GUIDE PARKETT: parliamo di Footwork (vol. I)

In un panorama musicale elettronico ricco di sottogeneri che si intersecano continuamente tra loro, Parkett ha deciso di fare un po’ di chiarezza. Questa nuova rubrica non è pensata per dettare legge: l’obiettivo è fare ricerca, interpellare, instaurare un dialogo aperto tra chi fa musica e chi l’ascolta. PREAMBOLO – Drum and bass? – We […]

In un panorama musicale elettronico ricco di sottogeneri che si intersecano continuamente tra loro, Parkett ha deciso di fare un po’ di chiarezza. Questa nuova rubrica non è pensata per dettare legge: l’obiettivo è fare ricerca, interpellare, instaurare un dialogo aperto tra chi fa musica e chi l’ascolta.

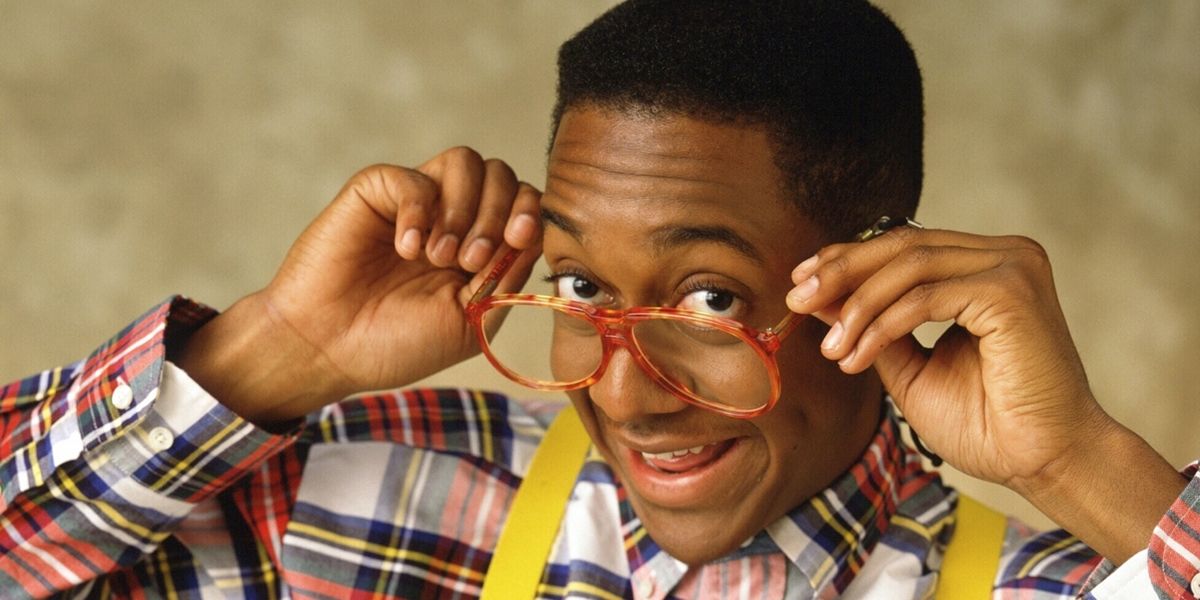

– We can’t accept drum and bass, we need jungle, I’m afraid.

Citazione a parte (se non l’avete già capita, QUI la reference), quante volte vi è successo, nel catalogare anche solo mentalmente un brano, di dubitare sul genere o forse più spesso sul sottogenere o stile di quest’ultimo? O quante persone riconducono tutta la musica elettronica ad un semplice “Sì dai, mi piace la techno“?

La prima distinzione da fare è ovviamente quella tra tipi di ascolto. La realtà è che ci sono due tipi principali di ascoltatori: quelli che ascoltano un pezzo senza farsi particolari domande rispetto al tipo di musica che stanno ascoltando… e quelli che invece lo fanno. Ogni forma di ascolto è personale e unica e riteniamo che debba essere libera da qualsiasi forma di giudizio. Tuttavia, questa rubrica è nata con lo scopo di creare un dialogo aperto con il secondo gruppo sopracitato, che molto spesso si trova a dubitare tra due o più stili di musica elettronica ai quali ricondurre qualcosa che sta ascoltando. A chi invece questo dubbio non sorge mai: i nostri più sinceri complimenti.

È anche vero che alcuni brani – e ci concentriamo qui solo sulla musica elettronica – sono incatalogabili, o comunque difficili da incasellare in un solo scompartimento. In mezzo a tutta questa (bellissima) commistione musicale, è però da riconoscere che tempi, ritmi e strumenti si riconducono di più a certi stili piuttosto che ad altri. Il proposito di Parkett è proprio quello di dare uno strumento in più per addentrarsi in questa divisione e poter distinguere quali sono queste caratteristiche principali. Questa nuova rubrica non è pensata per dettare legge: l’obiettivo è fare ricerca, interpellare e, perché no, instaurare un dialogo aperto tra chi fa musica e chi l’ascolta. Perciò facciamo polemica se ce n’è bisogno, ma che sia buona polemica. Buona lettura!

FOOTWORK

Questo stile musicale ha avuto un enorme successo negli ultimi quindici anni, ma in realtà nasce come qualcosa di profondamente underground, che si limitava, perlomeno in un primo momento, a dei luoghi e gruppi di persone ristretti.

Per parlare dell’origine del footwork dobbiamo spostarci a Chicago e tornare indietro fino agli anni ’90. In questo periodo c’è un grande fermento per le strade della città, dall’house si è generata la ghetto house, chiamata anche booty house in una sua variante più energica, con drums più forti e vocals molto spesso rappati e dal contenuto sessualmente esplicito. Parliamo ancora di 120-130 bpm. Di seguito un esempio pratico di quello che era la ghetto o booty house, in uno dei mixtapes più emblematici del tempo proveniente dalla mano di DJ Funk, uno dei pioneri del genere:

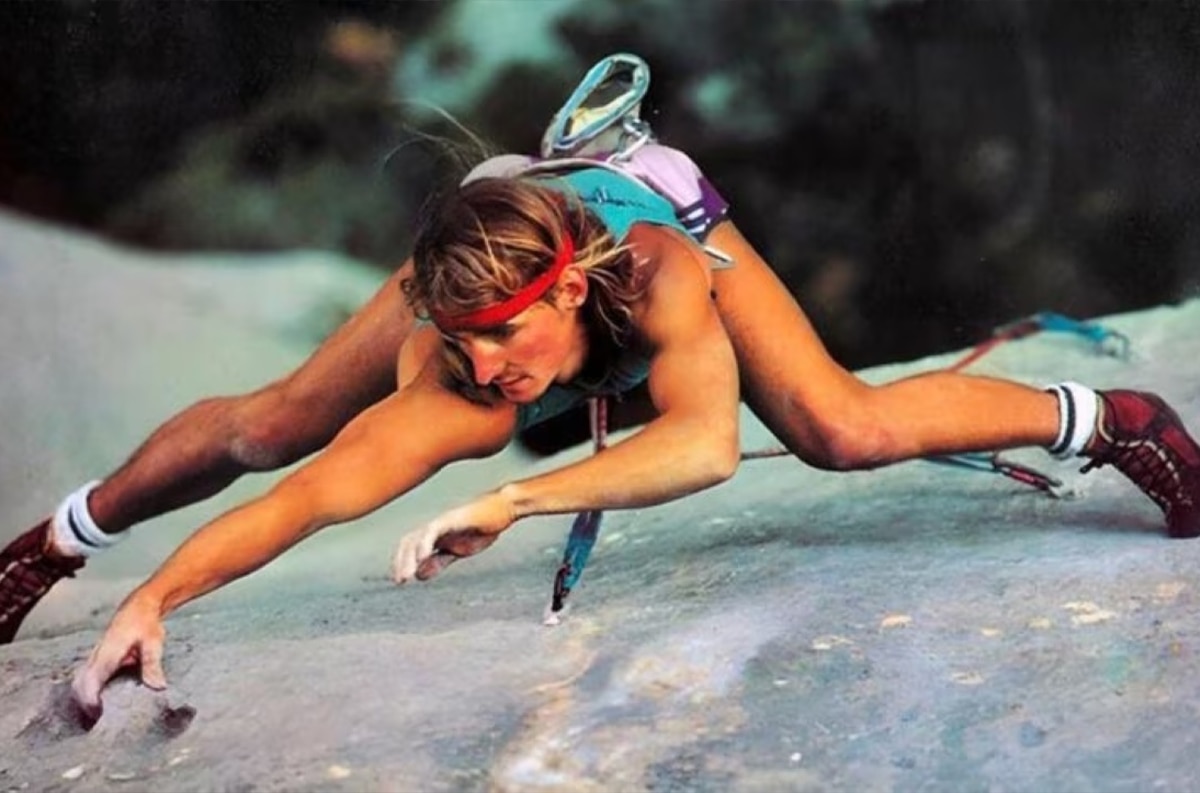

Nello stesso periodo, a Detroit si andava formando la variante della ghettotech, la quale aveva sicuramente delle somiglianze con la sorella di Chicago, ma che, come il nome stesso suggerisce, era fondata da pattern più riconducibili al techno, e cioè elementi più meccanici, oscuri e soprattutto veloci. Queste realtà musicali così vicine, unite alle loro corrispettive manifestazioni “fisiche” (in poche parole: il ballo) causano un gran fermento per le città, che sfocia in vere e proprie street battles in cui i ballerini si sfidano a suon di passi e movimenti sempre più frenetici e complessi, che coinvolgevano tanto i piedi come tutto il resto del corpo.

Quando i bpm vengono aumentati e si inizia a giocare con il pattern ritmico sincopato rompendo la tipica cassa dritta del 4×4, si inizia a parlare di juke. Il footwork è una variante del juke, ma spiegare la differenza tra questi due stili è praticamente impossibile. Ci ha provato il co-fondatore della label Ghettophiles, Matt Frederick, che durante un’intervista ha dichiarato:

“Il juke è tutto incentrato sul ballare con qualcuno, mentre il footwork consiste nel ballare contro qualcuno. La gente fa juke con tracce footwork e fa footwork con tracce juke.”

Ma torniamo a noi. Siamo tra la fine degli anni ’90 e inizio del nuovo millennio, il juke sta riscontrando molto successo tra il pubblico e soprattutto sulla dancefloor. Si iniziano a consolidare i primi nomi dei padri fondatori del (sotto)genere: Rp Boo (la cui “Baby Come On” ne è considerata traccia fondatrice), DJ Rashad, DJ Spinn, DJ Clent, DJ Earl e Traxman, sono solo alcuni dei produttori emergenti che sono anche juke dancers, vivendo dunque la nuova scena musicale direttamente sulle loro gambe.

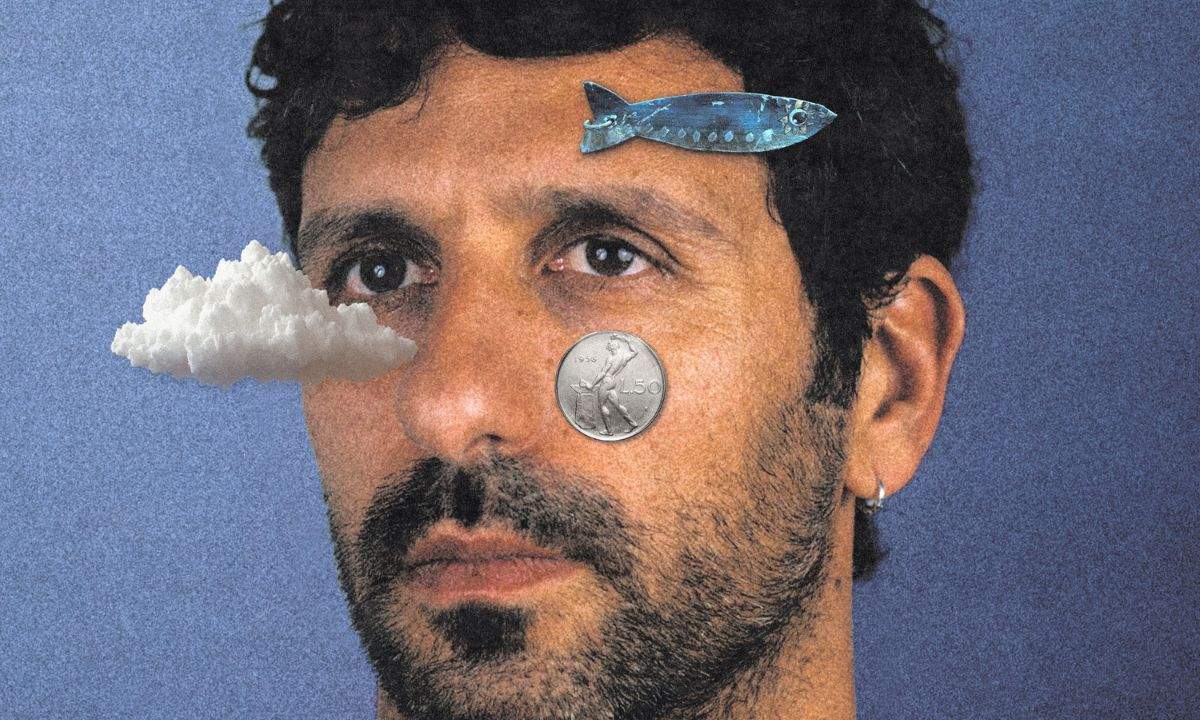

Ma come si passa dal juke al footwork? La risposta arriva con un personaggio emblematico tutt’oggi ancora molto attivo nella scena: RP Boo.

Considerato da molti il Godfather del footwork, RP Boo aveva iniziato a produrre qualcosa di diverso dal juke già negli ultimissimi anni ’90: musicalità più distorta e sperimentale, meno elementi di drum machines e campioni tagliati al massimo livello.

MA QUINDI COS’È IL FOOTWORK?

Dovendo descrivere il footwork oggi, potremmo dire che si basa su alcuni elementi fondamentali: bass kicks, snares, drum kicks, hi hats + uno o più samples – se volete capirne di più, qui trovate una spiegazione molto più concreta da parte di RP Boo stesso. Prodotto tipicamente con una MPC, il footwork è una musica iper-ritmica che gira tipicamente intorno ai 160bpm, basata in gran parte su un modello di campioni (molti samples vengono dal mondo hip hop) estremamente tagliati e manipolati, accompagnati da pattern sincopati, drum machines e potenti linee di basso.

Come abbiamo già detto, il footwork è nato come una battaglia sulla pista da ballo: squadre rivali si sfidavano a ritmi e mosse sempre più veloci e complicate, e i DJ che li accompagnavano si adeguavano a questo crescendo, aumentando sempre di più i battiti per minuto dei loro pezzi. È un incontro fondamentale, perché ballo e Footwork sono strettamente collegati. Uno non può esistere senza l’altro. È un po’ come cercare di capire se sia nato prima l’uovo o la gallina.

Per strada, nelle palestre o nei centri ricreativi, questi incontri hanno avuto per molto tempo – e, in realtà, continuano ad avere – un carattere estremamente underground, relegato alla strada e alla realtà alternativa della grande metropoli.

In un contesto così sotterraneo, dunque, com’è diventato il footwork così conosciuto anche nel resto del mondo?

Nei primi anni 2000 i precursori del nuovo footwork decidono di mettere insieme le forze per far conoscere al mondo esterno quello che stavano facendo. DJ Rashad e DJ Spinn, che condividevano la loro passione già dall’adolescenza, fondano il collettivo “GhettoTeknitianz“, che cambia poi il suo nome in Teklife nel 2011. Il collettivo (che è anche etichetta) è formato tutt’ora dai principali membri e precursori dello stile – Gant Man, DJ Paypal, Rp Boo, DJ Manny per citarne alcuni – anche se il suo co-fondatore DJ Rashad è venuto a mancare prematuramente nel 2014.

I catalizzatori che invece hanno contribuito a far conoscere questo stile anche fuori da Chicago sono sicuramente diversi, ma possiamo limitarci qui a due semplici nomi non di certo sconosciuti tra gli esperti: Planet Mu e Hyperdub.

Corre l’anno 2010 e l’ancora GhettoTeknitianz ottiene il primo vero riconoscimento internazionale da parte della famosa etichetta britannica Planet Mu. La label, infatti, pubblica “Bangs & Works Vol. 1 (A Chicago Footwork Compilation)” attirando l’attenzione del continente europeo su questa musica così peculiare. La compilation riscuote un grande successo e nel 2013 DJ Rashad pubblica il suo primo album di debutto “Double Cup” sull’etichetta britannica di Kode9, Hyperdub, ricevendo ottime critiche. È un momento di svolta, perché da quel momento il footwork inizia a diffondersi e ad essere ascoltato in tutto il mondo.

Dall’Europa, alla Russia e arrivando persino al Giappone, il footwork è tutt’oggi uno stile musicale largamente prodotto e e che nel tempo sta vivendo delle sperimentazioni e commistioni estremamente interessanti.

Nel prossimo episodio vedremo quali. Stay tuned!

ENGLISH VERSION

PARKETT GUIDES: Let’s Talk Footwork (Vol. I)

In an electronic music landscape rich with overlapping subgenres, Parkett has decided to bring some clarity. This new column isn’t about setting rules: the goal is research, dialogue, and open conversation between those who make music and those who listen to it.

PREAMBLE

– Drum and bass?

– We can’t accept drum and bass, we need jungle, I’m afraid.

Quote aside (if you haven’t caught it already, HERE’s the reference), how many times has it happened to you that, while trying to categorize a track—even just mentally—you started doubting its genre, or more often its subgenre or style? Or how many people tend to reduce all electronic music to a simple “Yeah, I like techno”?

The first distinction to make is, of course, between types of listeners. The reality is that there are two main kinds of listeners: those who just listen to a track without really questioning what kind of music it is… and those who do. Every way of listening is personal and unique, and we believe it should be free from any kind of judgment. That said, this column was created with the aim of starting an open dialogue with the second group—the ones who often find themselves hesitating between two or more styles of electronic music when trying to categorize what they’re hearing. And to those who never face such doubts: our sincerest congratulations.

It’s also true that some tracks—and here we’re focusing solely on electronic music—are unclassifiable, or at least hard to pin down into a single category. Still, within all this (wonderful) musical cross-pollination, it’s worth recognizing that tempos, rhythms, and instruments tend to lean more toward certain styles than others. Parkett’s goal is precisely to provide a helpful tool for navigating these distinctions and identifying the key characteristics of each style. This new column isn’t here to lay down the law: the goal is to do some research, ask questions, and why not, spark an open dialogue between those who make music and those who listen to it. So let’s stir the pot if we need to—but let’s make it good trouble. Enjoy the read!

FOOTWORK

This style has enjoyed massive success over the last fifteen years, but it actually began as something deeply underground, confined at first to specific places and small groups of people.

To talk about footwork’s origins, we have to go to Chicago in the 1990s. At that time, the city’s streets were buzzing: house music gave rise to ghetto house, also called booty house in its more energetic variant, with stronger drums and often rap vocals containing explicit sexual content. We’re still talking about 120-130 BPM. Here’s a practical example of what ghetto or booty house sounded like in one of the most emblematic mixtapes of the time, made by DJ Funk, one of the genre’s pioneers:

At the same time, in Detroit, a variation called ghettotech was taking shape. It shared some similarities with Chicago’s scene but, as the name implies, it was rooted in techno patterns, more mechanical, darker, and especially faster. These closely related musical scenes, combined with their physical expressions—namely, dance—sparked major energy in their cities. This led to street battles where dancers competed with increasingly fast and complex steps and movements involving not just feet but the entire body.

When BPMs rise and the rhythmic pattern becomes syncopated, breaking away from the standard 4/4 kick, you start to hear juke. Footwork is a variant of juke, but explaining the difference between the two is nearly impossible. Matt Frederick, co-founder of the label Ghettophiles, put it this way in an interview:

“Juke is all about dancing with someone, while footwork is about dancing against someone. People do juke to footwork tracks and footwork to juke tracks.”

Back to the late ’90s and early 2000s: juke was gaining traction with audiences and especially on the dancefloor. Early pioneers started to emerge: RP Boo (whose Baby Come On is considered a foundational track), DJ Rashad, DJ Spinn, DJ Clent, DJ Earl and Traxman among them. Many of these producers were also juke dancers, experiencing the scene first-hand.

How did we move from juke to footwork? The answer comes from a key figure still active today: RP Boo. Considered by many the Godfather of footwork, he started producing something different from juke in the very late ’90s: more distorted and experimental music, with fewer drum machine elements and heavily chopped samples.

SO, WHAT IS FOOTWORK?

Footwork today can be described by a few fundamental elements: bass kicks, snares, drum kicks, hi-hats, plus one or more samples (for a more concrete explanation, check out RP Boo’s own words here). Typically produced on an MPC, footwork is hyper-rhythmic music around 160 BPM, based largely on samples—many taken from hip hop—cut up and manipulated, paired with syncopated drum patterns, drum machines, and powerful basslines.

Like we said before, footwork was born as a dance battle: rival crews competing with faster and more complex rhythms and moves, and DJs raising the BPM to match the intensity. Dance and footwork are inseparable one can’t exist without the other. It’s like the chicken and egg question.

On the streets, in gyms, or recreation centers, these battles have long—and still—maintained a deeply underground character, confined to the streets and alternative realities of big cities.

So in such an underground scene, how did footwork become known beyond Chicago and gain recognition worldwide?

In the early 2000s, footwork pioneers joined forces to spread their music beyond their scene. DJ Rashad and DJ Spinn, longtime friends, founded the collective GhettoTeknitianz, which was renamed Teklife in 2011. The collective and label still includes key members and pioneers of the style: Gant Man, DJ Paypal, RP Boo and DJ Manny among otherseven though co-founder DJ Rashad passed away prematurely in 2014.

Several catalysts helped bring footwork out of Chicago, but we’ll focus on two key names well known among experts: Planet Mu and Hyperdub.

In 2010, the then GhettoTeknitianz crew earned their first major international recognition with the UK label Planet Mu. The label released “Bangs & Works Vol. 1 (A Chicago Footwork Compilation)“, drawing Europe’s attention to this unique sound. The compilation was a big success. In 2013, DJ Rashad released his debut album “Double Cup” on Kode9’s British label Hyperdub, receiving great reviews. This was a turning point, as footwork began to spread and be heard worldwide.

From Europe to Russia, all the way to Japan, footwork remains a widely produced style that’s continuously evolving through fascinating experiments and genre-blending.

In the next episode, we’ll explore exactly that. Stay tuned!