Escape Artist: Ted Kotcheff, 1931–2025

First Blood (Ted Kotcheff, 1982).In 1983, Ted Kotcheff attended the Brussels Film Festival as a guest of honor; he was also there to promote the first Rambo movie, First Blood (1982), which would be the biggest commercial success of his directorial career. First Blood had originally been set for production in the early 1970s but was put through the developmental wringer for the better part of a decade, with a revolving door of potential leading men, attached directors, and multiple revisions of its survival-thriller plotline. It was an odd project for Kotcheff, then best known for the barbed social satire of Fun with Dick and Jane (1977) and North Dallas Forty (1979), broad, vulgar comedies that dealt with class warfare by means other than armed combat. “Freud says that guns are an extension of your dick,” scoffs Nick Nolte’s battered wide receiver Phil Elliott in North Dallas Forty, mocking the hardened gridiron ideal he’s come to embody; when he deliberately fumbles a pass (off the field) in the final sequence, it’s as if he’s absolving himself of his own alpha-male calling, a team player striking out on his own. One wonders what Freud would have said about First Blood, a movie whose villains keep firing, indiscriminately and impotently, at an agile (and virile) moving target. It’s a superbly sculpted slab of pulp, with little of the reactionary jingoism (or action-movie gigantism) that would define its sequels. In the charming town of Hope, Washington, Sylvester Stallone’s PTSD-stricken ex–Green Beret John Rambo strains against not only the bonds of police custody but also his own fast-twitch impulses, as if he’s afraid of what might happen if he breaks free. His flight from the station via motorbike filters excitement through a misty lyricism rooted in the Pacific Northwestern setting; crouching in the forest, armed and dangerous, Rambo is both out of place and in his element, a man without a country looking for traction on home turf.The question of how a Toronto-born filmmaker came to make one of the keynote movies of the Reagan ’80s is one worth asking. In Brussels, though, Kotcheff seemed sanguine about the fact that few people seemed to notice the incongruity. Asked by an interviewer if he thought the audience knew who Ted Kotcheff was, he demurred. “I don’t think so,” he said. “And it doesn’t bother me very much.”North Dallas Forty (Ted Kotcheff, 1979). Kotcheff, who died this past April at his home in Nuevo Nayarit, Mexico, at the age of 91, did not cultivate an aura of mystery. Nor did he miss many opportunities to hold court. The director’s 2017 memoir, Director’s Cut: My Life in Film, is an example of autobiography as open book, candidly narrating its author’s picaresque trajectory from the child of Bulgarian immigrants in Toronto to a hard-driving industry pro. Kotcheff’s parents belonged to a left-wing Slavic theater group in whose plays Ted performed as a child; he was also an elementary-school violin prodigy and considered attending university for music studies (he ended up with a degree in English literature from the University of Toronto). Kotcheff’s feelings about his father were a complicated mix of admiration and fear stemming from physical abuse, but he inherited the older man’s love of movies, accompanying him to double features at repertory cinemas in and around Toronto’s Cabbagetown; his favorites were the usual suspects: Kurosawa, Hitchcock, Bergman, Welles. For work, Kotcheff punched the clock at a tire factory and a slaughterhouse (“my film school was an abattoir,” he said); in his off-hours, he nursed dreams of becoming a poet, traveling to Spain to try to cultivate his inner Hemingway. As it turned out, what he really wanted to do was direct, and at 24—encouraged by the venerable Canadian television producer Sydney Newman—began tackling episodes of the anthology series General Motors Theater (1952–61) at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).The primal scene of English-language Canadian cinema exists at the intersection of two acronymic institutions: the CBC and the NFB (National Film Board of Canada), which shared a propensity for shaping filmmakers to an in-house template rather than cultivating distinctive artistic visions. Like so many of the directors of his generation—including his friend Sidney J. Furie—Kotcheff saw the writing on the wall and headed out of town, landing in London, where he fell in with a flock of counterculture vultures with connections to film, theater, and television. He collaborated with Terry Southern and split a flat with the Montreal-born author Mordecai Richler, at that point growing into his legend as the bard of Anglo-Jewish Canadian alienation; he carved out a niche directing live television dramas, including a 1958 episode of Armchair Theatre (1956–74), “Underground,” a post-apocalyptic thriller in which a cast member suffered a fatal heart attack mid-broadcast. The legend goes that Kotcheff restructured the story during commercial bre

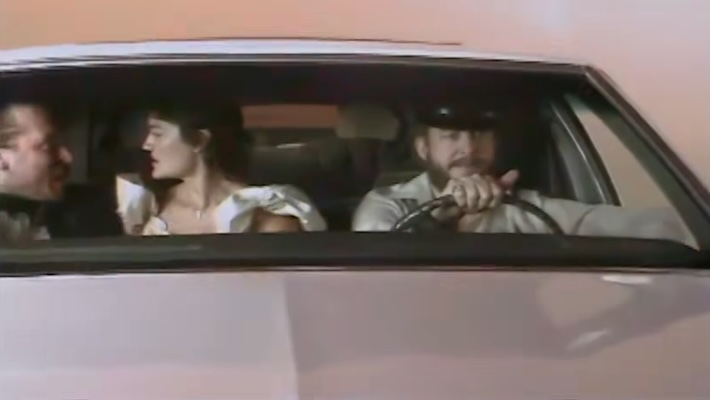

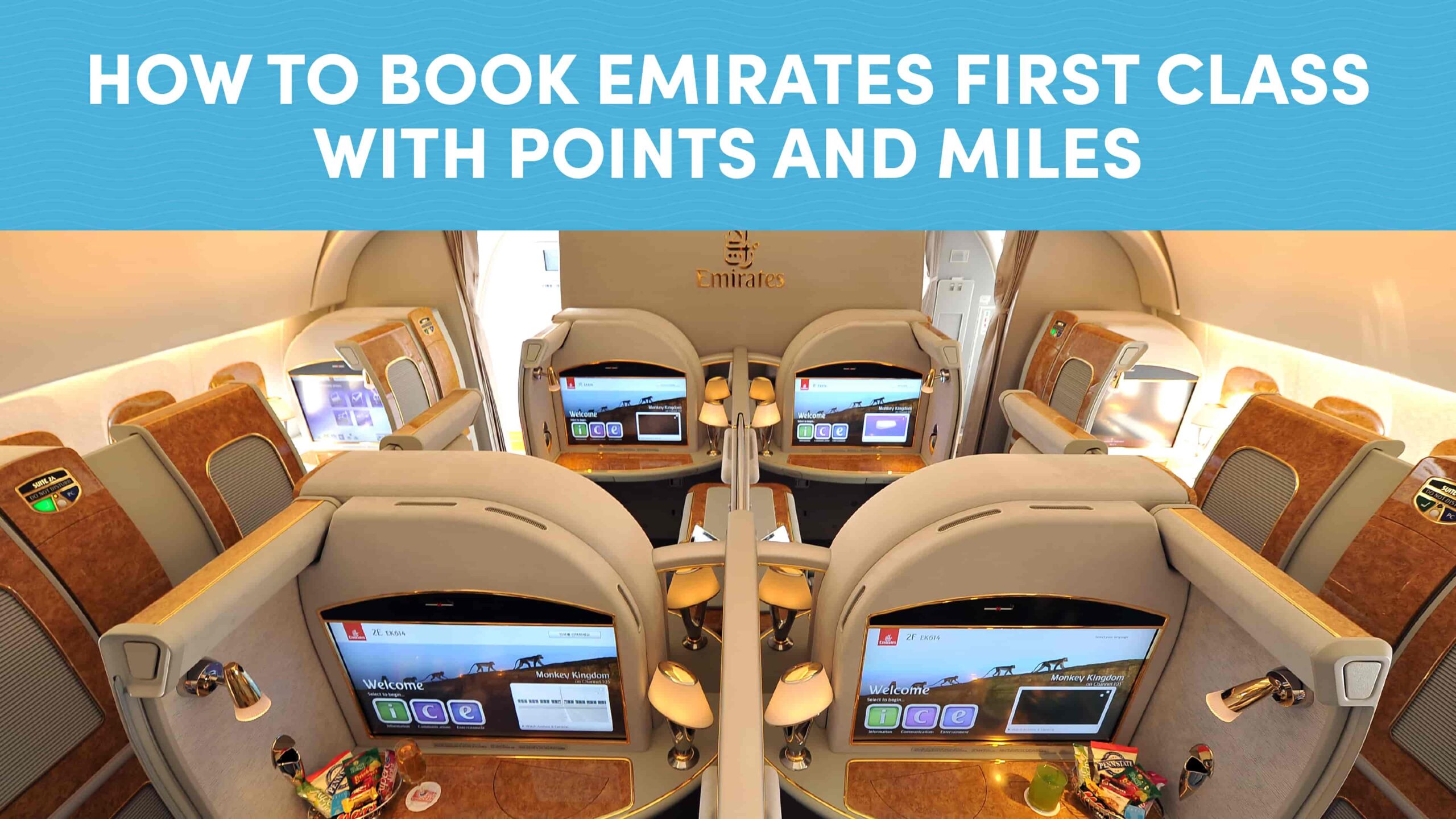

First Blood (Ted Kotcheff, 1982).

In 1983, Ted Kotcheff attended the Brussels Film Festival as a guest of honor; he was also there to promote the first Rambo movie, First Blood (1982), which would be the biggest commercial success of his directorial career. First Blood had originally been set for production in the early 1970s but was put through the developmental wringer for the better part of a decade, with a revolving door of potential leading men, attached directors, and multiple revisions of its survival-thriller plotline. It was an odd project for Kotcheff, then best known for the barbed social satire of Fun with Dick and Jane (1977) and North Dallas Forty (1979), broad, vulgar comedies that dealt with class warfare by means other than armed combat. “Freud says that guns are an extension of your dick,” scoffs Nick Nolte’s battered wide receiver Phil Elliott in North Dallas Forty, mocking the hardened gridiron ideal he’s come to embody; when he deliberately fumbles a pass (off the field) in the final sequence, it’s as if he’s absolving himself of his own alpha-male calling, a team player striking out on his own.

One wonders what Freud would have said about First Blood, a movie whose villains keep firing, indiscriminately and impotently, at an agile (and virile) moving target. It’s a superbly sculpted slab of pulp, with little of the reactionary jingoism (or action-movie gigantism) that would define its sequels. In the charming town of Hope, Washington, Sylvester Stallone’s PTSD-stricken ex–Green Beret John Rambo strains against not only the bonds of police custody but also his own fast-twitch impulses, as if he’s afraid of what might happen if he breaks free. His flight from the station via motorbike filters excitement through a misty lyricism rooted in the Pacific Northwestern setting; crouching in the forest, armed and dangerous, Rambo is both out of place and in his element, a man without a country looking for traction on home turf.

The question of how a Toronto-born filmmaker came to make one of the keynote movies of the Reagan ’80s is one worth asking. In Brussels, though, Kotcheff seemed sanguine about the fact that few people seemed to notice the incongruity. Asked by an interviewer if he thought the audience knew who Ted Kotcheff was, he demurred. “I don’t think so,” he said. “And it doesn’t bother me very much.”

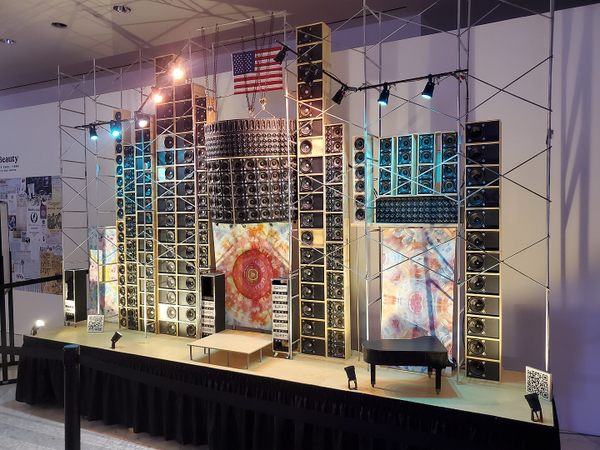

North Dallas Forty (Ted Kotcheff, 1979).

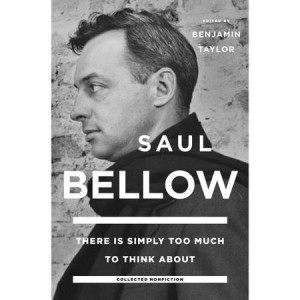

Kotcheff, who died this past April at his home in Nuevo Nayarit, Mexico, at the age of 91, did not cultivate an aura of mystery. Nor did he miss many opportunities to hold court. The director’s 2017 memoir, Director’s Cut: My Life in Film, is an example of autobiography as open book, candidly narrating its author’s picaresque trajectory from the child of Bulgarian immigrants in Toronto to a hard-driving industry pro. Kotcheff’s parents belonged to a left-wing Slavic theater group in whose plays Ted performed as a child; he was also an elementary-school violin prodigy and considered attending university for music studies (he ended up with a degree in English literature from the University of Toronto). Kotcheff’s feelings about his father were a complicated mix of admiration and fear stemming from physical abuse, but he inherited the older man’s love of movies, accompanying him to double features at repertory cinemas in and around Toronto’s Cabbagetown; his favorites were the usual suspects: Kurosawa, Hitchcock, Bergman, Welles. For work, Kotcheff punched the clock at a tire factory and a slaughterhouse (“my film school was an abattoir,” he said); in his off-hours, he nursed dreams of becoming a poet, traveling to Spain to try to cultivate his inner Hemingway. As it turned out, what he really wanted to do was direct, and at 24—encouraged by the venerable Canadian television producer Sydney Newman—began tackling episodes of the anthology series General Motors Theater (1952–61) at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

The primal scene of English-language Canadian cinema exists at the intersection of two acronymic institutions: the CBC and the NFB (National Film Board of Canada), which shared a propensity for shaping filmmakers to an in-house template rather than cultivating distinctive artistic visions. Like so many of the directors of his generation—including his friend Sidney J. Furie—Kotcheff saw the writing on the wall and headed out of town, landing in London, where he fell in with a flock of counterculture vultures with connections to film, theater, and television. He collaborated with Terry Southern and split a flat with the Montreal-born author Mordecai Richler, at that point growing into his legend as the bard of Anglo-Jewish Canadian alienation; he carved out a niche directing live television dramas, including a 1958 episode of Armchair Theatre (1956–74), “Underground,” a post-apocalyptic thriller in which a cast member suffered a fatal heart attack mid-broadcast. The legend goes that Kotcheff restructured the story during commercial breaks, switching the show’s visual style to a roaming kind of verité to capture the cast’s shell-shocked—but ultimately successful—improvisations.

Director’s Cut is loaded with such wild, show-must-go-on tales, shot through with nostalgia for the author’s youthful hell-raiser days. In his early twenties, Kotcheff was barred from entering the United States for suspected Communist activities and sympathies (he had been part of a left-wing book club); the incident slowed his movement toward Hollywood. Ditto his gig in 1968 shooting an anti-apartheid charity event at Royal Albert Hall in London, during which the rock band Nice burned a cardboard image of the American flag. Describing Canada’s venerable Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Kotcheff maps his homeland’s complicitous inferiority complex: “They put Vaseline on their posteriors, to make it easier for the Yanks to bone them.” Elsewhere, Kotcheff dishes on A-list collaborators from Ingrid Bergman and David Niven to Jane Fonda and Sylvester Stallone, claims to have been offered A Clockwork Orange (1971) before Stanley Kubrick, and recalls shop talk with Michelangelo Antonioni, who supposedly admired Kotcheff’s sophomore feature, Life at the Top (1965), and wanted input into how to best streamline Blow-Up (1966).

The idea of a creative summit between the directors of Red Desert (1964) and Weekend at Bernie’s (1989) suggests a sort of bizarro film-cultural thought experiment: the auteur taking notes from the journeyman. “You could attempt to trace a throughline in [Kotcheff’s] oeuvre,” writes The Current’s David Hudson, “but you might as well be herding cats”; in his 2022 video essay on Kotcheff’s filmography, “Looking to Get Out,” critic and author Daniel Kremer choreographs the felines in question with a deft touch. Gently contradicting his subject’s own assessment in Director’s Cut about his auteurist bona fides—namely, that he doesn’t have any—Kremer makes the case for a common denominator between Kotcheff’s films: their consistent, compulsive focus on hard-luck (and/or willfully self-destructive) protagonists bridling against their immediate circumstances. For Kremer, Kotcheff’s characters are all “looking to get out,” a roll call that includes the hapless traveler in Wake in Fright (1971); the pent-up young cultist of Split Image (1982); the aforementioned Phil Elliott in North Dallas Forty, and yes, John Rambo, a discarded veteran fighting for a life he doesn’t seem all that invested in continuing. Noting proudly that only one character actually dies on screen in First Blood, Kotcheff refused to do the sequel on the grounds that that the material was veering into (literal) overkill.

Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971).

Released at the outset of the Australian New Wave, Wake in Fright is Kotcheff’s consensus masterpiece—a grim thriller set in the fictional New South Wales hamlet of Bundanyabba. Its story of a meek (if narcissistic) city mouse stranded in the deep, dark country slots between—and compellingly synthesizes elements of—Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971)and John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972). The film is simultaneously hallucinatory and rough-hewn, rendering the Outback as a Boschian garden of earthly delights. “All the little devils are proud of Hell,” crows Clarence “Doc” Tyson (Donald Pleasance), the alcoholic doctor who styles himself as a one-man welcome party for Gary Bond’s wayward schoolteacher, John Grant. John is en route to the gleaming promised land of Sydney, but finds himself unable to extricate himself from the Yabba—possibly because, subconsciously, he’s drawn to its brutal rituals, including gambling, brawling, and psychosexual gamesmanship that leaves him questioning every aspect of his identity. The film’s centerpiece is a brutal kangaroo hunt cobbled together using documentary footage gleaned while riding shotgun with real-life poachers. (Certain images of slaughtered kangaroos in Wake in Fright were authentic; “repellent as some of the footage was that I obtained and used in my film, it was the least upsetting of what I shot,” writes Kotcheff in a note for the film’s restoration in 2009.) “Did you have a good holiday?” queries one beer-swilling local as John—recovered from a stress-induced suicide attempt and restored to his natty old self—catches a train out of town; “the best,” he replies in a way that suggests, ruefully and perversely, he means it, a conflicted little devil on his way out of Hell.

Where Wake in Fright hunkers down in fraught physical and psychological terrain, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974) treats the darkness of the soul with a light touch. Skillfully adapted by Lionel Chetwynd from Richler’s influential bestseller, the film offers an exultant portrait of the (con) artist as a young man, conveyed via Richard Dreyfuss’s extraordinary performance, perched on the fault line between hatefulness and ingratiation. Introduced not-so-discreetly inflating a condom during a marching-band parade down Montreal’s Saint Urbain Street, Duddy serves dually as a stand-in for Richler and for Kotcheff, who draws out the character’s furious, barely sublimated self-loathing, and his gut-deep anxieties over the wandering-Jewish birthright he uses to justify some distinctly secular (and very savvy) avarice. Duddy’s contempt for the high rollers he serves while working at a luxury resort is real, but also aspirational; when he stumbles upon a beautiful, unblemished lakefront in the Laurentians, he instantly imagines himself “the king of the mountain,” and proceeds to mortgage his soul (and whatever else he can get his hands on) to ascend to the throne.

The metaphysics of such hustling schmuckery are plenty familiar (Richler bows to Philip Roth as the king of this particular mountain) but The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz is so swift and funny that it particularizes its pilgrim’s progress; nearly every scene has some off-kilter line reading or winningly grotty little detail. Best in show is the subplot about a blacklisted, cash-strapped British filmmaker, Peter John Friar (a riotous Denholm Elliott), who claims persecution simultaneously by the Deep State and the showbiz industrial complex (“Eton and Cambridge are no good to me in Hollywood”) and has been reduced to reconfiguring the bougie bar mitzvahs he films into pompous mock-ethnography, intercutting African tribal rituals with Torah readings. Although faithfully translated word for word from the novel, Elliott’s scenes play like a gentle shiv to the ribs of Kotcheff’s own UK apprenticeship; with apologies to A Serious Man (2009), Friar’s magnum opus, “Happy Bar Mitzvah, Bernie,” remains the funniest depiction of Jewish coming-of-age ever put on screen. (“Cost plenty, don’t worry, it’s all paid for,” grumbles Bernie’s scrap-merchant dad as the lights go up.)

Top: The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (Ted Kotcheff, 1974). Bottom: Joshua Then and Now (1985).

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz won the Golden Bear in Berlin and a handful of Canadian film prizes; Kotcheff would return to Richler’s universe in Joshua Then and Now (1985), a thematic companion piece to Duddy Kravitz with a fussier, flashback-driven structure and a sour, pervasive sense of compromise. As its title suggests, it’s about a man—a successful writer styled again as a surrogate for Richler—sorting through the fragments of his life, most of which are jagged enough to draw blood. (Here, there’s no way out, just a deeper immersion in memory.) Beyond the positively chameleonic lead performance by James Woods—coming off his collaboration with another Toronto director, David Cronenberg, in Videodrome (1983)—Joshua Then and Now is mostly notable for being produced simultaneously as a theatrical feature and a television miniseries, an attempt by fledgling producer Robert Lantos to maximize the project’s government funding. “I never should have done it that way because you can't shoot two films at once, and a miniseries is different from a film,” Kotcheff told Paul Rowlands in 2017. “Because of that, I have always been dubious about the quality of the movie.”

And there’s the rub. If Kotcheff’s overall reputation is less than stellar, it’s because, subtextual throughlines aside, a good percentage of his filmography is considered mediocre or worse. Exhibit A: Weekend at Bernie’s (1989),his only real commercial hit after First Blood and a critical punching bag that’s better than its reputation, shot through with many of the same themes of class anxiety, hustle, and ingenuity as Kotcheff’s ’70s comedies, albeit drenched in a sort of Day-Glo cynicism. Its protagonists are a pair of naïvely unscrupulous finance bros—Wall Street cousins to Duddy Kravitz played in a wonderfully feckless double act by Andrew McCarthy and Jonathan Silverman—desperate to move out of their roach-infested Manhattan apartments (“they scatter when the lights come on”) and make some real money. Their meal ticket: the corpse of their Gordon Gekko manqué boss, Bernie (Terry Kiser), a fraudster and mob associate who got what was coming to him and now serves nicely as a combination marionette / human shield / slowly moldering all-access pass into a world of wealth and privilege. The very definition of a one-joke movie—with the caveat that it keeps wringing inventive variations on that joke, which is that a stiff like Bernie is more fun dead than alive—Weekend at Bernie’s is tactless, tasteless, and consistently funny, deploying sight gags with assembly-line timing and precision. Kremer smartly cites Blake Edwards as a precedent; Antonioni, whose own depictions of privileged and insular rituals were shaded with a degree of necrophilia, might have appreciated his old friend’s film as a come-dressed-as-the-sick-soul-of-the-Hamptons costume party.

Kotcheff only made three more movies after Weekend At Bernie’s; as with First Blood, he torpedoed his own professional prospects by declining to do a sequel. His swan song was The Shooter (aka Hidden Assassin, 1995), starring Dolph Lundgren, dismissed upon release by Variety as an “international action pudding whose dough consistently refuses to rise.” In actuality, Shooter is a solid, weirdly moody little thriller (complete with allusions to Hamlet) that uses its post-glasnost Eastern European locations and context evocatively (Lundgren’s character is a refugee of the Prague Spring, and wears his status as a US Marshal with a bit of ambivalence). The emphasis on brutal, close-quarters combat (and a plotline defined by shifting, contingent sympathies) makes The Shooter a fine complement to First Blood, and not only because it casts Ivan Drago as a sullen, world-weary hero. The last shot of Lundgren’s battered, broken-hearted Michael Dane works, however indirectly, as a bookend to Stallone’s introduction as John Rambo, and a surprisingly apt emblem for Kotcheff himself. He’s walking away from the camera, alone, on his own terms.

![Watch: American Airlines Passengers Casually Walk Aisles During Taxi—Did Seatbelt Rules Just Disappear? [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/standing-in-aisle.jpg?#)

![This Switch 2 Accessory Is Making Fans Drop Their Consoles And The Manufacturer's Response Is Only Making Things Worse [Update: Everyone's Getting Free Upgraded Joy-Con Grips Following Death Threats]](https://i.kinja-img.com/image/upload/c_fill,h_675,pg_1,q_80,w_1200/d26954494c474d4929b602da22e51149.gif)

![[Podcast] Problem Framing: Rewire How You Think, Create, and Lead with Rory Sutherland](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/rort-sutherland-35.png)