to know that. Not for everything. I can certainly stick a little bloody great camera up and leave it still and create pictures in that way, too, but a lot of the projects that I get attracted to or seem to be doing, they require a certain amount of mobility and agility and intensity.

So his introduction to 28 Years had been that, and I could see a certain logic. I then had to marry myself to the idea and discover what these damn things can do and what they can’t do, and I had to get that technical side of the business into my toolkit in a comfortable way. As much as I could just hold the camera up and say, “Hey, do you want us to put the iPhones in the pockets of the actors and let it go,” he didn’t say yes to that. If he had said yes to that I might have done it, but he didn’t, and I looked at storyboards and I looked at some of his, kind of, premonitions about how the film should be. There’s quite a lot of, not conventional, but familiar––surprisingly familiar––language in there, like rack-focuses and long lenses and this and that, and I don’t associate that with an iPhone, so I had to sort of talk this through with him.

I had to explore, explicitly and very much in detail, every possible way I could use these things––how I could stabilize the image, how I could get into the menus and control the AI-induced or automatic pilot things that go on in iPhones, whatever phone we were going to choose at that stage. I didn’t know, but it became the iPhone 15. He was happy with that, and then I started to develop certain additional, technical additions to the phone to get it into a place where I felt I could pick up any tool, any weapon––anywhere in Britain, in any weather, in any situation, any time of day––and not let him down. And that’s what you don’t want to do with a director, especially when you’ve known a director as long as I’ve known him.

What were some additions that you made to the iPhone?

To cut a very, very long story short: I basically worked with what I call a “semi-naked iPhone,” if you could use the word––as close to the thing you have in your hand now. I tried to base certain techniques and ideas on the simple iPhone as we know. That said, I needed to hold it in a certain way. Because when you have a sensor so close to your body and you’re trying to do moving images, it almost fills your bloodstream. I’ve done that before and had that experience before with small sensors that are filling in the bloodstream. Actually holding an iPhone, if you do what we generally do as consumers, we film––whether we do stills or whether we do movie films––we utilize the stability and stabilizer on the phone. I can’t do that on this film because the stabilization system in any phone, and certainly the iPhone, creates a whole lot of DNA in the background and in the picture that can render post work extremely complicated.

So that’s an immediate alliance I have with my post effects supervisor: that we just had to be very careful, what we did. So internal stabilization was a no-go. I then started running around with an iPhone, just showing Danny what I could do with it, and then the background’s shaky. He didn’t like the wobbling. Which was quite unmaverick of him, but that’s how he saw the film, so I couldn’t just run around with a phone like that. So I had to look at gimbal rules, I had to look at the bloggers, I had to look at the whole massive world of image-makers between the consumer and the 14-year-old with their first iPhone to people like you and me. Sean Baker, etc., etc.

I looked at everything on the market and I eventually decided… because he was also referring to longer lenses, extremely long lenses that do not work on iPhones, and the iPhone’s really not capable of running with images to the level that I wanted. It can, but the kind of images that I needed to do and the images, about certain things, I thought I couldn’t do on the iPhone. So I started to create a system whereby––we wanted to go anamorphic or we wanted to shoot widescreen––so I pulled in a whole lot of the consumer and prosumer front-lens, anamorphic adapters to see how that worked.

I tested that. I tested spherical lenses. I then got hold of another, slightly more developed iPhone––same iPhone, iPhone 15––with an off-the-market, bespoke adapter system which can then attach, through a specially manufactured PL mount, real lenses to that. Which is oddly a parallel to what I did on 28 Days Later with the XL1 and a little spinning adapter, and I put 16mm lenses onto that and that’s how I could control focus––so I somehow get a bit of control in the anarchy of it all. That’s what I did on 28 Days Later, and ironically I think I’ve ended up doing something quite similar on this.

Without thinking about it, I have this tool: a consumer gadget that millions of people in the world know and it can do a lot of things, and thankfully it is making films for people, and certain people are wanting and quite happy to make films on the naked iPhone 15 or 16 with its in-built capabilities with apps. You then program to the phone and you can pretend you’re making films, or you can make films. And people can do that, and I’m really, really happy with that. Apple is having a great deal of success, as indeed I think other film-company manufacturers will too.

But for Danny, it was a basic idea that this small tool––something that could be lying in the field 28 years later in Britain––could render images. It’s not, you know, a philosophical point, but that a thing like that––just a remnant of the society––could be used to make a $75 million studio film, so it would help it in its sheen to feel and look and behave differently, and he knows me well enough to know that that will induce me to do things differently because I inevitably have to. Out of that comes a kind of alphabet; out of that comes a kind of language and a kind of code in the same way that Dogme, through its rules, created a certain language, a certain experience, and there are many other examples of that. This is just one of them, and I think that’s what we’ve tried to do.

So the phones became weapons. I had to travel very light; I had to travel into very inhospitable places. Difficult geography. Difficult weather. Britain in the summer, it’s not exactly recommendable, and ancient landscapes where you can’t drive the trucks in and destroy the nature before you can get the cameras out of the truck. We didn’t really want cranes, apart from some specific scenes. We didn’t really want dollies and tracks, so it was mostly hand-carried by me and hand-operated by me and a B-operator, Stefan Ciupek, and we basically worked together and carried our cameras, and occasionally the larger adapter system on the iPhone––which had a longer lens, like a zoom, which you needed––would go on a set of legs or on a saddle or something or nest in my arms.

You know, we’d work it out. But we were very light and we had to be light, and he wanted the money in the film––which was spent, anyway, because you always hit the wall––we wanted the money to go on, get into places you don’t normally get to, because normally the unit’s too big and you just get a “no” because it’s too complicated. You can’t get people in hotels; you can’t get people near enough. We wanted to go small, like Boy Scouts––you know, with wheelbarrows and climb up these hills and do it like that. So that was a very good argument for shooting on it. It could have been a smaller, still camera––there could have been other candidates––but the iPhone certainly fit into that agenda.

And maybe I was excited when I met you in Camerimage; I can’t remember. I was excited because I’m excited, always, making a film with Danny––and I’d be an idiot not to be, because we go places together that are extraordinary, and this is no exception in a way––but I was probably, when I met you, not completely sure about the tool, what I was going to shoot it on. I think we may, unofficially, have spoken about it, but I wasn’t sure at that stage. But it became clear that’s what it was going to be. [Laughs] And I had a lot of help from a lot of very clever techs around me; I had a lot of help from Apple.

We chose the camera and I chose the iPhone 15 because it had a certain history, already, with Blackmagic, which is a company that manufactures apps, amongst other things; they also manufacture cameras. But they have a thing going already that’s still in development and not necessarily was going in the direction I wanted to go on this film, but it helped me to have a kind of basis of, not approved, but working technology that I could then go in, check out how I could use it. I had Apple help me adapt some of the capabilities the phone has; we had to deactivate some things on the phone. Blackmagic were incredibly helpful, through Jon Carr and Apple, to adjust some things and update some things and adjust some things for us, specifically, which is really interesting.

There’s loads of things in 28 Days Later, like “the infected shutter,” we call it––which is a sort of hectic, staccato effect of the infected movements from the first film––we had to refine that with different tools because the iPhone does not respond or behave like any other digital camera or film camera, obviously. So I had to explore that––I had to find it and start from scratch––and then there were other kinds of violence and other kinds of slo-mo infected in the film which I could work with very happily because I could put the cameras on them, and just stuff like that. That was an interesting present for me.

Last but not least: a very important thing for Danny was this bar cam array that I’ve used. From The Matrix, and used on quite a few film sets and commercials and rock videos, and the great thing about the iPhones is that I could build these arrays with some very clever people. I didn’t do it, but I had a row that were hand-carryable, and we could take them into the countryside and do wrap-around, burst-cam images of violence and serve the specific things that I found really interesting. And Danny was very excited about that.

I mean, yeah: the first kill with the bow and arrow—that feels like the “game on” moment.

[Laughs]

Just a we’re-gonna-have-fun-here gesture. But I was having fun from the beginning, where I’m noticing these folds in the image. It almost looked like scan lines when you would film a computer.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. That’s because there’s a sheen, there’s a layer, in one of the set-ups on the iPhone. It’s not innate to iPhone tech if you shoot with an iPhone straight out of the lens––you know, with the lenses in your phone. You won’t get that. I had that on one of the set-ups I used because I had to convert an image that comes through a cinema lens and goes into the adapter and then––be it anamorphic or a 1.55 anamorphic, or even if it’s spherical; I make spherical an anamorphic––has to travel through the adapter and it gets flipped onto a glass screen where it then gets re-photographed and, you know, then sorted out from anamorphic, if it’s anamorphic, to an unsqueezed picture. And that all goes on in this incredible app in this iPhone which is pretty amazing.

But there is a stage––oddly, a bit like the adapter I used in 28 Days Later––where I had vignetting out on the sides; it was a spinning wheel and that fades the lights out in the corner, like a vignette. So sometimes when I went on the wrong T-stop or was too low in light, or messed with the wrong T-stop, you could start to see that spinning wheel beginning to come into action in 28 Days Later. And ironically we have, on this… it’s just me pushing the envelope. I mean, center-punching: most of the action takes place in the center of the frame because of that fall-off effect which, I mean, it’s been okay for Wes Anderson; he’s had a good career out of that. I’m not a big fan of it generally, but hey: it was good for me to try a bit of center-punching and do something different for a change. [Laughs] So I’m good at throwing things out on the side. So that: well-spotted. Maybe you cheated––maybe somebody told you––but well-spotted.

Well, hand to God, I figured that out myself.

I believe you.

It’s something that many people would work overtime to smooth out, to outright eliminate, but you and Danny are excited by that.

Yeah, I mean: artifacts and refractions and things that keep the audience awake. It’s not just flares. You know, 20 years ago we’d be sitting there raving about flare. Now there’s so much flare, it’s like a fashion––you know, an anamorphic, stripes, the blues and the oranges and the yellows which I don’t really like. There’s lots of things I see are patented and it annoys me, I don’t dig it, I don’t nurture it, and I see very much the sheen of the technique of the film instead of, you know, the narrative and what’s going on among the actors. If I get down that road, I’m my first and worst critic; I don’t want to do that.

So it’s fine to have artifacts. It’s fine to have things that make you suspect and look, perhaps, more tentatively at something because of something else going on. And that could be everything in the sublime beauty––you know, the flares or beautiful, immaculate composition on a massive sensor to what we’re talking about here, and far worse than me. But, I mean, I think there’s a delicate way of doing that where you just intensify the viewer’s process and the viewer’s identification, and a kind of engagement with what’s going on in front of you.

Well, the identification and the engagement for me also is in the proximity to the actors.

Yeah.

I especially think about the scene in the abandoned bus with Jodie Comer, where you’re getting so, so close to her in a way I feel like I haven’t seen a camera achieve.

Yeah, it’s lovely. I mean, I love my actors. The director, officially, always loves their actors, as they should do. Some hate them or they’re scared of them, but they just love them and they should. I, as a camera person who’s grown up in independent cinema, have always been so close to my actors. I come from documentary, where you are incredibly close to people who actually are not actors––who live their life in front of you as it unfolds in front of you and you have to get their respect and technically achieve what you have to do. I come from documentary, which, if you’re used to making documentaries and holding the camera and doing it––and some directors even shoot their own documentaries, of course––you understand the significance and the authority and the sensitivity of what that involves, and actors feel that.

I know actors love the camera, or some are scared of the camera, but the actors who may love the camera, they also feel the camera––they feel the breath of it, feel the breath of the lens. And I like not always getting close, but when I’m doing close-ups, I tend to prefer going in the medium focal lengths, closer to an actor so I’m physically closer and they can feel me––especially when I’m operating––as opposed to being far away with this long poaching. I call it “poaching and poking”––these long lenses where the actors barely know where the lens is. I don’t mind actors not knowing where the lens is or being surprised by where the lens is, but I think it’s great that they feel you and they feel the dance. Chris Doyle always talks about the dance. Many people are used to hand-operating and lighting and directing cinematography. And myself. They know about that. It’s a wonderful thing when something floats and something goes into some kind of cohesion. It’s a beautiful thing.

It’s a beautiful thing and it’s what film can do, and we can talk ‘til the cows come home about what we shot this on and what everybody shoots whatever they shoot on. And that’s great. It’s relevant, and it is about the tools and the people that are merchandising and making these things––the retailers and the suppliers. It’s about all that, yeah, and it’s about light and lenses and sound, but the most essential, fundamental thing is: when you’re in that space––in this case a massive, lonely, melancholic landscape with very, very, very few people, four main people and they’re not there at the time; there’s only ever really three people in the picture, sometimes four––it’s what the camera does and how it rotates and moves around and where you place it, mobile or immobile. It’s where you place that camera, how you place it, and how the actors cohere with the camera. That’s the essence of everything, and it’s the essence of this film.

It is an intimate film, I think; I think it’s a degree of intimacy in here that I haven’t always experienced with my films with Danny. I’ve experienced it before in some of his films, certainly. This certainly is an example of that, and I think it’s an interesting melange––a mix of humanistic, emotional drama and something very horrific and unnerving as well––and that’s quite a genre to achieve. Whether we’ve done it or not, time will tell. But it’s quite difficult. It’s been, directorally, quite difficult for Danny to navigate, and he’s been concerned about it; he’s wondering, often, whether he’s doing the right thing or the wrong thing and I’m standing at his side, so I feel all that and respect him for his dedication and concern for what he does every day.

You guys now––assuming this movie makes some money, assuming the second one makes some money––will make a third film. Do you have concepts of how you’re going to continue advancing your image-making in this third movie?

Absolutely no idea.

Great.

[Laughs] Absolutely no idea. I guess I might be thinking about it, and I’m sure Danny is thinking about it. And I don’t even know… I hope to God that I’m implicated in it. You never know until you know. You never know Danny, and it’s the director’s right to explore his journey or her journey and the way they do it. And you don’t own each other, but I certainly hope that we do do it. You know, I do think about it; I do wonder where we can go because there is a place to go after this, of course. It’s interesting. It’s different. It’s a standalone film; Danny refers to it as a standalone narrative piece.

There is a film coming, which is a certain continuation of what you see in this film, yes, but this film is certainly, as an art form, a standalone film. There’s no real cohesion between this and the next one, apart from the narrative and one or two characters, and then the last one––which we don’t really talk about much yet––will be, to a certain extent, a logical continuation of that. But aesthetically? Too early to say.

28 Years Later opens in theaters on Friday, June 20.

The post “The Phones Became Weapons”: Anthony Dod Mantle on Animating 28 Years Later with Danny Boyle first appeared on The Film Stage.

![‘Buckshot Roulette’ Developer Announces Psychological Horror Title ‘s.p.l.i.t’ Launches July 24 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/split.jpg)

![Puppets, Zombies and Aliens Run Amok in ‘Apocalypse Love’ [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Apocalypse-Love-2.png)

![‘The House of the Dead 2: Remake’ Comes to Switch and PC on August 7 [Trailer]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/hotd2.jpg?fit=900%2C580&ssl=1)

![The Nasty Woody [ANYTHING ELSE]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/anything-else.gif)

![Satire in Action [15 MINUTES]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/15minutes.jpg)

![Strangers in Elvisland [MYSTERY TRAIN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/mysterytrain-theaterruin.jpg)

![United Flight Attendant Leaves Risqué Note for Miley Cyrus’ Ex—”I Was Shakin’ Like a Stripper” [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ua-fa.jpeg?#)

![[Podcast] Problem Framing: Rewire How You Think, Create, and Lead with Rory Sutherland](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/rort-sutherland-35.png)