28 Years Later Review: Danny Boyle and Alex Garland Go Medieval

The first and only time I visited the Catacombs of Paris, I was overwhelmed by the ignominy of the mass tomb. There below the bowels of the City of Lights, hundreds of thousands of those who lived, laughed, loved, and most certainly died found their final resting place not beneath markers of the people they […] The post 28 Years Later Review: Danny Boyle and Alex Garland Go Medieval appeared first on Den of Geek.

The first and only time I visited the Catacombs of Paris, I was overwhelmed by the ignominy of the mass tomb. There below the bowels of the City of Lights, hundreds of thousands of those who lived, laughed, loved, and most certainly died found their final resting place not beneath markers of the people they were. Instead their remains had been transmuted by some odd Frenchman’s macabre sense of decoration. Skulls once filled with thoughts and memories now sat empty and blank. They were building blocks, no different from a child’s crayon, used to slap a heart-shape on the wall.

It’s easy to speculate on whether Danny Boyle and Alex Garland frequented similar sights—and found them delightful if 28 Years Later is anything to go by. Indeed, the pair who deserve credit for reinventing the zombie subgenre more than any other filmmaker since George Romero in 28 Days Later (2002) proved eager enough to get back to their apocalyptic roots that they refused to wait the full 28 years to match their title. And it’s hard to begrudge them since 28 Years Later is a baroque and haunting spectacle that pulses with life, especially when it’s enraptured with the memento mori of it all.

Also worth noting up top for those expecting a film as cuttingly modern as 28 Days‘ vision of a London gone to seed: 28 Years Later is, quite deliberately, something else. In fact, it’s derived from the same medieval pageantry that inspired the Paris Catacombs, right down to the movie’s insistence that there is beauty and serenity awaiting in an oblivion besotted with ravenous, rage-filled monsters. Although to find that tranquility, it might be best to avoid having an infected chap rip your head off, spine and all. Which, believe it or not, happens a lot more frequently than you might expect these days.

Despite the movie’s title, 28 Years Later opens briefly before the world falls apart in 2002. This retro-ness is referenced by sweet, innocent children seen watching the Teletubbies while their parents attempt to keep rage-fueled “zombies” out of the house downstairs. It won’t save them. This genuinely gruesome prologue acts as a contrast for everything which follows after a long flash forward to 2030. There only pockets of humanity still endure in heavily fortified conclaves scattered across the UK.

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne—a real speck of land near the border of England and Scotland, and which is only accessible by a causeway that vanishes with the tide—is one such community. Compared to the doomed city slickers of 28 Days Later, these inhabitants’ lives are positively medieval, which Boyle makes explicit with pointed cutaways to old English costumed dramas from the early 20th century interspersed throughout the first act of his film. The villagers’ lifestyle is also fairly agrarian and peaceful, complete with farming, a castle, and a diligently guarded wall and gate. Their one and only pub even keeps a place of honor for old Queen Lizzy’s coronation portrait. This peace is broken, though, every time a child of the community must come of age and execute a rite of passage: they must learn how to forage and survive on the mainland.

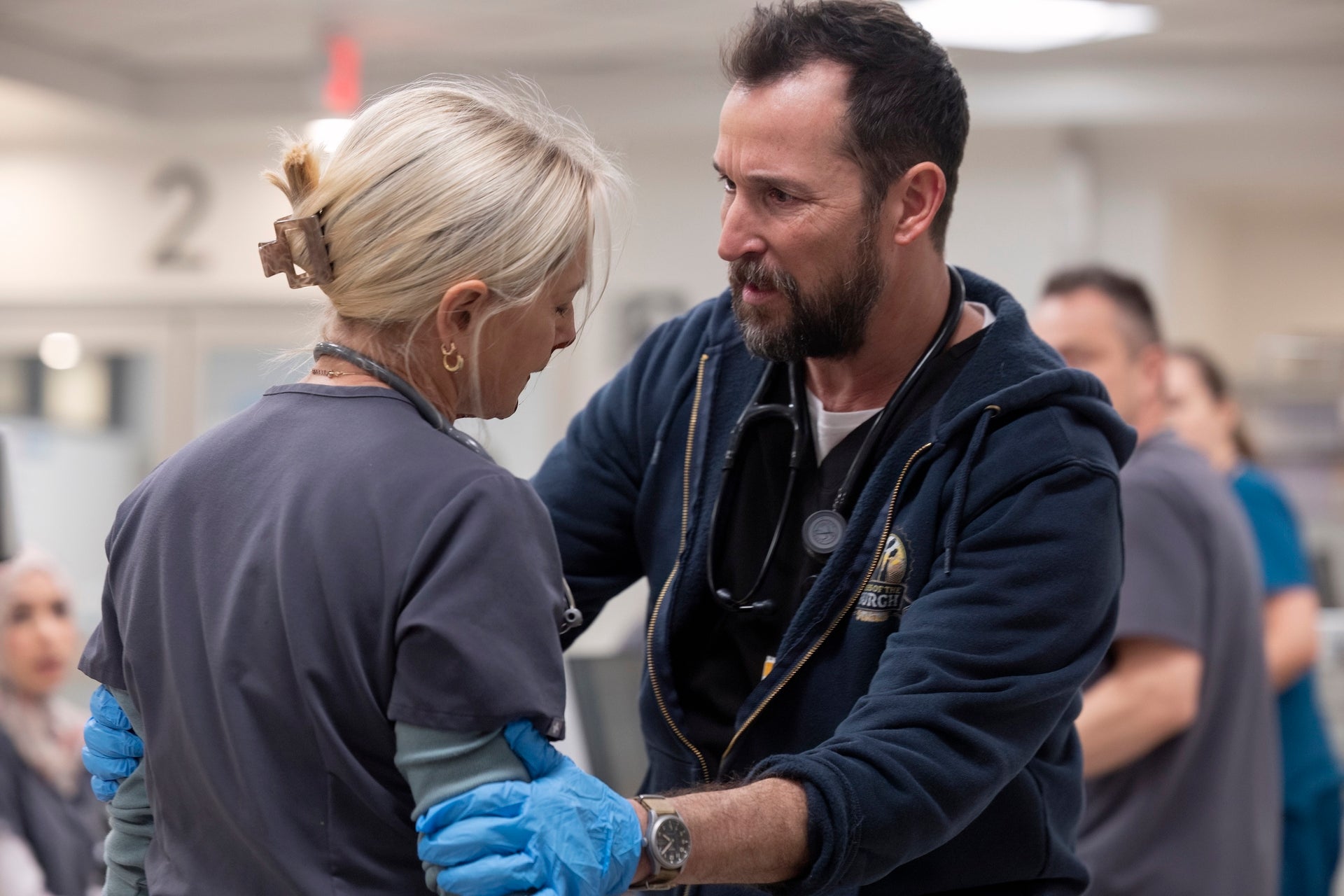

Spike (Alfie Williams) is one such child who recently turned 12 years old. That is apparently a tad early to earn one’s stripes by killing infected cretin with a simple bow and arrow, but his father Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) is insistent that now is the time to test the lad. To be fair, Dad likely feels an added need to prepare his son for the cruelties of the world due to the boy’s mother Isla (Jodie Comer) coming down with an undiagnosed illness that leaves her bedridden and forgetful. No one knows exactly what’s wrong with her; their community doesn’t have a doctor. However, the problem with teaching a boy how to survive (or think he can survive) on the mainland—where new uber-strong infected monsters called “Alphas” run rampant—is that the boy might get ideas about helping his Mum. Such flights of fancy can even lead you to a temple where the bone-artwork is multitudes bigger than anything found beneath the streets of Paris.

The most immediately striking thing about 28 Years Later is how liberating it appears to be for Boyle, who returns as both director and now co-writer with the original film’s scribe, Garland. The aforementioned opening attack set during 2002, and pretty much every scene with the infected thereafter, harkens back to the kinetic editing propulsion that Boyle used to define British indie cinema in the late ‘90s and early 2000s in cult classics like 28 Days Later and Trainspotting (1996).

Yet while these flourishes are relatively frequent, they are neither the real creative impetus nor the ultimate effect achieved by 28 Years. Whereas their previous film was about bringing modern 21st century urgency and verisimilitude to the zombie genre (albeit these are not technically zombies), 28 Years Later is really concerned with the pastoral life of Britain’s past reclaiming the green isle like an overgrown piece of ivy. Or a virus.

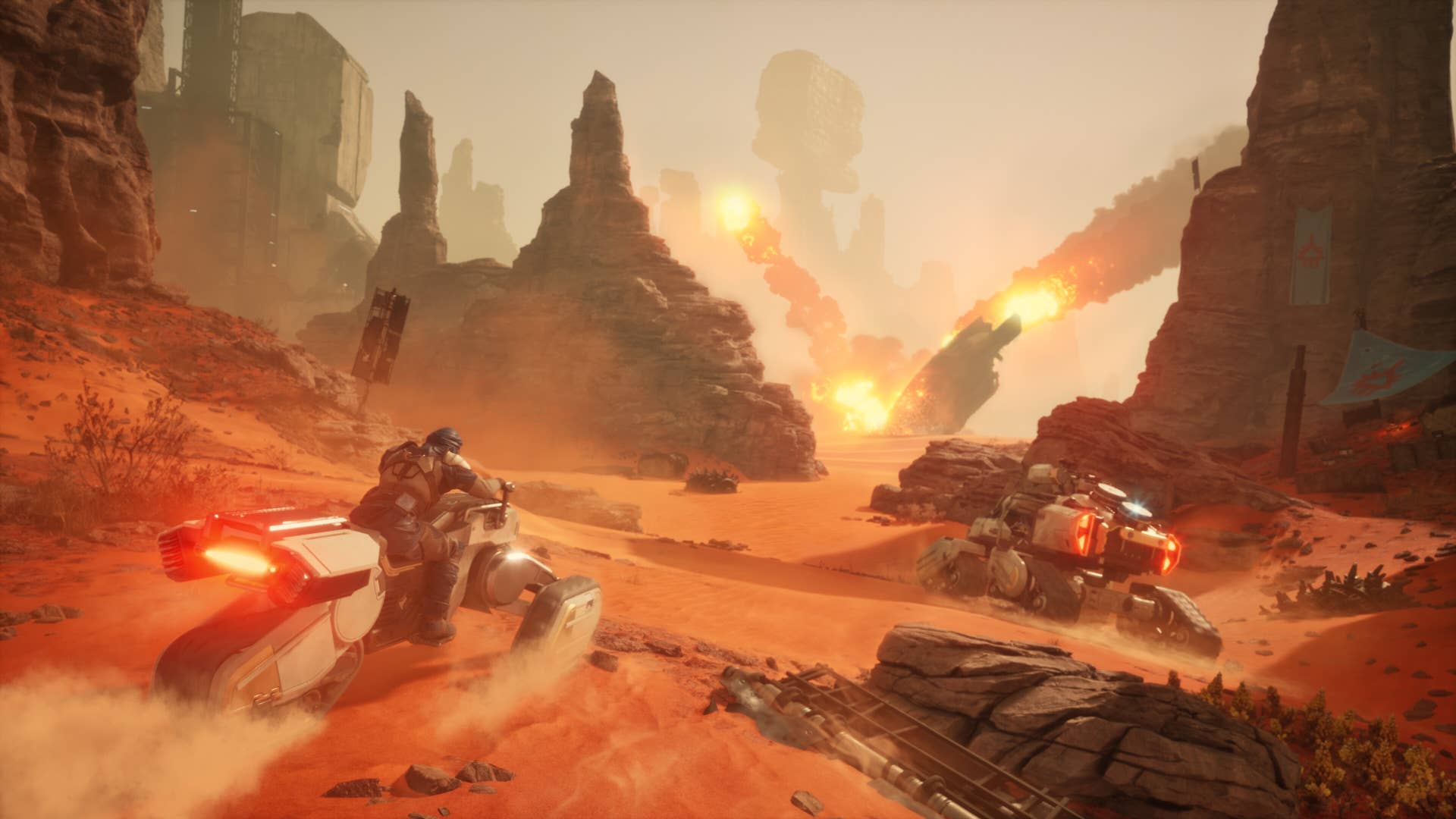

28 Years Later imagines a future that inherently taps into 21st century fantasies about returning to the “simplicity” of the past, despite that simplicity also resurrecting a provincial lifestyle where to leave one’s home by even a few miles is to court death itself—literally so in a film where those still infected three decades on from the initial outbreak have grown either enormously rotund from feasting on the animals of the woods, or transformed into hulking brutes who might be mistaken for video game minibosses, right down to their penchants for ripping out spines. (Think more Resident Evil than The Last of Us.)

In effect, the film becomes a meditation about family and community, hearth and kin, and what happens if a civilization really returns to the “good old days” where education is more about how to use a weapon than a book. It also therefore becomes a character study about the toll this takes on the central family.

Taylor-Johnson does fine work as Jamie, a father who yearns for what is best for his son, but due to the direness of the world he’s raised this boy in, Jamie seems infected with a rage that needs neither bite nor blood contamination to spread. It’s the best mainstream showcase for Taylor-Johnson’s talents in a long while, but the performance that really transcends is Comer. It is no minor feat to ask a talent of her generational quality to play a character who spends much of the film in bed and the rest of it suffering. Yet there is a brittle steel beneath Isla’s constant looks of confusion and frustration. When the flickers of recognition catch wind, the impression will be undeniable to anyone who’s seen a loved one’s mind slip away.

The desperation of her situation is the motivation for the film’s true protagonist, a 12-year-old who has been raised in the shadow of death but never taught how to confront the hard truth of an empty skull. The choices made by such a lad will undoubtedly frustrate some audiences, and yet onscreen characters who might voice those concerns will eventually reveal the implicit dangers of such callowness.

To say anything more of the story would give too much away, but rest assured 28 Years Later finds an intriguing route to acknowledge how this dystopia exists in a world where continental Europe has survived by leaving the UK to its grim, abandoned fate. It also features a fantastic, enigmatic role for Ralph Fiennes. All elements converge in weaving a larger tapestry that, like so many of Garland’s recent scripts, from Devs to Civil War, seems to dread a future for our world that’s rooted in the mistakes of the past.

That tapestry, it should also be said, is left frustratingly incomplete. It’s already been announced that 28 Years Later is the first part of a trilogy that continues in next year’s 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple (that one will see Candyman’s Nia DaCosta stepping in as director). Hence this film unsurprisingly concludes mid-story. In truth, it concludes right when the story is reaching its most interesting development. While obviously by design, it also feels like a concession to some of the same quirks of the modern world that Boyle and Garland seem otherwise intent on skewering.

The ending, or lack thereof, is labored, but it only stands out when so much else of the film flourishes like its raging virus. Fortunately rage is not the culmination of its choices. The film is instead keen on the beatific surrender of Hildur Guonadóttir’s score, which can aurally envelope the image of a boy staring at a monument of skulls. It is a movie content with finding perverse tranquility in the full weight of nothingness’ shadow, connecting the present to the past… and the eternity to come.

28 Years Later opens on Friday, June 20 everywhere.

The post 28 Years Later Review: Danny Boyle and Alex Garland Go Medieval appeared first on Den of Geek.

![Satire in Action [15 MINUTES]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/15minutes.jpg)

![Strangers in Elvisland [MYSTERY TRAIN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/mysterytrain-theaterruin.jpg)

![The Most Intelligent American Movie of the Year [THE BIG RED ONE: THE RECONSTRUCTION]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/the-big-red-one2.jpg)

![Cinematic Obsessions [THE GANG OF FOUR and SANTA SANGRE]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/labandedesquartre.jpg)

![She’s the World’s Tallest Woman—It Took Buying 6 Airline Seats Just to Get Onboard [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/worlds-tallet-woman-flying-turkish.jpeg?#)

![[Podcast] Problem Framing: Rewire How You Think, Create, and Lead with Rory Sutherland](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/rort-sutherland-35.png)