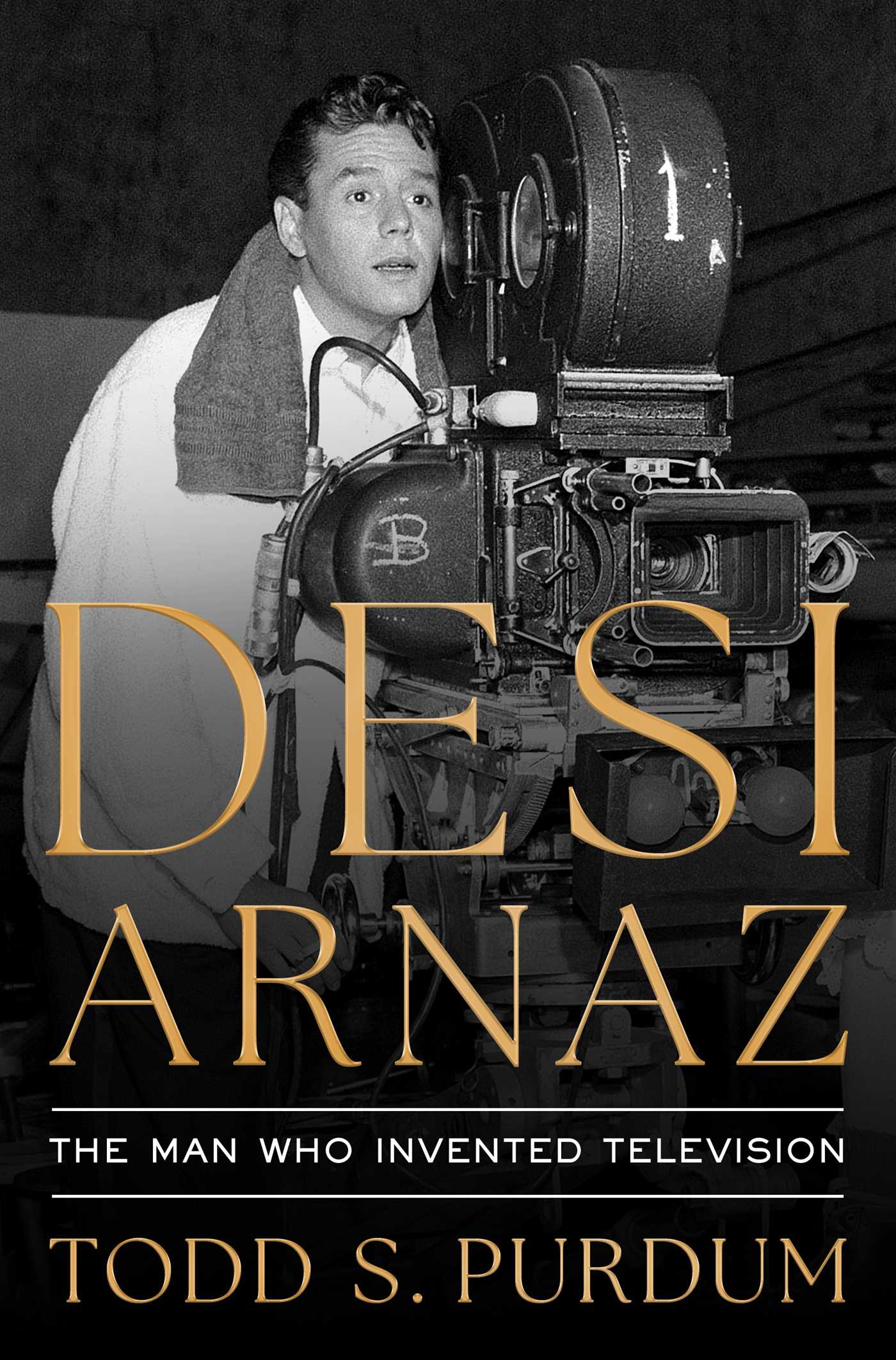

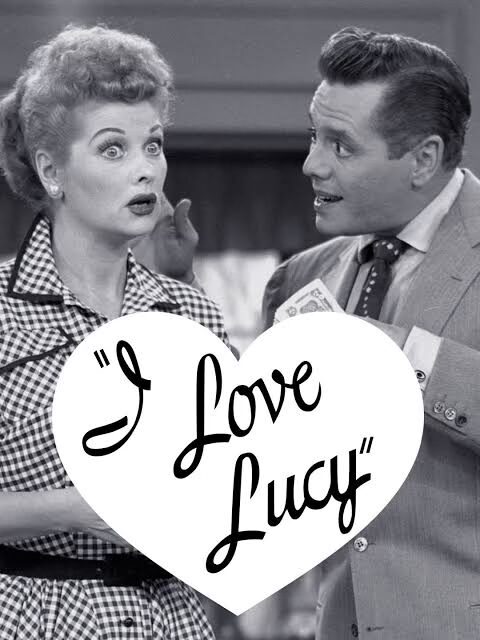

A Great Businessman in the Persona of a Wonderful Entertainer: Todd Purdum on Desi Arnaz

An interview with the author of a new memoir on the pioneering actor, producer, and husband of Lucille Ball.

Todd Purdum’s new book is a biography of Desi Arnaz, described in the subtitle as “The Man Who Invented Television.” Most people today associate him with the straight man for his then-wife, Lucille Ball, in the classic “I Love Lucy” sitcom, and the character he played, nightclub singer Ricky Ricardo. But Arnaz’s most enduring legacy was behind the scenes, in the technological and strategic innovations he insisted on, as well as the business he built. His Desilu production company ultimately took over one of Hollywood’s most prominent movie studios, RKO. Beyond “I Love Lucy,” Desi Arnaz was behind or played a role in television series from “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” “The Andy Griffith Show,” and later “Mission: Impossible” and “Star Trek.”

In an interview, Purdum talked about why he thinks of Arnaz as “a great businessman in the persona of a wonderful entertainer,” the innovations Arnaz pioneered that are still part of television production today, and what he found in the meticulously assembled archive maintained by Lucie Arnaz.

You dedicate the book to the late Doug McGrath, who suggested you write about Desi Arnaz. How did that come about?

I left The Atlantic in a pandemic-related layoff. But I was 60 years old, and it provided an opportunity for reflection on what I should do next. On the 50th anniversary of “I Love Lucy,” Doug had written a piece for the New York Times Arts and Leisure section. They were twinned pieces. Joyce Millman wrote one about the genius of Lucy, and Doug wrote one about the genius of Desi. He told me that he felt Desi’s contributions had always been minimized and misunderstood, and that he was, as the straight man, the fulcrum on which the whole thing turned. Lucie Arnaz, whom I met through mutual friends, was very willing to cooperate because she, too, has long felt that her father’s contributions to the success of “I Love Lucy” and to the model of Hollywood and television have long been misunderstood. She invited me to look at what was a very well-organized family archive of letters, documents, her father’s high school report card, his alcohol rehab discharge papers, medical records, and correspondence. She just set up a table in her garage and gave me carte blanche, cooking me breakfast, lunch, and dinner for the weekend and saying, “See what you can find.”

Simon & Schuster bought it, and I’m so, so grateful and glad they did, because they saw that there was a story to be told there, and they trusted me to tell it, even though I’m an aging WASP from Illinois.

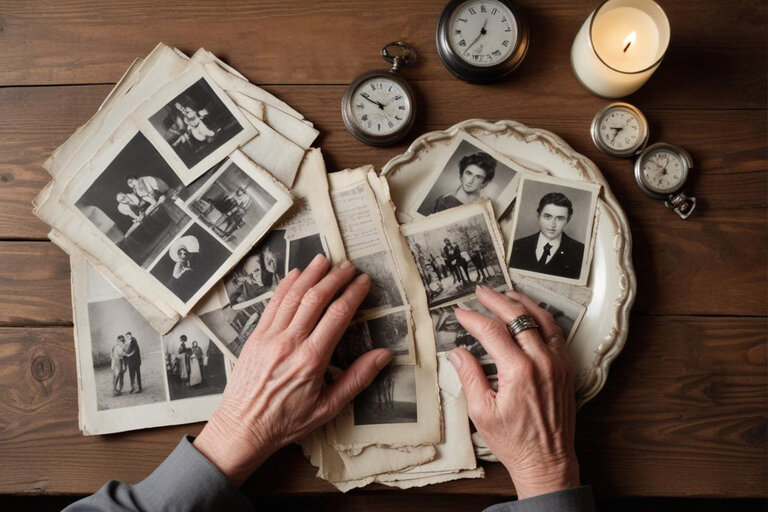

I could tell from reading the book that the archive was a real treasure trove. What did you find there that you thought was especially valuable for understanding Desi Arnaz?

There were letters from a psychiatrist they consulted, Smiley Blanton, who was an associate of Norman Vincent Peale in New York and had what would surely now be considered an unholy alliance between uplifting mid-century modern Christianity and Freudian psychiatry. Freud himself had analyzed the guy, and he’s talking about Desi’s Rorschach test. There were also 80-some scrapbooks in the Library of Congress, most of which had been compiled by Lucy and her secretary.

Lucy had saved everything, really, from early in her career—press clippings, pictures, correspondence, and so on —and posted them in these giant scrapbooks. And Desi’s father in Cuba had compiled four fat scrapbooks of his own. There were also some papers of Desi’s. In retirement, he briefly taught at Cal State San Diego, and that’s where some of the drafts of his memoir were, although there were other parts of the draft in Lucie’s garage.

It was really an act of enormous generosity and faith on her part to trust me with this. She made it clear from the beginning that she wanted to see the manuscript, but she wasn’t going to exercise any editorial control over it or any veto. When it was all done, I sent it to her, and she left me a very long, generous voice memo in which she said she pictured her father reading over her shoulder. And at the end of the book, he had said, “OK, fair enough, fair enough.” And I thought, as a journalist, you never want someone to totally like everything, and you don’t want them to be upset about it. “Fair enough” was the answer you’d like to have.

You quote Norman Lear in calling Desi Arnaz “a great businessman in the persona of a wonderful entertainer.” No one would call him a brilliant actor or put him in Lucille Ball’s category as a comedian. What were his strengths as an entertainer?

The one thing that Desi clearly had was star quality. Some of it, when he was younger, especially, was definitely sex appeal. He was stunningly good-looking as a young man, which we tend to forget about. By the time of “I Love Lucy,” he’d already thickened up a little bit in the face. And in the later years of “I Love Lucy,” he was putting a black rinse on his hair. And he wore elevator shoes. And he had a lot of charm. What he lacked in vocal skill or musical skill, he made up for in taste and oomph. He had a lot of sparkle and a definite roguish quality, a twinkle in his eye. A little bit of the bad boy in him always.

And then ultimately, by the time of “I Love Lucy,” he had developed into a very, very good straight man, which is a hard thing to do. You have to be content not to get the glory, but to be the lever that sets up the joke that that snaps satisfyingly closed in the punch line. But you’re the one who’s also the eyes and ears of the audience, which is one of the points that Doug had made in his piece.

He obviously had boundless self-confidence. He was raised to be a prince, the only child in a wealthy and powerful Cuban family. He had the fortunate features of childhood, where he was raised with high expectations, believing he was part of the ruling class. However, at 17, he became a penniless refugee in the US. He had enormous drive to succeed, to reclaim some of that success, and confidence, as well as fearlessness. “I’ve lost everything, so what else are they going to do?” you know? He had that sense of “I’ll try anything.” And the only sad thing was that by the end of his life, he couldn’t really come back because he’d diminished his talents through drink and other things. His final attempt at a comeback was not successful because the industry no longer trusted him.

Your chapter “Lightning in a Bottle,” about the origins of “I Love Lucy,” is one incredible revelation after another. Part of it is timing, part is technological innovation, and part is brilliant business judgment.

As the book makes clear, he did not do them all alone. Later, when he wrote his memoir, he was so determined to reclaim credit for himself that he felt he’d been denied, there were times when he overclaimed. But he was certainly a pioneer in the use of all these techniques.

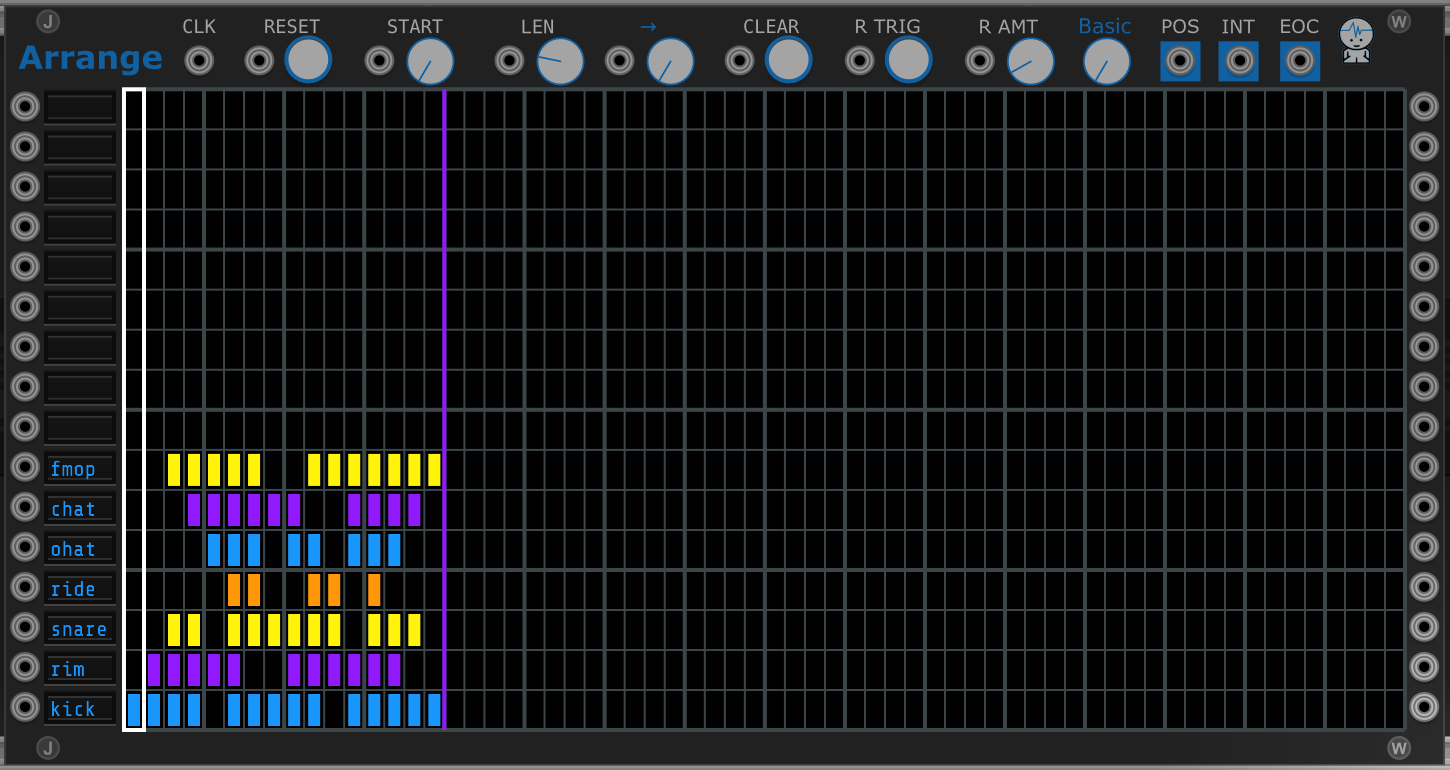

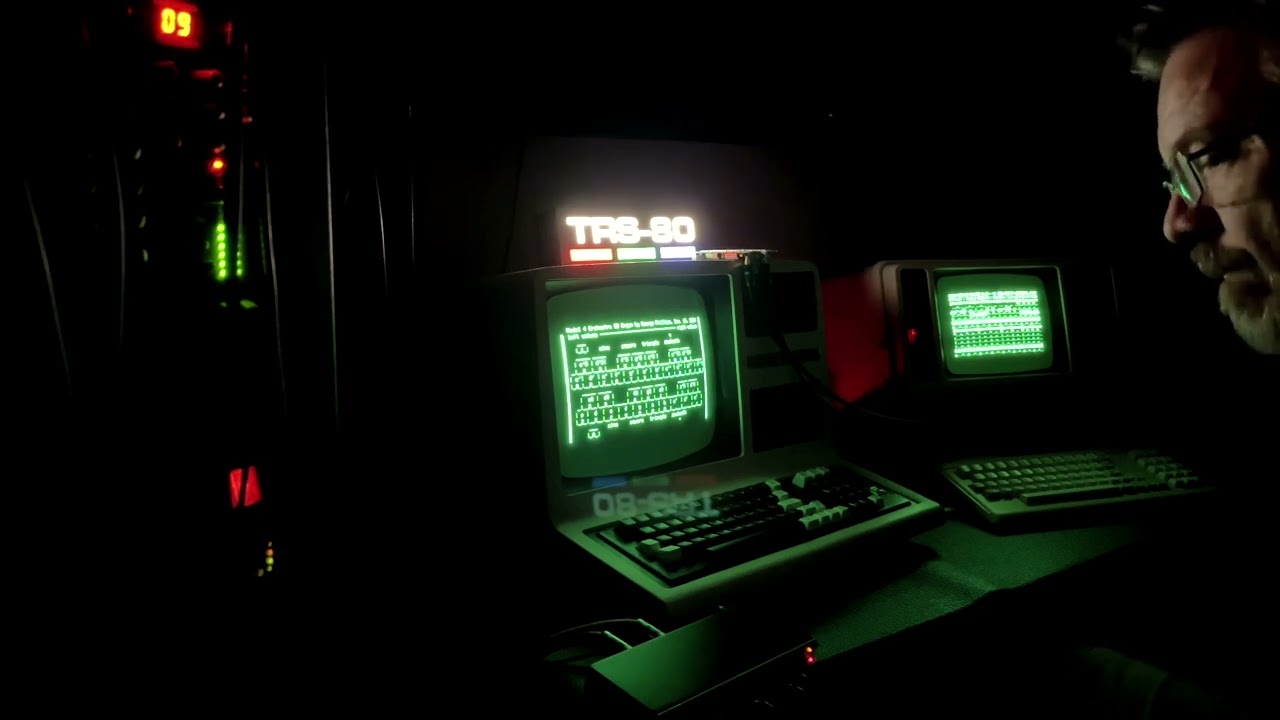

Desi and Lucy entered television in 1951, at a time when the medium was exploding in popularity. But it was still centered in New York because it was a sponsor-driven medium, unlike the movies, which were an audience-financed medium. And there was yet no coaxial cable that could enable coast-to-coast broadcasting of a live signal. So, television could appear live from New York to Omaha, certainly to Chicago, and a little bit west of the Mississippi. And then the rest of the country would have to see programming on a delayed method in which the only way to produce it was to film a program off a a video monitor, on something called a kinescope, which was not effective, partly because of the differential speed between the video image and the film. Often it was on 16mm film.

Desi and Lucy conceived “I Love Lucy” as a way to work together, rather than his being on the road with his band and Lucy making movies in Hollywood, and meeting each other at the top of Coldwater Canyon at dawn or dusk as they went to and from their various obligations. They sold the show, which CBS was reluctant to air because they thought no one would believe this inter-ethnic couple. The sponsor, Philip Morris, and the advertising executive asked when they were moving to New York. They said, “We’re not moving into New York. We want to work in Los Angeles. That’s the whole point.” So CBS said, “That’s going to cost more because you’ll have to film it.” And Desi said, “All right, we’ll take a pay cut. But in exchange, I’d like to own the negative.”

He wasn’t sure what he would do with those films, because at this point, television was a purely live medium. The notion of a rerun, that a program would be repeated, didn’t really exist. However, he knew that the program could be improved with high-quality film stock. And then the executives at CBS said, “Well, Lucy worked best with a live audience, so you have to not just film this, but you have to film it in front of a live audience.” And that led them to realize they had to film it with multiple cameras at once and film it like a little play.

A movie soundstage is a dangerous workplace, with lights, cables, fire hazards, and all kinds of other hazards. They had never had an audience in a movie. Moreover, most movies are shot with a single camera with multiple setups. And it’s incredibly boring to watch. So they came up with this notion, partly through the genius of an Academy Award-winning cinematographer named Carl Freund, who devised a system of so-called flat overhead lighting that would work for close-ups, long shots, and medium shots at the same time. They had an audience gathered on wooden metal bleachers, approximately 300 people, and filmed the whole show, more or less, live in sequence. They captured it on three cameras and then used a multi-headed editing machine to link all the footage together. Desi was right in the middle of all of that innovation, hiring the technicians who knew how to do it.

There had been some experimentation with game shows and other things, but Desi was the one who first combined all these things to film a situation comedy like a play. It quickly became the industry standard for how to do it, and it persists on sitcoms, for the most part, to this day. The result of his decision to own the negatives meant that six years later, he owned the inventory, which had become a very valuable property.

He sold them back to CBS, and that provided the nest egg that, a year later, allowed him and Lucille to buy RKO Studios and go very heavily into producing other series and programs themselves as either a landlord or a producer.

The subtitle of the book is The Man Who Invented Television, and it’s a self-conscious overstatement. But it’s a reflection of the fact that Desi did pioneer the modern business model of television, because if a program could be shown again and again, it could be sold again and again, and that has happened ever since.

And so, in a very real way, Desi was the father of the rerun, and of syndication sales, as well as the three-camera/live audience production. Again, he didn’t do this completely alone, but he was the one who took the risks and, in some critical sense, had the vision to do this at a time when others were not seeing it. The Desilu logo was featured at the end of programs like “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” “The Andy Griffith Show,” and Danny Thomas’ show, as well as other programs filmed under the Desilu method.

That brought the center of television to Los Angeles from New York. And it meant that Los Angeles would become the center of television production.

The twist to this is that just before “I Love Lucy” went on the air, the system —a coaxial cable and microwave relay—made live coast-to-coast broadcasting possible, which would have obviated the need for what they were doing. But then it would have deprived us all of having the show today, because videotape hadn’t been invented yet. If “I Love Lucy” had simply been broadcast nationwide live, we wouldn’t have a record of it. We wouldn’t have these 179 episodes that everybody has been watching until the end of time. So, it’s a remarkable intersection of technological and social change at which he exploited at precisely the right moment. And he had the foresight to know that if these things were captured, they’d be very valuable far into the future.

The letter that he wrote to Philip Morris, the show’s sponsor, is a crucial part of the book.

Before the second season, Lucy became pregnant with their second child. And there was a big controversy about what they should do because there had never been a pregnant character on television before. You couldn’t even say the word. CBS and the sponsor were very, very reluctant to have this happen. So Desi wrote a remarkable letter to the chairman of Philip Morris, Alfred Lyon, saying, “We’ve given you the number one program on television. And now your people tell us that we can’t do what we propose to do. So that’s all right. We’ll have to defer to you. But then we can no longer be responsible for the good parts of the show. And you and the advertising agency will have to, on your own, make it the number one show on television.”

Years later, he found out from the secretary to Mr. Lyon, that the chairman of the company had written a memo to everyone saying basically, “Don’t f*** with the Cuban.”

So then, because Lucy had had a cesarean section with her baby Lucy, the medical practice of that day required a second C-section.

Significantly more people watched the birth of little Ricky Ricardo on January 19th, 1953, than watched the inauguration of Eisenhower the next morning. It was a worldwide sensation. I mean, headlines all over the world were waiting for the birth of this little baby.

I love the way you wrote about one of my favorite Lucy episodes, where Lucy cannot get a moment alone with Ricky to tell him that she’s going to have a baby. You said about it what I’ve always felt: When they get to that moment on stage together, it’s not Lucy and Ricky, it’s Lucille and Desi.

No, and they had struggled. Lucy had a series of miscarriages, and they had struggled to have a baby. And she was on the cusp of 40 by the time her first baby was born, which is still considered relatively mature for a mother today. They both acknowledged later that they were overcome in speaking the lines by their own emotion at the thought that this was a real thing happening to them as real people. You can see that they kind of melt into each other. I get a little choked up because it’s such a sincere moment. Their eyes well up with tears, and their voices crack. They are both superb performers, but that’s something that no acting could convey.

Do you have a favorite Desi performance?

The one I write about in the book, when he tells Little Ricky the Little Red Riding Hood story. I found that incredibly sweet and charming. And everyone remembers the episode where Lucy and Ethel work in the chocolate factory. But they forget that in the same episode, Ricky and Fred have their own wonderful moment where they’re scrambling in the kitchen with this overflowing pot of rice. Madeline Pugh, the writer, talks about how Desi accidentally fell on the slippery rice, which they were using for the first time in the actual filming. And then, hearing the audience’s reaction, he contrived to slip on purpose by accident twice more and got two more laughs. He was a canny, canny, canny performer.

Obviously, Lucy is brilliant, and he was the first to say it, but you see the show through his eyes. He’s the one who’s rooted on the ground while Lucy’s up here. And you identify with him.

![‘Silent Hill f’ Creeps Into a September 25 Release Date; New Gameplay Trailer Revealed [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/silenthillf.jpg)

![‘Bloodstained: The Scarlet Engagement’ Announced for 2026 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/bloodstained.jpg)

![‘Mortal Kombat: Legacy Kollection’ Coming to PlayStation Later This Year [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/legacykollection.jpg)

![The Sweet Cheat [THE PAST REGAINED]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/timeregained-womanonstairs.png)

![A Depth in the Family [A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/a-history-of-violence.jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)