This Must Be the Place: A Queer East Correspondence

In collaboration with the Queer East Film Festival, this year's Emerging Critics cohort offer their responses to the film programme.

In collaboration with the Queer East Film Festival, this year's Emerging Critics cohort offer their responses to the film programme.

This is the first of three pieces published in collaboration with Queer East Film Festival, whose Emerging Critics project brought together six writers for a programme of mentorship throughout the festival.

Qinghan Chen

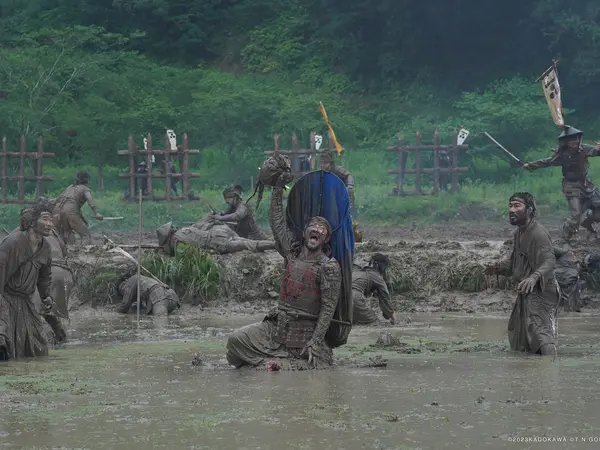

This year, Queer East presents a more defiant stance to the public. I felt it within the first three minutes of Takeshi Kitano’s Kubi, the festival’s opening film. When a headless corpse suddenly appeared on screen, I covered my eyes and nearly screamed out loud. In the next two hours, heads were severed with the flash of blades; homoerotic scenes were folded into the political intrigue. I closed my eyes more than once, retreating into the darkness, anchoring myself emotionally. When a disfigured head was kicked off-screen, the film ended. I fully understood what curator Yi Wang had joked about in his opening introduction: if you feel uncomfortable, please close your eyes.

In the cinema, I never know whether each passing moment will shock or stun me. Moving images pour down like a waterfall, an overused metaphor for queer desire, yet they are still potent enough to shatter my boundaries. But I can choose to close my eyes. With this act, my attention shifts away from the images on screen and turns inward, toward my own body. As a result, I become more aware of my existence. It feels like my eyes are building a temporary shelter, guarding my perception and granting me respite. When I am ready, I can open my eyes and jump back into that fleeting in-between space between myself and the screen. Perhaps I could discover new interactions between films and space.

I experienced a perfect accident after traveling an hour and a half to reach the ESEA Community Centre, where the short film programme Counter Archives was held. The screening room is a narrow space with a skylight, loosely covered by a piece of black fabric. Due to British summer time, the lingering daylight disrupted the images on the screen, making them blurry and erratic. Yet this imperfection created a unique feeling for me.

Six short films awakened buried history through body performance and experimental images. The programme began with artist Cok Sawitri chanting a lament for the missing dead in Indonesia’s 1965-66 genocide, then shifted to the strobe effects of Hong Kong’s street protests. As night had fully fallen outside, the final film, Kitty Yeung’s Private View: Joshua Serafin, appeared on the screen, in which a Filipino artist used their non-binary body to dance into a black swamp, resisting the imperialist ideologies that still exist within post-colonial societies. It was unlike anything I had experienced in cinema. The sequence of the films, together with the slowly fading daylight, gradually restructured the space: public became private, outside turned inward. The daylight eventually became a specific material invading the erased history.

Elsewhere in the festival programme, queer characters also navigate different spaces, seeking shelter for their hidden desire. Jo-Fei Chen’s Where Is My Love? depicts the struggle of gay men in late 1990s Taiwan. In this film, writer Ko (Chih-xing Wen) stands at the crossroads of coming out, hesitating whether to publish his novel about gay love. Here, the interaction between bodies and spaces channels the sorrow that enveloped Taiwan’s queer community at the time. The lonely writer wanders the park at night to meet a mysterious man, later embracing him in the dim bedroom. What impressed me most is their kiss on the street at night, exposed by the harsh light from a lamp post. This moment dissolves the boundary between the public and the private. Finally, the ghost-like lover decides to leave, while the writer chooses to publish his novel and walk out of his room. The place has served as both Ko’s writing corner and a private refuge where the gay couple can freely kiss and embrace. The two men are romantic fugitives and their farewell shows a tragic retreat: they try to flee into a liberating space, but fall back into the noisy public space dominated by heteronormative social expectations.

Another contemporary queer film that explores queer spaces is Jun Geng’s Bel Ami. In a snowy northeastern Chinese town, shot in black and white, lesbian couple Ying Liu (Qing Wang) and Bu A (Xuanyu Chen) walk the street with a secret: they want to have a child with the help of gay barber Shangquan Li (Zixing Huang). At the same time, the women remain wary of Shangquan and install a surveillance camera in a wall clock to monitor his behavior. Via this camera, a strange coexistence of public and private space is constructed. On the screen of a laptop, Shangquan is seen suddenly hugged by a female customer. He struggles and feels embarrassed, as he stands in the empty barber shop. Meanwhile, on the other side, the lesbian couple begins to kiss and make love in the bedroom after laughing at Shangquan’s experience. Compared to the awkward barber, the women are the boldest figures in the film. The final scenes bloom into color as they kiss while posing for wedding photos. Compared to the furtive kiss in Where Is My Love?, this audacious gesture of tenderness signals a small victory.

From the flickering rays of the summer sun piercing through the screen to the wandering queer characters, these movements disrupt spatial boundaries and create a new freedom. Queer East reflects this sense of liberation not only through their subversive programming, but also through their use of alternative screening spaces that exist outside of exhibition norms. While I was there, I used to scribble notes in my notebook, trying to capture details that held traces of freedom. As I write this piece now, looking back at those near-indecipherable marks, I can still sense the joy that filled me in that moment.

Lydia Leung

Many of the films selected for this year’s edition of Queer East draw a clear line between private and public space. Home is often thought of as somewhere private, a place where we feel free to express ourselves, whereas in public we must temper our self-expression for fear of being judged by others. This division is clear in Wang Ping-wen and Peng Tzu-hui’s A Journey in Spring, as we watch elderly protagonist Khim-hok (Jason King) and his wife Siu-tuan (Yang Kuei-mei) move around in their country house. They spend their initial few scenes arguing about everything everywhere, from bus stops and shops to the rainy mountain path leading to their home. Only behind old wooden doors do we really see the tenderness they share, as they laugh at stupid pop songs on TV or struggle to open a stuck jar of plum wine. Their house, with its peeling concrete walls and domestic clutter, feels like a window into a disappearing world, in which hazy snapshots of their private lives gently play.

Tragedy strikes, however, when Siu-tuan suddenly passes away, and Khim-hok is forced out into the unfamiliar urban landscape of Taipei. The camera deliberately isolates him in places meant for building community, as he eats alone in a cafe, sits by himself in a dark park, and wanders through an arcade. Clearly uncomfortable in this rapidly modernising world, he creates a facade through which he faces the public, unprepared to deal with the reality of his wife’s death. Home is a safe place for him, but it also enables him to cling to entrenched beliefs. We share in his sorrow, while also understanding that part of his discomfort stems from his inability to accept his estranged son’s queerness. Khim-hok’s traditional views mark him as a remnant of the past, widening the gulf between who he is in private and who he is forced to be in public, especially given the changing attitudes in recent years towards acceptance of queer people in Taiwan.

What is more public than the history of a nation? In Kubi, Takeshi Kitano takes a revisionist approach, adding elements of queer desire and jealousy to the battles waged between rival warlords fighting over control of 16th-century Japan. We see the capricious lord of Japan, Oda Nobunaga (Ryo Kase), humiliating his vassal Araki Murashige (Kenichi Endō), forcing him to his knees and feeding him a sweet from the tip of his dagger. Inside his opulent, painting-adorned reception room, and in front of his assembled generals, Nobunaga brutally twists the blade inside Murashige’s closed mouth and kisses him as blood spews from the wound. Kitano leans fully into homoeroticism, suggesting that Murashige’s eventual rebellion against Nobunaga was motivated in part by his private, unrequited feelings of love for him.

Even their own homes are no refuge: Murashige goes into hiding with another general, Akechi Mitsuhide (Hidetoshi Nishijima), with whom he is in another overtly queer relationship. In contrast to his reception space, Mitsuhide’s private quarters are simply furnished, lit only by candlelight. But the translucent shoji walls provide only an illusion of privacy: a brief moment of genuine intimacy between these lovers-turned-enemies-turned-lovers is interrupted by the discovery of a spy hiding in the rafters. Great power comes with the caveat of private affairs becoming public knowledge, and nowhere is safe.

The opposite is true for the unusual setting of a cinema box office featured prominently in Lin Cheng-sheng’s Murmur of Youth, where a friendship between two adolescent girls working there blossoms into romance. Seemingly a claustrophobic, public-facing space, the ticket booth becomes a refuge from their turbulent home lives, its velvet curtains allowing them to hide in plain sight. Both girls are named Mei-li, but come from markedly different socio-economic backgrounds: the cashier job enables them to develop a natural camaraderie that would not otherwise have formed.

In this sense, the cinema occupies a unique, liminal space between the public and the private, a venue accessible to all that still affords its patrons a certain degree of privacy. In Close Up magazine, author Dorothy Richardson describes the cinema as a place of “universal hospitality,” separated from the rest of the world with its own behavioural and social rules. The act of film watching is in itself a private act—no one can see through your eyes, or feel what you feel—but having an audience around you indelibly changes your experience. Strangers found kinship by experiencing films with like-minded people, forming micro-communities that dispersed a mere two hours later. To this end, cinemas even served a purpose as early queer spaces, and it’s only fitting to see that reflected in Murmur of Youth. Sometimes a push out of our comfort zones is what we need, and the perfect place to do that is at the cinema.

![New ‘Killing Floor 3’ Dev Diary Delves Into Dark Inspirations [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/killingfloor3.jpg)

![It’s Man vs. Nature in John Boorman’s ‘Deliverance’ [Horror Queers Podcast]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Deliverance.jpg?fit=1600%2C836&ssl=1)

![Simple Slimeballs [DANGEROUS LIAISONS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/dangerous_liaisons.jpg)

![Predator: Killer Of Killers Director Explains Why The Yautja Look So Different In The New Movie [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/predator-killer-of-killers-director-explains-why-the-yautja-look-so-different-in-the-new-movie/l-intro-1749484326.jpg?#)

![Marriott’s AI Will Soon Assign 1.2 Million Rooms—And Decide Whether You Get An Upgrade [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/20221113_160514-scaled.jpg?#)

![Bag Of Coke In The Hallway, Bugs In The Closet—Marriott Still Wants Every Penny [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/hotel-bug.jpg?#)

_J59GzAJ.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)