The Best Films of 2025 (So Far)

As we approach 2025’s halfway point it’s time to take a temperature of the finest cinema thus far: we’ve rounded up our favorites from the first six months of this year, some of which have flown under the radar. Kindly note that this is based solely on U.S. theatrical and digital releases from 2025. Check […] The post The Best Films of 2025 (So Far) first appeared on The Film Stage.

As we approach 2025’s halfway point it’s time to take a temperature of the finest cinema thus far: we’ve rounded up our favorites from the first six months of this year, some of which have flown under the radar. Kindly note that this is based solely on U.S. theatrical and digital releases from 2025.

Check out our picks below, as organized alphabetically, followed by honorable mentions.

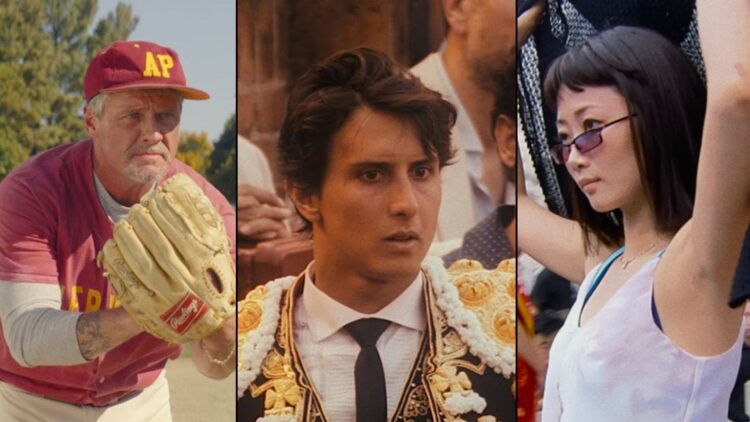

Afternoons of Solitude (Albert Serra)

Albert Serra’s new film Afternoons of Solitude is more akin to two hours of Sky Sports than you’d expect from the guy who once made Story of My Death. Following the rules, if not the spirit, of ever-festival-fashionable observational and direct cinema, we spend most of its runtime in long takes observing Spanish bullfighting rings, our eyes focused on Andrés Roca Rey, a Peruvian “exemplar” of the sport engaged in utmost, ritualized savagery. We’re very sensitized to the constructed and artificial nature of documentary now, but Serra’s prime achievement here is to achieve an objectivity of perspective. Commanded by DP Arthur Tort, it’s not a leering camera, and the editing patterns don’t cut to close-ups coercing us into disapproval, to achieve a a rapport where we can agree “this is awful, isn’t it.” It suggests an anthropological record of a pastime deserving our deference and grudging respect, yet equally an indictment of something barbaric and finally absurd. Roca, shown in power stance with his eyes focused and vulnerable like the poor bull’s, seems both hero and villain of the piece, but those categories also fail to apply here. Framed sculpturally and monumentally, as a body in cinematic space, he merely is. – David K. (full review)

April (Dea Kulumbegashvili)

Like Beginning, April also carries the mark of reality, mediated. The director is inspired by fictionalized stories gleaned from the real world––especially her hometown, a village at the foot of the Caucasus mountains in Georgia and its people. Beginning’s sparse dialogue, long takes, and atmosphere of violence closing in on the main character––a Jehovah Witnesses pastor’s wife played by the new film’s lead, Ia Sukhitashvili––made space thicken and swell, while April breathes. Arseni Khachaturan’s patient, somehow insistent camera uncovers a world that is both familiar and uncanny: a world split between rumbling storms, rainfall, a gorgeous sunset seen from angles almost as low as the grass itself, and a rotting patriarchal society that squashes female independence with its body politics. Nina (Sukhitashvili) is an OBGYN who, despite best efforts, has to report a newborn’s death as the result of a previously unregistered pregnancy. The local woman’s husband demands an investigation, well aware of rumors that Nina performs illegal abortions in the village––something the patriarchy cannot allow. – Savina P. (full review)

Black Bag (Steven Soderbergh)

If a James Bond or Mission: Impossible film excised all its action scenes––save a stray explosion or gunshot––while employing a script with a pop John le Carré sensibility, it might resemble something like Steven Soderbergh’s Black Bag. A hyper-slick, suave spy thriller, it’s mainly relegated to dinner tables and office rooms as stages for rapid-fire, gleefully barbed verbal sparring scripted by David Koepp, returning to the genre after Ethan Hunt’s first outing. Primarily focusing on a trio of couples working in British intelligence, Koepp’s script poses the question: it is possible to have a healthy relationship when there’s no such thing as separating work from life, particularly when your job description is one of a professional liar? – Jordan R. (full review)

Broken Rage (Takeshi Kitano)

Split into two chapters, the film kicks off as a crime thriller before switching tones altogether and revisiting the first part scene-by-scene in a more delirious light. Kitano stars in both as a gun-for-hire. Infallible in the first and hopelessly clumsy in the second, he’s “Mouse,” a hit man whose murderous routine is upended once cops recruit him to infiltrate a drug ring. Tonally distinct as they may be, humor permeates both parts. Even in the ostensibly more “serious” first, Kitano’s script moves with a childlike logic: it only takes Mouse a couple of punches in a staged brawl with another mole to ingratiate himself with the mobsters he’s been asked to spy on. His killing-machine loner is a comic riff on the other unbeatable assassins he played in the past (think of Otomo, the thug of his Outrage saga). But the commitment to poking fun at his onscreen personas is something I hadn’t seen him do since 2005’s Takeshis’, a comedy that nonetheless spiraled into self-indulgent flights of fancy. Nothing farther from Broken Rage’s spirit. This isn’t just a wildly funny film––the kind that sent people around me at the press premiere into convulsed laughter just a few scenes in––but a pointed rebuke to the discourse that saw the director’s two impulses (popular comedy and artful seriousness) as opposite poles in a magnetic field. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Caught by the Tides (Jia Zhangke)

Jia Zhangke’s is often a cinema of déjà vu: “We’re again in the northern Chinese city of Datong,” Giovanni Marchini Camia wrote for Sight and Sound back in 2019, “it’s again the start of the new millennium, Qiao is again dating a mobster, yet no one else makes a reappearance and there are enough differences to signal that this isn’t a sequel or remake.” Camia was writing about Ash Is Purest White yet much of the same could be said for Caught by the Tides, the director’s latest experiment in plundering his archive––indeed his memories––and spinning what he finds into something new. The protagonist of Tides is again named Qiao and is again played by Zhao Tao, appearing here in more than 20 years of the director’s footage and allowing the viewer to watch that singular creative partnership evolve in real time––one of the great treasures of contemporary cinema. – Rory O. (full review)

Eephus (Carson Lund)

If the perfect sports movie illuminates the fundamentals that make one fall in love with the game, there may be no better movie about baseball than Carson Lund’s Eephus. Structured solely around a single round of America’s national pastime, Lund’s debut feature beautifully, humorously articulates the particular nuances, rhythms, and details of an amateur men’s league game. By subverting tropes of the standard sports movie––which often captures peak physical performance in front of legions of adoring fans––Lund has crafted something far more singularly compelling. Rather than grand slams and no-hitters, there are errors aplenty and no shortage of beer guts and weathered muscles amongst the motley crew. Lund is more interested in examining the peculiar set of social codes that only apply when one is on the field, unimpeded by life’s responsibilities and entirely focused on the rules of the game. – Jordan R. (full review)

The Encampments ( Michael T. Workman and Kei Pritsker)

A group of students, primarily led by minority voices, launched encampments in protest of Columbia University’s financial ties to companies with the express purpose of advancing weapons and technology to fuel the war machine. Police were called in to forcefully squash the protests. The activism and those involved opened the eyes of the nation and globe, advancing critical thinking and free thought in the name of progress. The year is 1968. Over half a century later is history repeating itself, but this time with more assertive opposition, distortion of facts, and willful ignorance of the suffering on the part of those in power. – Jordan R. (full review)

Familiar Touch (Sarah Friedland)

In a sunny kitchen in California, Ruth prepares a sandwich with the muscle memory that only a lifetime allows. Bread is toasted and left to cool; dill is picked and chopped efficiently; sour cream, radish, and salmon are arranged to resemble a blooming flower. After going to get ready, she serves it to a man named Steve (H. Jon Benjamin) who she doesn’t seem to recognize. When he tells her he’s an architect, she responds, “My father builds homes. Maybe you’ll meet him one day.” Caught off-guard, her son can only offer a loving smile and say “I’d like that.” This uncertain space––part clarity, part blur––is the subject of Sarah Friedland’s moving debut feature Familiar Touch. – Rory O. (full review)

The Fishing Place (Rob Tregenza)

Rob Tregenza’s first film in nearly a decade suggests no diminishment in power or vision; if anything The Fishing Place embodies the dual influence of pent-up energies and careful refinement. On the surface a tale of faith and espionage in rural Norway circa World War II––snowy landscapes, candlelit rooms, and the cold, cold light of day shining through church windows––the film hums with secret histories and spiritual tension, culminating in both long-take assassinations and a beguiling denouement that yanks the film from its ‘40s trappings and emulates Taste of Cherry. One hopes it isn’t the 74-year-old filmmaker’s final statement, but as such it would properly close a sui genesis career in American cinema. – Nick N.

Friendship (Andrew DeYoung)

The level of enjoyment audience members will have with Andrew DeYoung’s Friendship is tied directly to their tolerance for the humor of Tim Robinson. The star of the meme-inspiring Netflix series I Think You Should Leave has cultivated a devoted following by creating situations of embarrassment and characters who veer wildly from absurdist rage to complete self-delusion. (See the infamous “we’re all trying to find the guy who did this” meme.) In my mind, I Think You Should Leave is the funniest series of the last decade or so. While Robinson’s full-length feature as star does not reach his show’s highs, it’s still a hysterically funny, pitch-black comedy. – Christopher S. (full review)

Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes)

If Chris Marker and Preston Sturges ever made a film together, it might have looked something like Grand Tour, a sweeping tale that moves from Rangoon to Manila, via Bangkok, Saigon and Osaka, as it weaves the stories of two disparate lovers towards a fateful reunion. The stowaways could scarcely be more Sturgian: he the urbane man on the run, she the intrepid woman trying to track him down. Their scenes are set in 1917 and shot in a classical studio style, yet they’re delivered within a contemporary travelogue––as if we are not only following their epic romance but a director’s own wanderings. – Rory O. (full review)

Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath)

One of the most thought-provoking, densely assembled documentaries of the year is opening this week at Anthology Film Archives. Alexander Horwath’s Henry Fonda for President, which premiered at Berlinale last year, is a three-hour journey through the career of the legendary actor. But rather than telling a standard cradle-to-grave story, performances and life events are used to chart a course of the history of America itself. Also featuring audio from Fonda’s final interview, it’s a truly fascinating approach to rethinking the biographical documentary. – Jordan R.

Misericordia (Alain Guiraudie)

In a career spanning four decades and eight features, Alain Guiraudie has cemented himself as one of our most astute chroniclers of desire. If there’s any leitmotif to his libidinous body of work, that’s not homosexuality (prevalent as same-sex encounters might be across his films) but a force that transcends all manner of labels and categories. His is a cinema of liberty: of vast, enchanted spaces and solitary wanderers who wrestle with their passions, and in acting them out, change the way they carry themselves into the world. Desire becomes an exercise in self-sovereignty, a way of reasserting one’s independence––a rebirth. It is often said that cinema is an inescapably scopophilic realm, where the act of looking is itself a source of pleasure, but Guiraudie has a way of making that dynamic feel egalitarian, as thrilling for those watching as it is for those being watched. – Leo G. (full review)

Pavements (Alex Ross Perry)

If the Hollywood superhero-industrial complex is perishing, the Rolling Stone and Spin magazine extended universe is hastily being built. What better defines “pre-awareness” for the studios like the data logged by Spotify’s algorithm, where billions of track plays confirm what past popular music has stood the test of time, and also how––in the streaming era––you can gouge ancillary money from it? But unlike the still-brilliant Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, which stood to excoriate the nostalgia sought by such films, recently reinvigorated by the success of Bohemian Rhapsody, Alex Ross Perry’s Pavements, on the eponymous ’90s slacker idols, justifies that every great band deserves a film portrait helping us to wistfully remember them, and also chuckle as pretty young actors attempt to nail the mannerisms of weathered, road-bitten musicians. So good luck, Timothée. – David K. (full review)

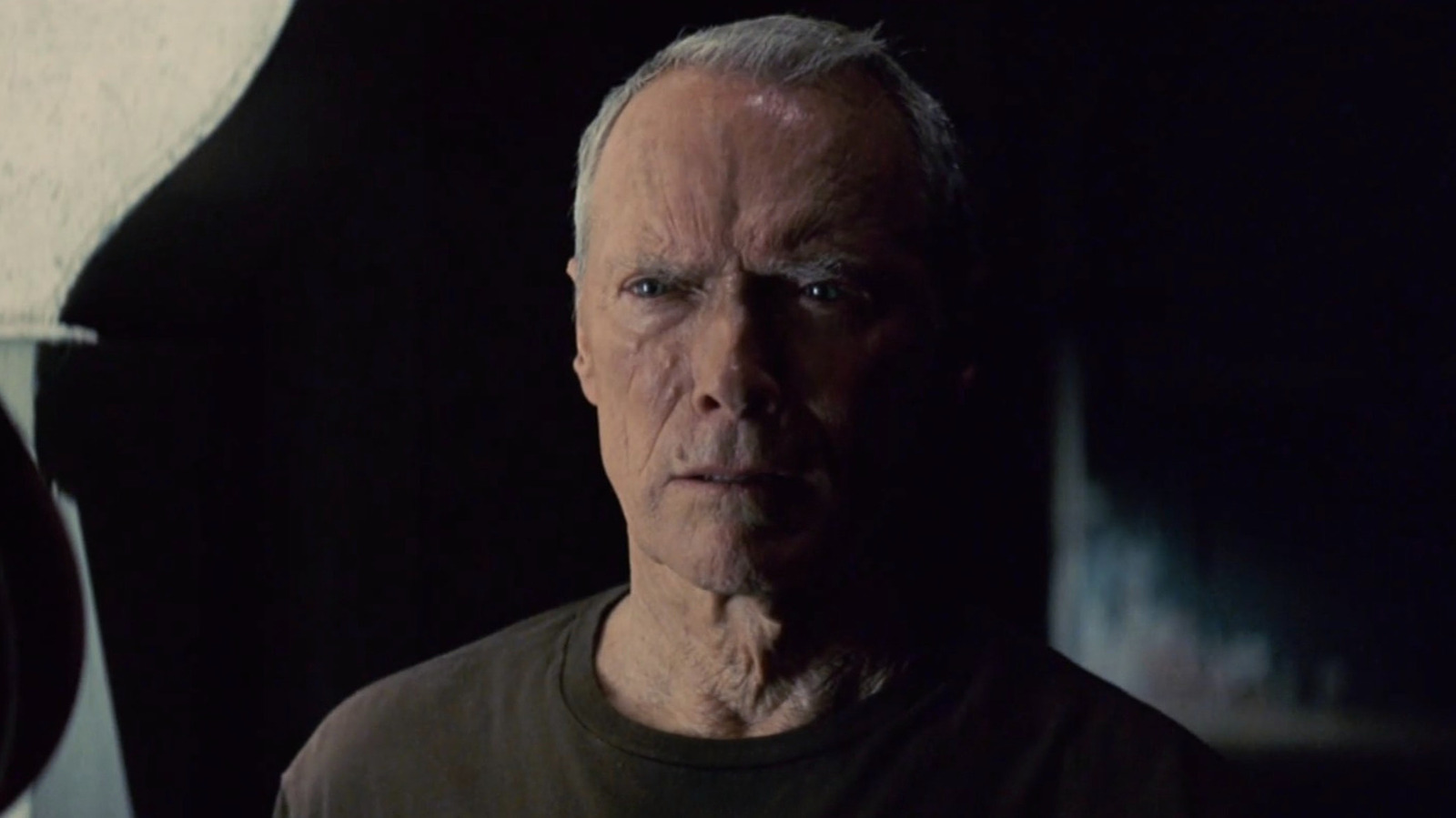

The Shrouds (David Cronenberg)

David Cronenberg, who recently celebrated his 82nd birthday, has only grown sharper and more devastating in reckonings with the body. After his long-awaited return with Crimes of the Future, Cronenberg quickly followed it up with The Shrouds, a darkly funny, mournful conspiracy thriller led by Vincent Cassel, Diane Kruger, and newly minted Oscar nominee Guy Pearce. Rory O’Connor said in his Cannes review, “David Cronenberg’s films have often imagined a future where technology would find a way into our collective id. 55 years into the director’s incomparable career, might that future have finally caught up with him? In Cronenberg’s new film––the slick, scrambled The Shrouds––there are two barely speculative conceits: that an AI chatbot could be designed to look like a recently deceased love one; and primarily, that a company might have the bright idea to wrap a blanket of HD cameras around our nearest and dearest before they’re sent six-feet-under, allowing us to check in on their decaying corpse, all with the click of an app.”

Sorry, Baby (Eva Victor)

Agnes’ (Eva Victor) life is defined by a sense of stagnancy. Four years after completing grad school in rural New England, she’s living in the same house and going to the same building, only now as a professor. Whatever true joy she seems to experience is infrequent visits from her best friend and former roommate Lydie (Naomi Ackie), who has moved on, starting a family in New York City. As Victor assiduously peels back the layers of her sharp, unnerving, witty feature debut Sorry, Baby, the reason for being stuck in time becomes clear: in her final days of grad school she was raped by her advisor, who quickly deserted the town, leaving no culpability and even less sense of justice or closure. – Jordan R. (full review)

Sinners (Ryan Coogler)

Yet Sinners mainly feels so refreshing when this richness of text can easily be overlooked for enjoyment of an unholy hybrid of period drama and horror freakout, Coogler showing as much reverence for the genre as he does the centuries of music which guide this story (and Ludwig Göransson’s excellent score). Most importantly, he remembers that the archetypal vampire tale is an inherently horny one, and he pulls some tricks from Luca Guadagnino’s book for making sexually explicit stories which play even more erotically from what they withhold. Every sex scene features fully clothed actors, but all contain dialogue, or specific kinky details, which serve to remind us that, Dracula onwards, the best vampire stories are carnal ones where characters’ lust is baked into the premise. – Alistair R. (full review)

Việt and Nam (Trương Minh Quý)

The opening shot of Việt and Nam, writer-director Trương Minh Quý’s sophomore film, is a feat of cinematic restraint. Nearly imperceivable white specs of dust begin to appear, few and far between, drifting from the top of a pitch-black screen to the bottom, where the faintest trace of something can be made out in the swallowing darkness. The sound design is cavernous and close, heaving with breath and trickling with the noise of running water. A boy incrementally appears, walking gradually from one corner of the screen to the other. He has another boy on his back. A dream is gently relayed in voiceover. Then, without the frame ever having truly revealed itself, it’s gone. – Luke H. (full review)

Vulcanizadora (Joel Potrykus)

Like the punk-rock cousin of Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, Joel Potrykus’ Vulcanizadora also concerns a voyage in the woods that pinpoints the exact moment an old friendship abruptly dies. The film also represents a maturing-of-sorts for the Michigan-based provocateur, revisiting characters first introduced in his 2014 film Buzzard and a few themes explored in his lesser-known 2016 feature The Alchemist Cookbook. Like many artists shifting from early to mid-career, Potrykus explores themes of having a family––or, in this case, abandoning it––while still retaining the edge present in his nascent works. It suggests a conundrum of sorts, but while other indie filmmakers start small and work towards scaling-up, this filmmaker refreshingly hasn’t. (His 2018 masterpiece Relaxer took place in the corner of an apartment, rather than expanding his slacker universe). – John F. (full review)

Who by Fire (Philippe Lesage)

After his revelatory coming-of-age film Genesis, Quebecois filmmaker Philippe Lesage has expanded his canvas with Who by Fire, a lush, intimate, psychologically riveting drama following two families on a secluded getaway in a remote cabin as they contend with career and romantic jealousies. David Katz said in his Berlinale review, “It’s a truly unrequited, anti-love triangle, and like in his previous work, Lesage sensitively reflects on but never sentimentalizes adolescent behavior: what we observe is raw, tentative, sometimes inexplicable, and put before us as if in a clinical setting, under laboratory conditions and stark lights.”

Honorable Mentions

- 28 Years Later

- 7 Walks with Mark Brown

- The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire

- Bring Her Back

- Dangerous Animals

- Deaf President Now!

- Den of Thieves 2: Pantera

- Direct Action

- The Heirloom

- In the Lost Lands

- Invention

- Love and Sex

- Pepe

- Presence

- Milisuthando

- Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning

- One to One: John & Yoko

- On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

- The Phoenician Scheme

- Secret Mall Apartment

- Sister Midnight

- Tendaberry

- The Ugly Stepsister

- You Burn Me

The post The Best Films of 2025 (So Far) first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Watch: American Airlines Passengers Casually Walk Aisles During Taxi—Did Seatbelt Rules Just Disappear? [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/standing-in-aisle.jpg?#)

![This Switch 2 Accessory Is Making Fans Drop Their Consoles And The Manufacturer's Response Is Only Making Things Worse [Update: Everyone's Getting Free Upgraded Joy-Con Grips Following Death Threats]](https://i.kinja-img.com/image/upload/c_fill,h_675,pg_1,q_80,w_1200/d26954494c474d4929b602da22e51149.gif)

![[Podcast] Problem Framing: Rewire How You Think, Create, and Lead with Rory Sutherland](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/rort-sutherland-35.png)