Paul Laverty on Three Decades of Collaborating with Ken Loach

It’s a brisk March morning in Luxembourg and my conversation with Paul Laverty has turned to Cantona. “Remember that goal he scored, with Brian McClair?” A classic, I agree. “He did that lovely 1-2, looked up, dented the ball,” Laverty explains, whistling the arc, “and then just stood there and stuck out his chest. He […] The post Paul Laverty on Three Decades of Collaborating with Ken Loach first appeared on The Film Stage.

It’s a brisk March morning in Luxembourg and my conversation with Paul Laverty has turned to Cantona. “Remember that goal he scored, with Brian McClair?” A classic, I agree. “He did that lovely 1-2, looked up, dented the ball,” Laverty explains, whistling the arc, “and then just stood there and stuck out his chest. He was everything you could be.” I was curious how Laverty, who wrote Ken Loach’s Looking for Eric, in which Cantona played himself, had approached the player with the script. “I thought, ‘What if this wee guy who nobody recognizes, his children ignore him, he’s just fucking lost?’ I said to Eric, ‘What would it be like if he has the odd spliff when he’s depressed and he speaks to you when things get too much?’ He just burst out laughing.”

No filmmaker comes anywhere close to the fifteen times Ken Loach has had a film in the Cannes competition, an astonishing run that began with Looks and Smiles in 1981 and has supposedly ended with The Old Oak in 2023. Laverty, who was born in India and bred in Scotland, wrote 11 of them, including The Wind That Shakes the Barley and I, Daniel Blake, the films that won Loach his record-equaling two Palme d’Ors. Together, the writer-director team have collaborated on 14 projects since Laverty approached with Carla’s Song some 30 years ago. Many of them I love. Some of them I revere.

We met at the Luxembourg City Film Festival back in March, where Laverty was serving on a stacked jury: Mohammad Rasoulof, Trine Dryholm, Albert Serra––oh, to be a fly on that wall. He’d arrived earlier that day from Edinburgh with a box of Scottish shortbread for the festival’s team. I was told he’d flown economy, despite the festival’s offers of business class. Seated opposite him in an awkwardly plush backroom of the Hotel des Place d’Armes, none of this news comes as any surprise. Kind, genuine, formidable, deadly funny, Laverty might be the most-approachable person I’ve ever interviewed. Over a half-hour we chatted about his early days in the industry, a brush with Abbas Kiarostami, pissing off Michael Gove, and of course The Old Oak, their final, dogged rallying call.

The Film Stage: Hi, Paul. It’s a pleasure to meet you.

Paul Laverty: Hi, Rory. God, this looks like a fucking bordello.

You have to wonder what goes on in this part of the hotel.

Aye. [laughs] But you’d be used to that in Berlin. That’s a good city to be living in.

Ah, yeah. It’s been years. Changed a lot.

I was there a long, long time ago, when Kreuzberg was beginning to change. I’m sure it’s all gentrified now.

As much as anywhere else. And the situation is uncomfortable, politically.

God, yeah. Well, it’s very interesting to be there just now. Everything feels up for grabs. Very unstable. Dangerous.

Feels like the rulebook has changed.

Well, they’ve just torn up international law, for a start. Having said that, I was cheered up to see the ex-Filipino president off to the Hague. So hopefully a few other bastards follow. Did you see that? He’s a guy called Duterte. Killed about 30,000 people. He was that kind of hard man, macho. Said that the fish in Manilla Bay will get fat on the bodies of the dead. It’s fucking great he’s gone.

You spent some time in Central America before working with Loach, is that right?

Yeah, three years. Nicaragua, mostly; El Salvador, Guatemala. Guatemala was right in the middle of war declared via the Contra. You’re quite young, so you probably don’t remember these.

I know the history a bit.

It’s a long story and a tragedy now, what could have been there if it had just been left. 1979, the revolution. They taught their population to read and write. Wiped out polio––not a bad start––but then the US, the CIA, the Contra: just a campaign of terror. But I was in my 20s then, so it was very interesting just to see, and that was where the first film came out of.

You had a small role in Land and Freedom as well, just before?

Well, better to forget about that. [Laughs] It was great fun, I met a lot of people, I met my partner there. Ken asked me just to come along.

Where did you and Ken first meet?

When I came back from Nicaragua I wrote to everyone––I was determined to get the film made––but Ken was the one who responded. Most people didn’t. Why would they? I knew nothing about the film industry. But Ken was just curious and, of course, we connected politically and he was great fun. That was a stroke of luck, but you just have to be thorough. Try talk to everyone, just give it a chance, but it was very lucky, between meeting Ken and getting the film made––it was 5 years. He had all these other projects going on, including Land and Freedom, Ladybird, Ladybird, and Raining Stones.

Then you were rolling.

We didn’t have a five-year plan. One story just led to the next.

Ken Loach and Paul Laverty

Ken was the first person I ever interviewed. 2014, for Jimmy’s Hall. We met in the Savoy. I was young. He was incredibly generous with my questions.

Oh, wow, you’re joking. He’s a gent. Still as sharp as ever, but he’s gonna be 89 next year. It was his political courage and determination that got him through The Old Oak. He did that when he was 86.

Phenomenal film.

That’s kind of you. It was a tricky one, to balance everything. We’d done I, Daniel Blake and Sorry We Missed You before.

It feels like a trilogy. Do you see it that way?

Aye, but it wasn’t planned. But I don’t think you can understand the brutality of I, Daniel Blake if we hadn’t done The Old Oak, because it deals with the massive political loss that was the miner’s strike. That was a critical point in our political history and I don’t think we’ve ever recovered, really. Trade unions haven’t been strong since, you know? I’m not going to romanticize that industry, because people died and it was rough and it was brutal, but there was a real sense of community, and they had an 8-hour day. How many people do you know with that? This precarious work, 12-hour shifts. I mean, the people we met for Sorry We Missed You, you just saw them ground right into the ground.

That’s one of the few films you’ve made together that doesn’t end with a bit of hope.

It’s an interesting point, really. It’s one that we’ve always questioned because just one catalogue of misery after another crushes the human spirit. You have to find stories with hope in them, but you’ve also got to be truthful to the premise and the characters. And there was a brutality to it that was unrelenting, those people were caught in it––many people are and they can’t get out of it––and that was truthful to the people I found. But you know: we didn’t want to finish off that way. We thought we had to find a way of showing how we nourish each other. The Old Oak brought lots of things together. It was one little village, but it was a big canvas.

When I went to these places it became really apparent to me that time was actually a character. I met a lot of the older people and you could talk to them, speak to them, talk to the old ladies––their hair was all lovely and they looked after themselves. They talked about going to jazz clubs and dancing, the music, the things that they did. I met a wonderful old woman who was a nurse during one of the explosions in the 1950s. And she was in her 90s, living by herself, but for all the young people in her area it was an absolute disaster.

Problems with addiction. Lost. The houses around there sold for five grand, people buying them on Monday, selling them on Friday, and then getting people in from prisons, other areas where there’d been difficulties. They created kind of ghettos. So how did we get from that old lady with a real sense of herself to these people in their 20s and 30s with no sense of themselves? You saw it in the street; you saw people’s faces. And then of course that’s where they put the Syrians, you know?

What did they expect was going to happen.

It’s been a problem in Ireland, everywhere. But if it’s the most marginalized people with the least and they feel dumped upon––which they were––they’re just furious, and quite rightly so. So if we’d made the story to be a happy ending, that would be totally false.

And yet there is a grace note at the end of Oak. This moment of solidarity, in spite of it all.

But we met people who did that. Wonderful people with the imagination to do that.

It felt true.

It was a truthful story. I met people who held out the hand of friendship to Syrians with just unbelievable stories, how they survived near-death and torture and missing family, all of that. You always find good people in these places, and I find them quite heroic because I think solidarity and hope have a lot of levels. Hope is about having the intelligence to untangle things, to see things and try and understand them. Then it’s the graft of actually going and meeting people. The beautiful thing is that a lot of these people have become friends now, so it becomes this benign circle. The children get to know each other. And that’s the greatest antidote to the racism: when you get to know people, their friends, and their family. It was a nice note to end off with Ken after 14 films and many years.

Paul Laverty

It does feel like a closing statement.

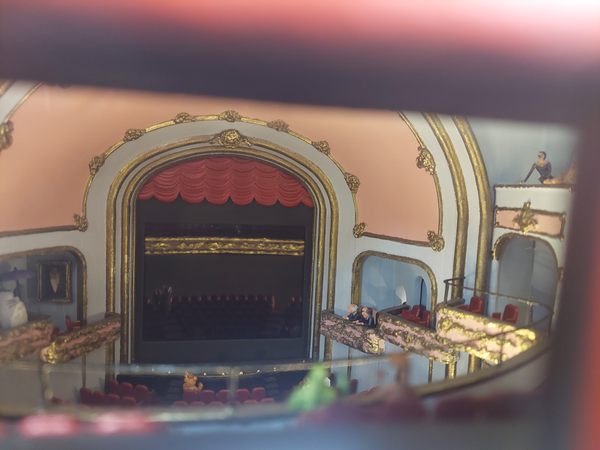

But it has to be truthful. I love that scene with Yarra in the cathedral…

It’s unbelievable. You speak about time being a character. When they’re talking there, you can feel the history of… the planet… or something.

I went to see the cathedral. I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Durham Cathedral, but any old cathedral has it: that sense of something much greater than you, especially when it’s been built nearly 1,000 years ago.

And to parallel that with the thought of what was being destroyed in Syria, or elsewhere––I found it incredibly moving.

Anytime I’m back in London I always take a photograph to send her. Just to thank her for that scene, because she was very nervous about it but she nailed it. That’s the lovely thing about stories, film: you don’t know how they’ll turn out but you go on a wonderful adventure with the people you meet. Dave Turner was great. Dave Jones, too, who played Daniel Blake. The North East has been very kind to us.

So come here, you have a writing credit with Abbas Kiarostami. Tickets. Can you tell us a bit about that? Was there some collaboration on that project?

Well, yes and no. He was a lovely man; I really loved him. But what happened was: they had this idea to put three people who’d won the Palme d’Or or together––Ken, Kiarostami, and Ermanno Olmi. It was one of these silly things; it didn’t really work.

Apples and oranges?

Yeah, but we were all left to our own devices. I’d written a script and it was a really tough one. Then I saw what they were doing and they were also fucking miserable [Laughs] so I thought, “If they do that plus ours, people will be cutting their wrists.” So I just wrote this story with Celtic fans just to kind of cheer it up a bit. A silly idea, really, but it was great fun and a great chance to meet Abbas, whom I had great respect for. He had a film, Where Is the Friend’s House…

Ah, it’s lovely, one of his best. He’s so great with kids.

Aye, I think he was a teacher before. I’m actually going to work with Ramin Bahrani––well, he’s American, but his father’s Iranian.

I actually love a lot of Bahrani’s films. Strange: it feels like I haven’t heard that name in a while.

The last he did was White Tiger, but we’re hoping to do a film together. I really hope that comes off.

It’s a good match.

Touch wood.

So next year is the 20th anniversary of The Wind That Shakes the Barley.

Is it 20 years? My God.

What do you remember about that experience, the first Palme d’Or? Were you in the Lumière for the award ceremony?

No, I was out to do all the press but I didn’t go back.

It must have been a surprise.

It was a brilliant project. I really loved it. And I felt a massive responsibility because you just knew people were going to be crawling all over it.

Was there a bit of that afterwards?

Oh, aye, they were vicious––Michael Gove and all these people. I mean, they ignored it ’til it won the Palme and then they all came out, accusing Ken of being the equivalent of Leni Riefenstahl, you know? “Why does this man hate his country?” But the best one was Michael Gove, that bastard, he became Minister of Education. He said, I’m paraphrasing here, “The republicans always had a peaceful way out but they always chose the backward path.” Our film put the finger on it, because you know, in that election in 1918, 75% of people voted for Sinn Féin and breaking from the empire and independence. And of course they didn’t respect that, and that’s when the pressure started, and from that came the war of independence.

The film put its finger on that false narrative. [In the UK] it’s always been, “We brought the rule of law to the barbarians,” so they were fucking furious. It was hilarious. They were all frothing at the mouth. So that was great fun. I’ll always have great memories of it.

I always wonder how Ken takes the bullets, especially in the more left-leaning press. I mean, I felt the last few years must have really taken the wind out of him. The Labour Party stuff, the anti-semitism accusations.

The antisemitism stuff was very painful to him––first of all because it was totally and absolutely false. I think he was one of the first and one of the bravest to stick his head above the parapet, to say that Israel was an apartheid state. Now look at what we’re seeing.

You should try and take a look at Forensic Architecture. They work out of Goldsmiths. A brilliant Israeli academic called Eyal Weizman. It’s called Cartography of Genocide. They wrote an 823-page report with an interactive platform where they’ve analyzed tens of thousands of geopolitical points, times, and locations, and they’ve built up a pattern of everything, from destroying convoys to destroying the topsoil. It nails it. I think it’s one of the most important documents of our time and nobody is taking them on. It says this is genocide and it’s either being denied or being ignored.

The post Paul Laverty on Three Decades of Collaborating with Ken Loach first appeared on The Film Stage.

![The Sweet Cheat [THE PAST REGAINED]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/timeregained-womanonstairs.png)

-0-8-screenshot.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)