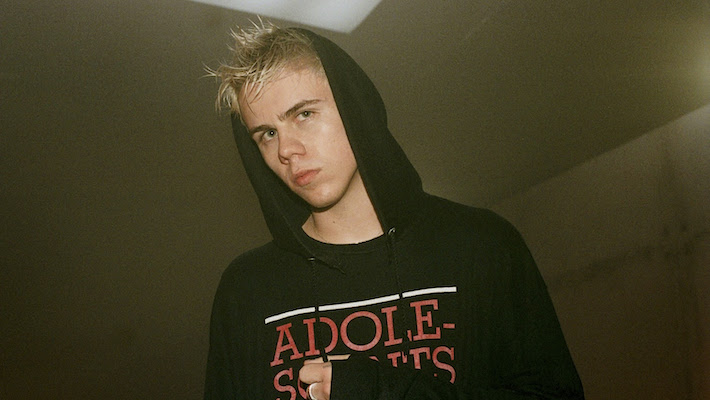

‘Adolescence’ Creator Stephen Graham Explains Why He Refused to Blame Eddie for His Child’s Crime: ‘We’re All Accountable’

"I really wanted the audience to come away thinking, 'That could happen to us,'" says the actor-writer-producer The post ‘Adolescence’ Creator Stephen Graham Explains Why He Refused to Blame Eddie for His Child’s Crime: ‘We’re All Accountable’ appeared first on TheWrap.

This Emmy season has seen the rise of lots of strong new programs that could well attract the attention of voters, from dramas like “The Pitt,” “Paradise” and “Landman” to comedies “The Studio,” “Nobody Wants This” and “The Four Seasons.” But nothing has made the impact of “Adolescence,” the four-episode British limited series about a 13-year-old boy who is arrested in the stabbing death of a classmate.

The series, created and produced by Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham (who also stars as the boy’s father, Eddie Miller), has had more than 140 million views on Netflix, making it the second-biggest English-language series ever on the platform, trailing only “Wednesday.” It also topped all other shows by winning three awards at the Gotham TV Awards: Breakthrough Limited Series, Outstanding Lead Performance in a Limited Series for Graham and Outstanding Supporting Performance in a Limited Series for Owen Cooper, who plays the boy and had never acted professionally before being cast.

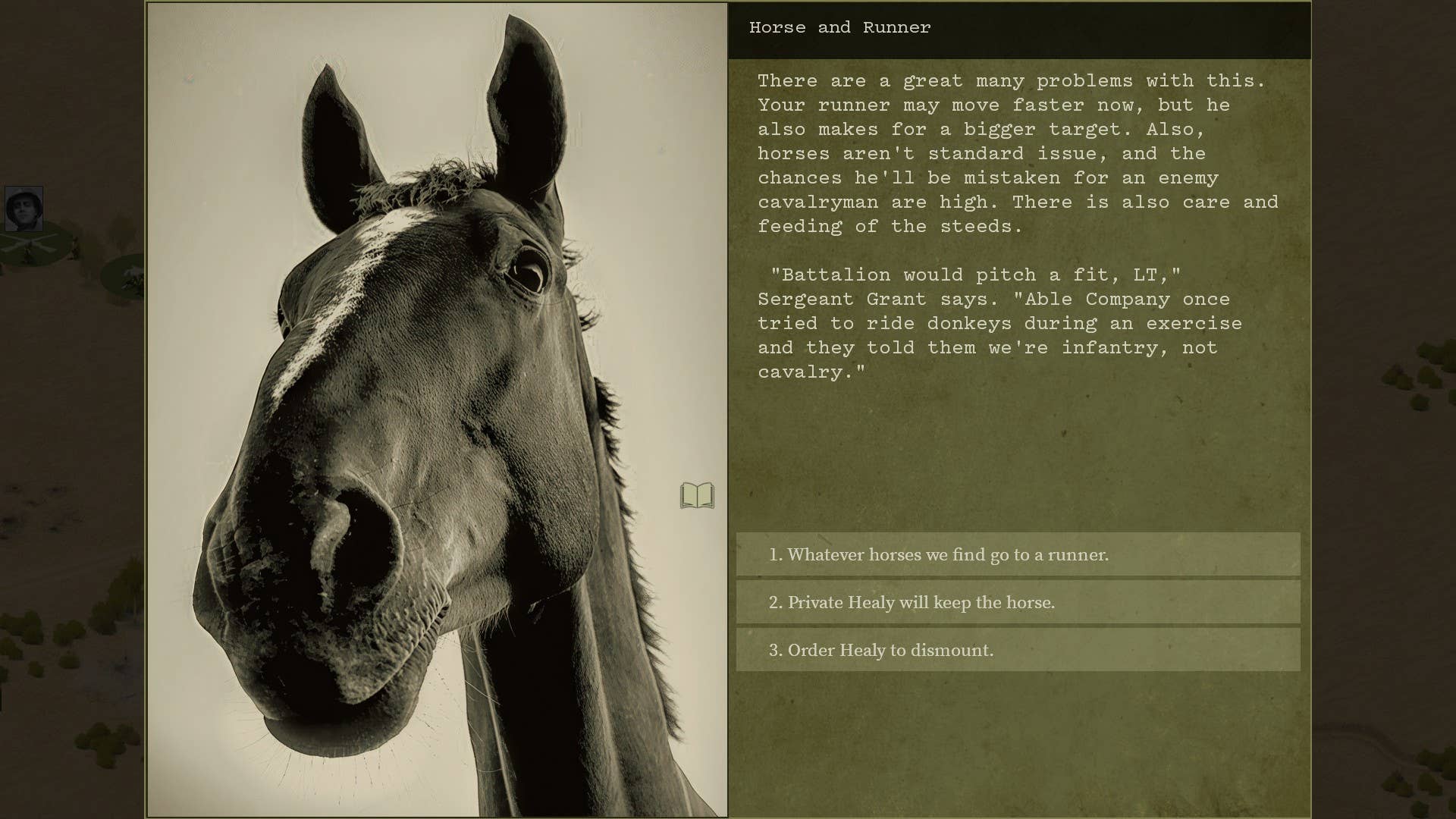

All four episodes in the limited series were shot in single, uninterrupted takes of at least 50 minutes, shot twice a day for a week after two weeks of rehearsal and blocking. The first episode moves from a car to the Millers’ home, where son Jamie is arrested, to the police station where he’s detained and interrogated; the second roams the halls of the school Jamie attended as detectives try to understand a brutal crime that seems connected to the online incel culture of frustrated young men; the third is a harrowing conversation in jail between Jamie and a psychologist played by Erin Doherty; and the fourth follows the Miller family a year later.

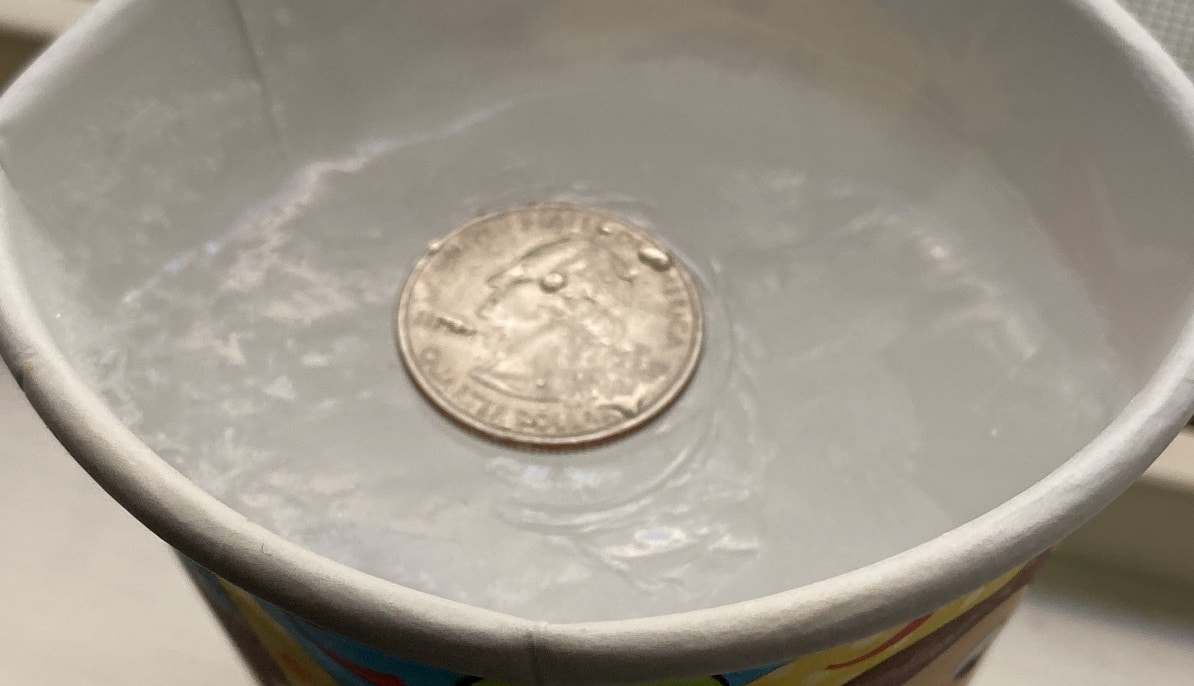

“Our objective was to create something that would spark conversation, and it really has done that,” Graham said in an interview with TheWrap. “We threw a beautiful stone into a pond, shall we say, and the ripple effect has been…” He paused. “Well, we didn’t expect it to create a bit of a tsunami, do you know what I mean?”

That tsunami puts “Adolescence” in a similar spot in the Emmy race to last year’s “Baby Reindeer,” another provocative British drama on Netflix. TheWrap’s Limited Series/Movies awards magazine devoted its cover story to Cooper, but we also spoke to Graham about the genesis of the show, its wrenching final scene and why it never tries to explain the crime at its center.

When I spoke to Jack Thorne, he said that one of your stipulations from the beginning was that you didn’t want to do anything that blames the parents. What were your priorities in telling this story?

I just wanted it to be a story that people could relate to. I think when we see these stories on the news, we always think, “Well, that happens to other people.” And I just really wanted the audience to come away thinking, “That could happen to us, or it could happen to someone I know.” To have that kind of relationship with it, where it’s a plausibility.

I didn’t want Jamie to come from a family where his father had beaten him as a child or was violent with his mother or his sister. I didn’t want his mom to be an alcoholic, or for somebody in his family to have molested him in any way, shape or form.

As a conventional kind of storyteller, I understand that. But I wanted to look at everything and say maybe we’re all slightly accountable, the educational system as well.

The story was inspired by a few specific incidents?

There were a couple of stories. There was a particular incident in Liverpool, where I’m from, with a young girl who was 12 who was stabbed to death by a 15-year-old boy. It was him and three of his friends in the city center. That was the case where I just thought, “Oh my God, this is something beyond me now. I don’t understand it. How can a young boy — and he’s still a boy, they’re not men – how can a young boy do that?” And then there was a girl who was trans, whose name was Brianna, and she was lured into a park in Leeds by a boy and a girl and they brutally stabbed and murdered her as well. That was when I thought, “This thing is spreading. There’s something not quite right with what’s happening to our youth today.”

Those were the stories that I based my idea on, and that’s what I wanted it to be. I wanted it to be a case where you think, “That could be my neighbor, or that can happen in my village or my city.”

We were never pointing the finger at anybody. We merely wanted to give an honest view and a perspective of what things could be. If you look at it, everybody is accountable within our story.

And you knew right away that the story would lend itself to the format of using episode-length, uninterrupted shots?

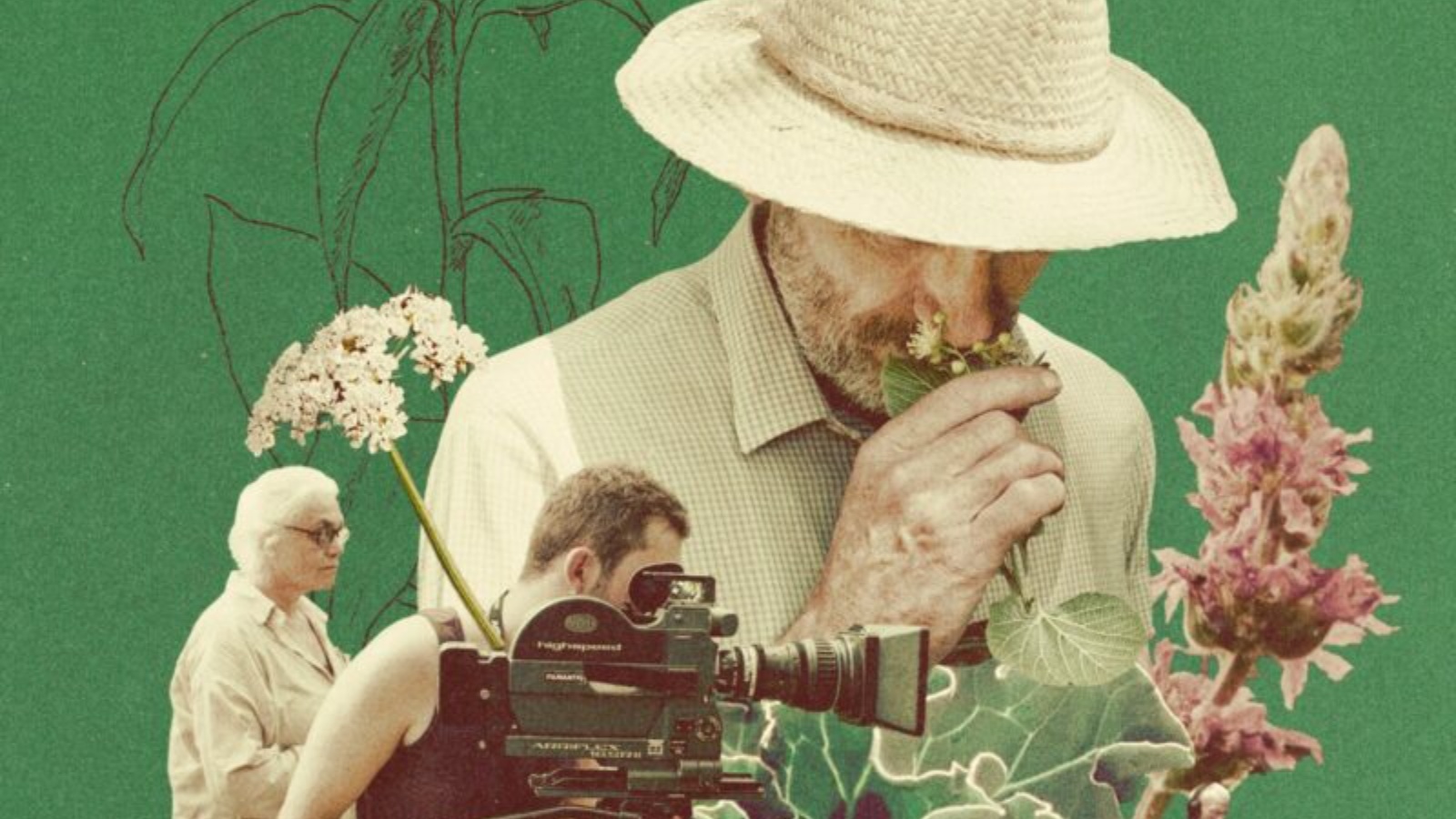

Yeah. Because we did a film called “Boiling Point,” myself and Phil Barantini, our director. It started off as a short film, just to try and get Phil an agent, and then it ended up being a feature. It was extremely successful in its own right. It was nominated for best British film at the BAFTAs, Phil was up for best up-and-coming director and I was nominated for Best Actor.

And I knew straight away, from the first episode, that I wanted to grab the audience. I knew it was going to be a police raid on a house. I felt like the energy and the movement and that kinetic kind of ferocious camera work would be taking us into a house. I always envisioned myself being in there and the audience thinking that the police were coming for me, obviously, and then them going past me into the bedroom of a 13-year-old boy. I just knew that from that moment we would be able to grab the audience straight away. And then basically, through the technique and through that one-shot format, you have the opportunity to take the audience with you and have them realize what is happening in real time, the same way that the parents are realizing what’s happening at the same time.

Ultimately, we always wanted the audience to think there’s no way this boy has committed this horrendous crime. And that was the beauty of Jack’s writing. Jack constructs characters so beautifully and so fully dimensional, do you know what I mean? There’s that moment when the boy gets out of bed and he’s wet himself. As an audience, you know that a 13-year-old boy would do that if he is getting guns pointed in his face first thing in the morning.

At the end of the last episode, we go back into that bedroom with his father, your character. We’ve gone through this journey for four hours, and then it comes down to Eddie and his wife sitting in their room trying to make sense of what has happened and why. And then Eddie goes into Jamie’s bedroom and picks up a stuffed animal, and it’s an absolutely wrenching way to end the series. When you were filming that scene, did it feel like something special?

When you are in it, you’re not really thinking of it. Don’t get me wrong – there are moments within Episode 4 where I sat in the van and we were having a conversation on the way to the hardware store, and there might be a little pause or something, and in your head you kind of go, “Oh, this take’s going really well.” And then you instantly think, “Get out, get out, get out of your head.” There are those slight moments along the way, but then they dissipate completely.

With respect to that last episode, let’s not forget that last episode was also our last take. That was take 16. I don’t mean to sound pretentious in any way, shape or form, but there was a tangible energy about that whole thing. We’d spent the summer together, and I’m not just saying this, but it was an absolute beautiful job to do. Every single member of the crew felt valued because everybody was on their A game for every single take.

For that last take, myself and Christine [Tremarco, who plays Eddie’s wife] just really dived into it. It was the last take, it was Friday afternoon, the sun was out and we were finishing that night. There was a wrap party set up for later on. We knew that was it was all over after this particular take, whether we got it or we didn’t.

And after, a lot of the crew were coming up in tears. That was our final episode, and we knew that that had something.

The post ‘Adolescence’ Creator Stephen Graham Explains Why He Refused to Blame Eddie for His Child’s Crime: ‘We’re All Accountable’ appeared first on TheWrap.

![‘Predator: Killer of Killers’ Directors on the Anthology Format and Historical Accuracy [Interview]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-05-19-121021-1.jpg?fit=1694%2C802&ssl=1)

![Vampiro Returns — To Build a Cult on the Airwaves [Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vAMPIRO-bANNER-TEMP-1024x576.png)

![Metaphysical Pop [THE MUSIC OF CHANCE]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/the-music-of-chance-patinkin-kid-1.jpeg)

![‘I Don’t Understand You’ Directors Brian Crano & David Joseph Craig On Working With Nick Kroll, Andrew Rannells & Making A Vacation Horror Comedy [Interview]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/06125409/2.jpg)

![United Quietly Revives Solo Flyer Surcharge—Pay More If You Travel Alone [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/united-737-max-9.jpg?#)